What is a Movie Review?

A movie review is a critical analysis of a film that evaluates how effectively it uses cinematic techniques to tell its story and create meaning.

The Three Essential Components

1. Analysis of cinematic elements

Mise-en-scène, cinematography, editing, sound, performance the how of filmmaking

2. Evaluation of effectiveness

Whether these elements successfully achieve the film's goals

3. Evidence from the film

Specific scenes, shots, or moments that support your claims

What a Movie Review Is NOT

- NOT a plot summary (though you'll mention key plot points as evidence)

- NOT just your feelings ("I loved it!" or "It was boring")

- NOT a list of everything that happens (scene by scene recap)

- NOT spoiler filled for general audiences (unless specified as spoiler review)

Movie Review IS

- IS analysis of how cinematic techniques create meaning, emotion, and impact

- IS evaluation supported by specific examples from the film

- IS criticism (which means thoughtful analysis, not just finding flaws)

Need a Strong Movie Review Fast?

Let academic professionals help you submit confident, well argued film reviews.

- Film literacy focused analysis

- Clear thesis and structure

- Zero plagiarism assurance

- On time submission promise

Submit work that stands out for the right reasons.

Get Started NowMovie Review vs. Other Film Writing

| Type | Purpose | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Movie Review (Academic) | Analyze cinematic technique | How the film works as cinema |

| Movie Review (Popular) | Recommend/warn audience | Entertainment value + quality |

| Film Analysis Essay | Deep dive into themes | One specific aspect explored deeply |

| Plot Summary | Describe what happens | Story events only |

This guide covers academic movie reviews that demonstrate film literacy, though the principles apply to all types.

If you also want to learn about book reviews, visit our book review guide.

Essential Film Criticism Terminology

To write sophisticated movie reviews, you need the vocabulary of film criticism. These terms allow you to articulate what you're seeing and how it creates meaning.

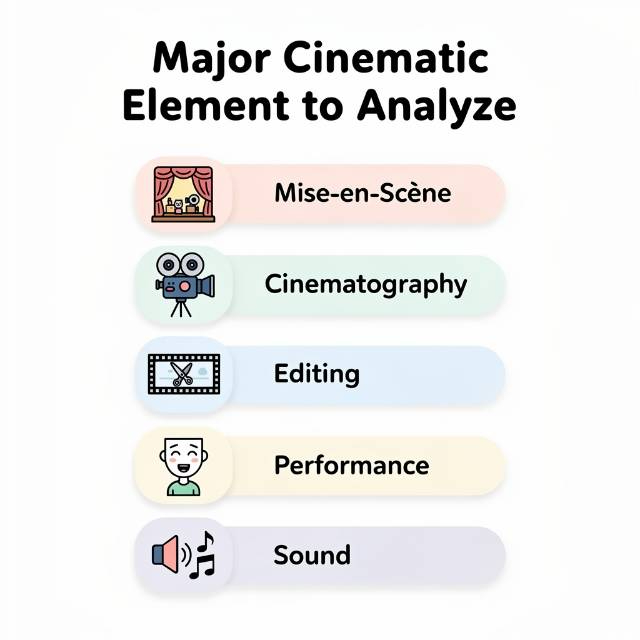

1. Mise-en-Scène (The Foundation)

| Definition: French for “placing on stage” refers to everything that appears within the film frame. Called film criticism's “grand undefined term,” mise-en-scène encompasses: |

a. Setting and Set Design

- Where the scene takes place (location, time period)

- How the environment reflects character or theme

- Real locations vs. constructed sets

Example: The Grand Budapest Hotel uses meticulously constructed sets with symmetrical composition to create a fairy tale aesthetic that matches the film's nostalgic, whimsical tone.

b. Lighting

- High key lighting: Bright, even illumination (comedies, musicals)

- Low key lighting: Heavy shadows, high contrast (noir, horror)

- Natural lighting: Mimics real world light sources

- Emotional impact: Light = hope/clarity; shadow = mystery/danger

Example: Blade Runner 2049 uses perpetually dim, amber tinted lighting to reinforce the dystopian atmosphere and moral ambiguity of its world.

c. Costume and Makeup

- Establishes character identity, social status, era

- Signals character transformation through changes

- Supports genre conventions or subverts them

Example: In Joker, Arthur Fleck's transformation is visualized through his costume evolution from shabby civilian clothes to the iconic purple suit as he embraces his Joker identity.

d. Staging and Blocking

- How actors are positioned within the frame

- Their movement through the space

- Spatial relationships between characters

Example: Marriage Story uses blocking to show emotional distance during arguments, characters are often positioned on opposite sides of the frame with empty space between them.

e. Props

- Objects within the frame that hold meaning

- Can be symbolic or functional to the plot

- Draw viewer attention to important elements

Why mise-en-scène matters: It's how directors visually tell stories without dialogue. Every choice about what appears in the frame communicates meaning.

