What is an Editorial?

An editorial is an opinion piece published in a newspaper, magazine, or online publication that takes a clear stance on a timely issue and attempts to persuade readers to adopt that viewpoint or take specific action.

The Four Essential Elements

- Timely topic: About current events or pressing ongoing issues, not historical matters

- Clear position: Takes a definitive stand, not "both sides have merit"

- Persuasive purpose: Aims to change minds or inspire action

- Publication voice: Speaks for the publication, not just personal opinion

What Makes a Good Editorial?

Strong editorials share these qualities:

- Urgent relevance: Addresses something happening now that matters

- Definitive stance: Crystal clear where you stand from the start

- Evidence based: Facts, examples, expert opinions support claims

- Action oriented: Often concludes with specific steps readers should take

- Balanced but firm: Acknowledges opposing views but persuasively refutes them

Bad editorial: Good editorial: See the difference? Specific, urgent, actionable, persuasive. |

Why Write Editorials?

- For school: Journalism classes teach editorial writing as core skill

- For publications: School and local papers need opinion pieces

- For advocacy: Editorials influence public opinion and policy

- For change: Effective editorials mobilize communities to action

- For career: Editorial writing teaches persuasion, critical thinking, research

There's no single purpose editorials are foundational to civic discourse.

CONFUSED BY COMPLEX EDITORIAL?

We simplify dense academic texts into clear, engaging editorial.

- Expert interpretation

- Clear conclusions and insights

- Fully original content

- No plagiarism

Submit with confidence.

Order NowEditorial vs Other Writing Types

Editorials share similarities with related forms but have distinct characteristics.

Comparison | Editorial | Other Writing Type | Key Difference |

Editorial vs News Article |

|

|

|

Editorial vs Opinion Column |

|

|

|

Editorial vs Letter to the Editor |

|

|

|

Types of Editorials

Not all editorials serve the same purpose. Knowing the types helps you choose the right approach.

The 5 Main Types

1. Persuasive/Argumentative Editorial

Takes a position on a controversial issue and argues why readers should agree.

- Purpose: Change minds, shift opinion

- Example topic: "Why Our School Should Adopt a Four Day Week"

- Best for: Policy debates, controversial decisions, competing viewpoints

2. Critical/Attack Editorial

Criticizes a policy, decision, or action, explaining what's wrong and why.

- Purpose: Oppose something, expose problems

- Example topic: "The New Dress Code: Unfair, Unequal, Unenforceable"

- Best for: Bad policies, poor decisions, injustices that need calling out

3. Endorsement Editorial

Recommends a candidate, policy, or course of action.

- Purpose: Guide readers toward specific choice

- Example topic: "Why Maria Rodriguez Deserves Your Vote for Student Council President"

- Best for: Elections, funding decisions, major choices facing community

4. Praise/Commendation Editorial

Recognizes achievement, applauds good work, or celebrates success.

- Purpose: Acknowledge positive developments, encourage more

- Example topic: "Kudos to Students Who Organized the Food Drive"

- Best for: Achievements worth recognizing, positive examples to promote

5. Interpretive/Explanatory Editorial

Explains a complex issue and advocates for particular understanding.

- Purpose: Help readers grasp complicated topic, frame issue correctly

- Example topic: "Understanding What the New Graduation Requirements Really Mean"

- Best for: Confusing policies, misunderstood issues, complex situations

Which Type Should You Write?

Consider your situation:

- Controversial decision just made: Critical editorial

- Election approaching: Endorsement editorial

- Complex issue causing confusion: Interpretive editorial

- Positive development to celebrate: Praise editorial

- Debating what should happen: Persuasive editorial

Most common for assignments: Persuasive/argumentative editorials

When in doubt, argue persuasively for a specific position on a current issue.

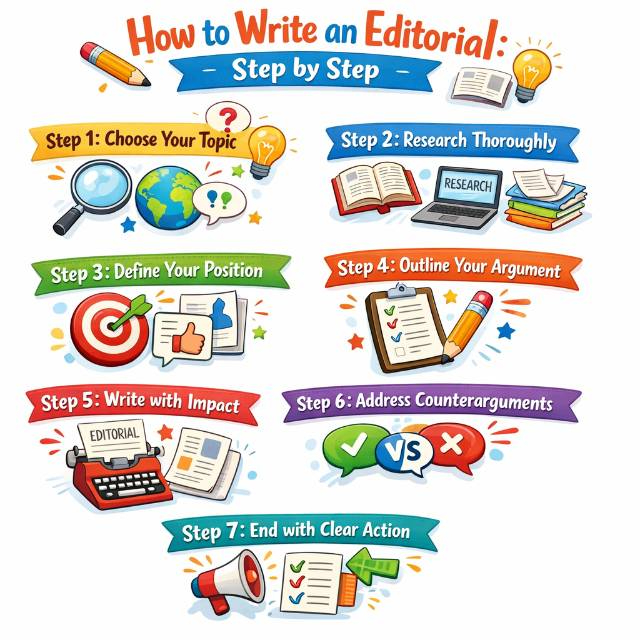

How to Write an Editorial: Step by Step

Follow this 7 step process to craft an effective editorial.