2. Cinematography (How the Camera Sees)

| Definition: The art of capturing images on film or digital media the technical and aesthetic choices in camera work and lighting. |

Key cinematography elements:

a. Camera Angles

- Low angle shot: Camera looks up makes subject appear powerful, heroic, dominant

- High angle shot: Camera looks down makes subject appear vulnerable, weak, small

- Eye level shot: Creates intimacy, realism, neutral perspective

- Dutch angle (tilted): Creates unease, disorientation, instability

b. Shot Types (Framing)

- Extreme long shot: Establishes location, shows isolation

- Long shot: Full body of character in environment

- Medium shot: Waist up standard for conversations

- Closeup: Face fills frame shows emotion intimately

- Extreme closeup: Eyes, hands, objects emphasizes specific detail

c. Camera Movement

- Pan: Camera rotates horizontally reveals space

- Tilt: Camera rotates vertically reveals height/depth

- Track/Dolly: Camera moves through space follows action

- Handheld: Shaky, immediate creates documentary feel or chaos

- Steadicam: Smooth movement glides through scenes

d. Depth of Field

- Deep focus: Everything in frame is sharp allows layered composition

- Shallow focus: Foreground sharp, background blurred isolates subject

e. Color Palette

- Warm colors (reds, oranges) = passion, danger, energy

- Cool colors (blues, greens) = calm, sadness, detachment

- Desaturated/muted = realism, bleakness

- Vibrant/saturated = heightened reality, fantasy

Example analysis: Mad Max: Fury Road uses predominantly warm desert tones (oranges, yellows) contrasted with the cool blues of the night chase, creating visual variety while the color temperature reinforces the hellish wasteland environment.

3. Editing (How Shots Connect)

| Definition: The selection and arrangement of shots to create sequences, control pacing, and generate meaning through juxtaposition. |

Key editing concepts:

a. Continuity Editing

- Seamless narrative flow

- Matches on action, eyeline, and screen direction

- Makes cuts “invisible”

- Standard for mainstream cinema

b. Montage

- Series of short shots edited together

- Compresses time (training montage)

- Shows thematic connections

- Creates emotional impact through juxtaposition

c. Cut Types

- Cut: Standard transition between shots

- Fade: Gradual transition to/from black signals time passage

- Dissolve: One image gradually replaces another dreamlike, memory

- Jump cut: Jarring cut that breaks continuity creates energy or disorientation

d. Pacing

- Fast editing: Quick cuts create energy, tension, chaos

- Slow editing: Long takes create contemplation, realism, calm

Example: Dunkirk uses rapid cross cutting between three timelines with escalating tension, while Christopher Nolan varies editing pace slow during the grounded tension of waiting on the beach, frenetic during aerial dogfights.

4. Performance (Actors’ Portrayal)

| Definition: The way actors use voice, body, and expression to bring characters to life and convey emotion, personality, or transformation. |

Key Elements:

- Naturalistic vs. Theatrical: Is the acting realistic or stylized for effect?

- Body Language & Facial Expression: Gestures, posture, micro-expressions conveying character psychology

- Chemistry: Interaction between actors that enhances believability and emotion

- Alignment with Genre/Tone: Does the performance match the film’s style (comedy, horror, drama)?

- Supporting vs. Lead Roles: How each actor contributes to narrative impact

Example: Tár-Cate Blanchett’s performance uses subtle physical cues to show her character’s control slipping: early scenes feature precise gestures and perfect posture, while later scenes show fidgety movements and slouched shoulders, signaling transformation without relying on dialogue.

5. Sound Design (The Sonic Landscape)

| Definition: All auditory elements including dialogue, music, sound effects, and ambient sound that complement and enhance the visual storytelling. |

Key sound elements:

a. Diegetic Sound

- Exists within the story world

- Characters can hear it

- Examples: dialogue, car engines, radio playing in scene

b. Non Diegetic Sound

- Exists outside story world

- Only audience hears it

- Examples: score, narration, symbolic sound effects

c. Score vs. Soundtrack

- Score: Original music composed for the film

- Soundtrack: Preexisting songs used in film

d. Sound Effects

- Realistic (footsteps, doors) or stylized (exaggerated punches)

- Create atmosphere and emotion

- Enhance action and environment

Example: A Quiet Place uses silence as its primary sound element, making every tiny noise terrifying. The lack of score in tense sequences amplifies diegetic sounds breathing, footsteps, creaking floorboards into sources of extreme tension.

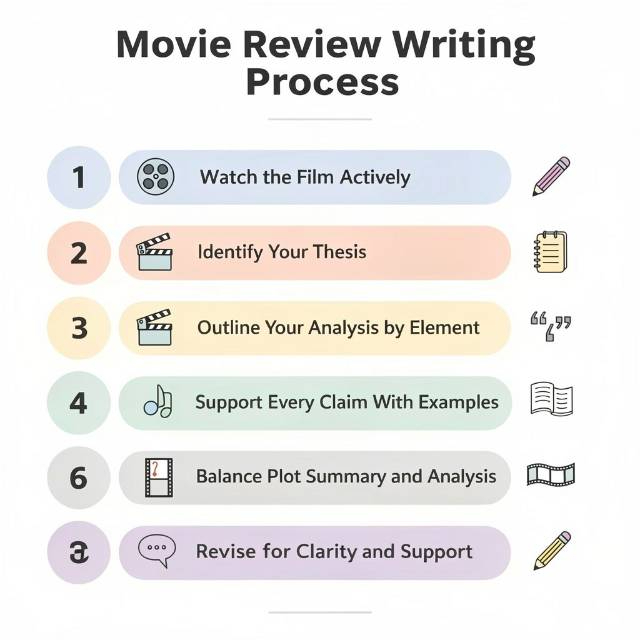

The 7 Step Movie Review Writing Process

Follow this process to transform your viewing experience into sophisticated film criticism:

Step 1: Watch the Film Actively (Take Notes)

Don't just watch analyze while watching.

What to note during viewing:

- Striking visual moments (composition, color, lighting)

- Patterns in cinematography or editing

- Effective or memorable performances

- How sound enhances scenes

- Moments where technique serves story

- Anything that confuses, impresses, or disappoints you

Pro tip: Watch the film twice if possible:

- First viewing: Experience the story, emotional engagement

- Second viewing: Analytical focus on technique

Note taking method:

Keep running notes organized by timestamp:

|

Step 2: Identify Your Thesis (Your Overall Evaluation)

Before writing, determine your central argument your evaluation of the film's success or failure.

Formula:

[Film title] succeeds/fails as [genre] because [main reason related to cinematic technique].

Strong thesis examples:

“Oppenheimer succeeds as both historical drama and character study by using rapid fire montage editing and non linear structure to mirror the fragmented nature of memory and the protagonist's fractured psyche.”

“Transformers: The Last Knight fails as action cinema because its incoherent editing cutting every 1–2 seconds makes spatial relationships impossible to follow, rendering action sequences confusing rather than thrilling.”

Weak thesis examples:

“Oppenheimer is a good movie.” (Too vague)

“I really enjoyed Oppenheimer.” (Personal feeling, not analysis)

“Oppenheimer tells the story of J. Robert Oppenheimer.” (Just plot)

Your thesis should:

|

Step 3: Outline Your Analysis by Element

Organize your review around cinematic elements, not plot summary.

Standard organization:

I. Introduction

Hook (interesting observation about the film)

Basic info (title, director, year, genre)

Thesis statement

II. Story/Narrative (Brief)

One paragraph summarizing premise (not full plot)

Narrative structure (linear, non linear, framed)

III. Mise-en-Scène Analysis

Setting and design choices

Lighting and its effect

Costumes that reveal character

IV. Cinematography Analysis

Camera angles and their meaning

Shot composition

Color palette

V. Editing and Pacing

How scenes connect

Pacing's effect on tension

Use of montage or long takes

VI. Performance Analysis

Lead actor effectiveness

Supporting performances

Chemistry between actors

VII. Sound and Music

Score's emotional impact

Sound design choices

Dialogue delivery

VIII. Conclusion

Restate thesis

Overall evaluation

Recommendation (if applicable)

Note: You don't need separate paragraphs for every element; combine related elements when logical.