Step 1: Choose Your Topic

Pick an issue that's timely, matters to your audience, and has clear stakes.

Good editorial topics are:

Timely: Happening now or decision pending soon

- School policy changing next month

- Election next week

- Recent controversial decision

- Ongoing problem reaching critical point

Relevant: Affects your readers directly

- School newspaper: student life, campus policies

- Local paper: community issues, city decisions

- National publication: broad impact issues

Debatable: Reasonable people disagree (but you'll argue one side)

Actionable: Readers can do something about it

| Quick topic test: Write: "Should our school ban single use plastic in the cafeteria?" (Timely if being considered, affects students, debatable, actionable) Wrong: "Was the Civil War justified?" (Not timely, no current action possible) |

Step 2: Research Thoroughly

Don't just argue from opinion. Back your position with facts.

What to research:

1. Facts and statistics:

- What's actually happening?

- What are the numbers?

- What does data show?

2. Multiple perspectives:

- What do supporters say?

- What do opponents argue?

- What do experts think?

3. Context and history:

- Has this been tried before?

- What happened then?

- What's the broader picture?

4. Stakeholders:

- Who's affected?

- Who supports/opposes?

- Who has authority to act?

Where to find information:

- School administration (policies, data)

- Local news coverage

- Interviews with affected parties

- Expert sources (teachers, specialists)

- Official documents (board minutes, reports)

Pro tip: Interview people. Direct quotes from students, teachers, officials add credibility and human element.

Step 3: Define Your Position

Before writing, crystallize exactly what you're arguing.

Your position should be:

Specific: Not "phones are good" but "the total phone ban should be replaced with designated phone zones during lunch and between classes"

Actionable: Name who should do what

Defensible: You can back it with evidence

Position statement formula:

[Who] should [specific action] because [main reasons], and [desired outcome].

Example positions:

- "The school board should revise the phone ban to allow structured usage because complete prohibition ignores educational benefits and research from similar districts, while designated phone zones preserve emergency access without classroom disruption."

- "City council must reject the proposed youth curfew because it unfairly restricts law abiding teens, creates enforcement challenges, and addresses symptoms rather than root causes of the problems council members cite."

Step 4: Outline Your Argument

Structure your editorial logically before writing.

Standard Editorial Outline:

I. Introduction (Hook + Position)

Attention grabbing opening

Brief context/background

Clear statement of your position

II. Body: Supporting Arguments

Argument 1 (strongest or most important)

Evidence

Examples

Argument 2

Evidence

Examples

Argument 3

Evidence

Examples

III. Counterarguments & Refutation

Acknowledge opposing view(s)

Explain why they're wrong or insufficient

IV. Conclusion (Call to Action)

Restate position

Specify exactly what should happen

Urge readers to act

Filled Example outline:

Topic: School phone ban

I. Introduction

Hook: Tuesday's board meeting where students weren't allowed to speak

Context: New policy bans all phones 7 AM–3 PM

Position: Ban should be revised to allow structured use

II. Arguments

Educational benefits: Apps enhance learning (cite research)

Safety concerns: Complete ban eliminates emergency contact

Comparable districts: Nearby schools use phone zones successfully

III. Counter + Refute

Counter: "Phones distract from learning"

Refute: Distraction happens regardless; structured use teaches responsibility

IV. Conclusion

Restate: Structured approach better than total ban

Action: Attend Thursday's meeting, demand policy revision

Final punch: "Education means teaching responsible use, not fearful prohibition"

Step 5: Write with Impact

- Opening strategies that work

- Start with a scene

- Lead with a startling fact

- Use a provocative question

- Begin with a quote

Use strong verbs and active voice:

wrong: "The policy was approved by the board"

right: "The board approved the policy"

wrong: "It is believed by many that..."

right "Evidence shows..." or "Experts argue..."

Step 6: Address Counterarguments

Don't ignore the opposition take it on directly.