Analyze Films Like a Pro, Even on Tight Deadlines

Get expert help transforming film observations into polished academic reviews.

- Proper academic formatting

- Original, quality content

- Cinematic element breakdowns

- Guaranteed deadlines met

Never sacrifice quality for speed again.

Start NowStep 4: Support Every Claim With Specific Examples

Never make unsupported claims.

Weak: “The cinematography is beautiful.”

Strong: “Cinematographer Roger Deakins uses natural light and wide angle lenses to capture the vast, empty landscapes in Blade Runner 2049, emphasizing the protagonist's isolation in the sprawling dystopia.”

Weak: “The editing was confusing.”

Strong: “During the climactic fight scene, the editing cuts every 0.8 seconds on average (compared to the industry standard of 3–4 seconds for action), making it impossible to track character positions or understand who's winning.”

Formula for strong analysis:

- Make a claim: “The film's color palette reinforces its themes.”

- Provide a specific example: “Early scenes use warm, golden tones during family moments.”

- Explain the effect: “which makes the shift to cold blue tones after the tragedy feel emotionally jarring.”

- Connect to larger meaning: “visually representing the protagonist's emotional isolation.”

Step 5: Balance Plot Summary and Analysis

| Rule of thumb: Plot summary should be no more than 15–20% of your review. |

When to summarize plot:

- Brief premise in introduction (2–3 sentences)

- Context for specific scenes you're analyzing

- Major plot points that relate to your thesis

When NOT to summarize plot:

- Detailed scene by scene recap

- Subplots that don't relate to your analysis

- The entire second and third acts

Example balance:

Too much plot:

“First, the protagonist wakes up and has breakfast. Then he goes to work where his boss yells at him. After that, he meets a woman at lunch. Later, he goes home and argues with his wife...”

Appropriate use of plot:

“The film's three act structure follows the protagonist's descent into isolation. Early scenes establish his alienation through mise-en-scène: he's consistently framed alone in wide shots even when surrounded by people, visually communicating his disconnection before any dialogue makes it explicit.”

Step 6: Write in Present Tense Using Film-Specific Language

Always write about films in the present tense (even though you watched it in the past).

Wrong: “The director used low angle shots to make the character look powerful.”

Right: “The director uses low angle shots to make the character look powerful.”

Use specific film terminology:

Generic: “The camera shows closeups of the actor's face.”

Specific: “Extreme closeups of the protagonist's eyes reveal his mounting paranoia without relying on dialogue.”

Vague: “The scene looks dark and scary.”

Precise: “Low key lighting with heavy shadows creates a claustrophobic atmosphere typical of film noir.”

Step 7: Revise for Clarity and Support

Revision checklist:

|

How to Analyze Each Cinematic Element

Here's what to look for when analyzing each major film element:

1. Analyzing Mise-en-Scène

Questions to ask:

Setting/Set Design

Lighting

Costumes

|

Example analysis:

“The Grand Budapest Hotel uses aggressively symmetrical framing and pastel color palettes in its mise-en-scène to create a stylized, artificial aesthetic. This artificiality serves thematic purpose: the film is a nostalgic memory filtered through decades of retrospection, so the unrealistic visual design mirrors how memory idealizes and distorts the past.”

2. Analyzing Cinematography

Questions to ask:

Camera Angles

Shot Composition

Camera Movement

Color

|

Example analysis:

“Cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki uses extremely wide angle lenses and deep focus in The Revenant, keeping both foreground and background sharp. This technique immerses viewers in the harsh wilderness environment we simultaneously see the protagonist's struggle in closeup while never losing sight of the vast, unforgiving landscape that threatens him.”

3. Analyzing Editing

Questions to ask:

|

Example analysis:

“Mad Max: Fury Road uses rapid editing during chase sequences averaging 2 second shot lengths to create kinetic energy and chaos. However, George Miller ensures spatial clarity by maintaining screen direction: pursuers always come from the left, the pursued moves right. This consistency allows the fast cutting to generate excitement without causing confusion about who's where.”

4. Analyzing Performance

Questions to ask:

|

Example analysis:

“Cate Blanchett's performance in Tár uses subtle physical cues to show her character's control slipping: early scenes feature precise, deliberate gestures and perfect posture, while later scenes show increasingly fidgety movements and hunched shoulders as her professional façade crumbles, demonstrating transformation through physicality rather than just dialogue.”

5. Analyzing Sound

Questions to ask:

|

Example analysis:

“Dunkirk uses Hans Zimmer's score as a structural element, not just emotional underscoring. The soundtrack features a ticking watch sound that creates mounting tension throughout the film's three timelines, sonically reinforcing the race against time premise even during visually quiet moments.”

Common Mistakes That Weaken Movie Reviews

Avoid these pitfalls that signal inexperienced film criticism:

Mistake 1: Writing Mostly Plot Summary

The problem: Spending most of the review recapping what happens rather than analyzing how it happens.

Why it fails: Plot summary isn't analysis. Your professor has likely seen the film or can read a synopsis.

Fix: Limit plot to 2-3 sentences in your introduction, then reference specific scenes only as evidence for analytical points.

Mistake 2: Relying on Personal Feelings Without Support

The problem: Stating "I loved it" or "It bored me" without explaining why using cinematic terms.

Why it fails: Personal reactions aren't analysis. Anyone can say they liked or disliked something.

Fix: Transform feelings into analytical claims. "It bored me" becomes "The film's slow pacing with average shot lengths exceeding 45 seconds creates contemplative atmosphere but may challenge viewers expecting conventional thriller pacing."

Mistake 3: Making Vague, Unsupported Claims

The problem: Broad statements without specific examples.

Examples:

- "The acting was great"

- "The cinematography was beautiful"

- "The editing was bad"

Fix: Every claim needs a specific example: "Joaquin Phoenix's performance in Joker uses unsettling physical tics the uncontrollable laughter, hunched posture, jerky movements to externalize the character's psychological fragmentation."

Mistake 4: Ignoring Cinematic Technique

The problem: Discussing only story, themes, and acting while ignoring camerawork, editing, sound, mise-en-scène.

Why it fails: Film is a visual medium. Great film criticism analyzes how stories are told through visual and sonic means.

Fix: Dedicate paragraphs to cinematography, editing, and sound design, not just performances and plot.

Mistake 5: Writing in Past Tense

The problem: "The director used..."

Why it's wrong: Films exist in eternal present they "happen" every time someone watches them.

Fix: "The director uses..."

Mistake 6: Spoiling the Ending (For General Audience Reviews)

The problem: Revealing major plot twists, deaths, or endings for popular/general audience reviews.

When it's okay: Academic analyses, specifically marked "spoiler reviews," reviews of older films

Fix: You can allude to narrative turns ("the third act revelation transforms our understanding of earlier scenes") without explicit spoilers.

Mistake 7: Confusing Opinion With Analysis

Opinion: "This movie is bad."

Analysis: "The film's reliance on exposition heavy dialogue undercuts the visual storytelling, telling audiences information that mise-en-scène and cinematography could have shown."

| The difference: Analysis explains why using film specific concepts. Opinion just states preferences. |

Related Resources

- Analytical Essay Guide (apply analytical skills to film)

- Literary Analysis Guide (similar analytical techniques)

- Critical Analysis Guide (evaluate arguments and evidence)

- Research Paper Guide (for longer film analysis essays)

Struggling to move beyond plot summaries? Our legit essay writing service helps in applying proper film criticism terminology with confidence.

Complete Example of Movie Review

100 Nights of Hero (2025)

Introduction

100 Nights of Hero (dir. Julia Jackman, 2025) is a whimsical fairy tale drama that reimagines medieval romance and myth through a contemporary, feminist lens. Set in a richly detailed fantasy world, the film follows Cherry (Maika Monroe), who must navigate a perilous bet placed by her neglectful husband, and her loyal maid Hero (Emma Corrin), whose bond with Cherry becomes central to the narrative’s emotional heart. This review evaluates how effectively the film uses cinematic elements to create meaning and impact, ultimately arguing that 100 Nights of Hero succeeds as an imaginative, visually lush fable that sometimes falters narratively due to its thin central plot but remains compelling in its themes and performances.

Mise-en-Scène

100 Nights of Hero uses its production design to establish a layered, fairy tale world. Settings range from ornate castles to sweeping desert landscapes, grounding the narrative in a stylized environment that feels simultaneously mythic and lived in. Costumes, designed with intricate fabrics and cultural details, deepen character identities and reinforce the film’s blend of fantasy and folklore. Lighting often leans toward warm natural tones during intimate character moments and cooler palettes in moments of isolation or conflict, visually supporting both narrative mood and thematic shift. These choices contribute to an immersive world that communicates emotional stakes without relying solely on dialogue.

Cinematography

Cinematographer Xenia Patricia crafts 100 Nights of Hero with compositions that balance wide, storybook like frames and intimate closeups. Wide shots emphasize the vastness of the world and the protagonist’s emotional journey, while careful framing and shallow focus isolate characters during pivotal moments of transformation or self reflection. The dominant color palette, rich earth tones contrasted with jewel bright costumes, reinforces the film’s fairy tale aesthetic and symbolic emphasis on inner vitality amid external constraints. These visual strategies anchor the narrative’s emotional texture.

Editing

The editing in 100 Nights of Hero supports its leisurely, fable like pacing. Transitions between scenes favor reflection over urgency, allowing thematic and visual details time to resonate. While this approach creates a rhythmic flow that aligns with the film’s fairy tale tone, it also contributes to uneven narrative momentum in the central plot, by design, poetic rather than plot driven, and sometimes feels thin when sustained over feature length. Nonetheless, the measured editing helps foreground character moments and thematic interplay rather than conventional plot mechanics.

Performance

The performances in 100 Nights of Hero elevate its narrative core. Emma Corrin as Hero brings nuance to a role that balances strength, vulnerability, and wit, while Maika Monroe’s Cherry transitions convincingly from a passive societal role to emerging agency. Their chemistry anchors the film’s exploration of loyalty, identity, and agency, making emotional stakes tangible even when the plot’s momentum slows. Nicholas Galitzine’s portrayal of the seductive Manfred adds an engaging tension that punctuates the central relationship dynamics. These performances ground the film’s thematic ambitions in character authenticity.

Sound Design

The soundscape weaves music, dialogue, and ambient sound to support both setting and emotion. Score selections emphasize the film’s mythic quality without overwhelming visual storytelling, and sound effects from rustling fabrics to environmental atmospherics aid immersion. Occasional moments of relative silence heighten audience attention to character expressions and interactions, reinforcing the narrative’s emphasis on personal struggle and agency over spectacle.

Conclusion

100 Nights of Hero is a visually sumptuous and thematically rich fairy tale that uses cinematic craft to elevate its exploration of loyalty, agency, and storytelling itself. While its narrative can feel thin at times, the film’s mise-en-scène, cinematography, performances, and sound design coalesce to create a compelling viewing experience. By privileging atmosphere and character depth over conventional plot drive, the film demonstrates how cinematic elements can work in concert to communicate meaning beyond mere story events.

100 Nights of Hero is recommended for viewers who appreciate imaginative world building, strong character work, and visual storytelling that resonates on both emotional and symbolic levels.

Write Smarter Movie Reviews Without the Stress

Professional help designed for students who want clarity, depth, and results.

- Structured critical frameworks

- Accurate use of film terminology

- Customized academic support

- 100% original content

Write reviews your instructors recognize as true criticism.

Order NowConclusion: From Viewer to Critic

Writing effective movie reviews transforms how you watch films. Instead of passively consuming stories, you'll actively analyze how cinematography, mise-en-scène, editing, and sound create meaning and emotion.

The essentials:

- Watch actively, taking notes on technique

- Use specific film terminology correctly

- Support every claim with concrete examples

- Analyze how elements create meaning, not just what happens

- Balance brief plot context with indepth analysis

- Write in the present tense

- Connect the technique to the overall evaluation

Remember: Great film criticism explains how movies work as cinema. Anyone can say they liked or disliked a film. Critics explain why, using the language of filmmaking to articulate their evaluation.

Now go watch some films with fresh eyes and write reviews that demonstrate genuine film literacy.