Effective refutation strategy:

1. State the counterargument fairly

"Phone ban supporters argue that classroom disruption justifies complete prohibition. Board member James Wilson stated, 'We tried partial restrictions and phones remained a distraction.'"

2. Acknowledge any validity

"This concern has merit phone misuse does disrupt learning."

3. Explain why your position is still better

"However, this argument conflates symptom with disease. Disruption stems not from phones themselves but from lack of clear expectations and consequences. Neighboring Central High implemented designated phone zones with strict classroom enforcement disruptions dropped 40% in one semester while preserving legitimate uses. The issue isn't whether phones can distract; it's whether total prohibition works better than structured policy. Evidence suggests otherwise."

Step 7: End with Clear Action

Editorials should mobilize readers, not just inform them.

Strong ending include:

- Specific action steps

- Clear stakeholders

- Sense of urgency

- Memorable final line

NEED A STRONG EDITORIAL FAST?

Our writers specialize in academic analysis across disciplines.

- Graduate and undergraduate level writing

- Clear structure and logical flow

- Accurate referencing

- Deadline safe delivery

You focus on studying. We focus on writing.

Get Started NowEditorial Basic Structure

Editorial Introduction (15-20% of editorial)

Purpose: Hook readers and state your position immediately.

What to include:

- Attention grabbing opening (scene, fact, question, quote)

- Brief context (just enough background)

- Clear position statement (no ambiguity about your stance)

Length: 2-3 paragraphs for 600-800 word editorial

What NOT to do:

- Don't bury your position state it early

- Don't waste space with obvious statements

- Don't begin with dictionary definitions

Editorial Body Paragraphs (50-60% of editorial)

Structure: One argument per paragraph

Each paragraph develops a single reason supporting your position.

Paragraph structure:

- Topic sentence: State your point clearly

- Evidence: Provide specific support

- Explanation: Connect evidence to your argument

- Transition: Lead to next point

How many body paragraphs?

Typically, 3-4 supporting arguments

Choose your strongest points. Editorials are short, so quality beats quantity

Order arguments strategically:

- Start strong (grab attention)

- Build to the strongest (end on the best point)

- OR: Strongest first, then supporting points

Editorial Counterargument Section (15-20% of editorial)

Purpose: Acknowledge and refute opposition

Don't skip this section, it's essential for credibility

Structure:

- State opposing view fairly:

- Acknowledge any validity:

- Refute the argument:

Editorial Conclusion (10-15% of editorial)

Purpose: Drive home your position and mobilize readers

What to include:

- Brief restatement of position (in fresh words)

- Specific action readers should take

- Sense of urgency

- Memorable final line

Length: 1-2 paragraphs

Building Credibility of Editorial

Editorials persuade by combining strong arguments with editorial credibility.

1. Use Concrete Evidence

Every claim needs support:

Wrong: "Most students use phones responsibly."

Right: "According to last month's student survey, 73% of students report using phones primarily for academic purposes during school hours."

Wrong: "Phone bans don't work."

Right: "Districts that implemented total phone bans reported 40% higher confiscation rates but no measurable improvement in test scores, according to data from the State Education Department."

Types of evidence that build credibility:

- Statistics from reliable sources

- Expert testimony from authorities

- Research findings from studies

- Specific examples with details

- Direct quotes from stakeholders

2. Maintain Balanced Tone

Passionate but not hysterical:

Wrong: "This idiotic board clearly hates students and wants to destroy their futures"

Right: "The board's decision, made without student input, ignores both research and the successful models implemented in neighboring districts"

Critical but not personal:

Wrong: "Board member Wilson is obviously clueless about modern education"

Right: "Board member Wilson's claim that 'partial restrictions failed' overlooks that those restrictions lacked enforcement mechanisms a problem policy revision could address"

3. Acknowledge Complexity

Nuance builds credibility:

"The phone disruption problem is real. Teachers shouldn't compete with TikTok for student attention. But complete prohibition addresses this challenge in the least effective way possible."

"Phone ban supporters raise legitimate concerns about distraction. The question isn't whether those concerns exist, it's whether total elimination works better than structured policy. Evidence suggests otherwise."

4. Show You Understand the Issue

Demonstrate you've done homework:

"The board based this decision on 2019 research from suburban Chicago schools context dramatically different from our rural district with dispersed housing, where phones provide crucial emergency contact for students commuting 45+ minutes."

"Three models exist: Central High's designated zones, Westside's classroom by classroom policies, and Eastbrook's time based restrictions. Each reduced disruption while maintaining access. Any would work better than total prohibition."

5. Use Specific Examples

Details are more convincing than generalities:

Wrong: "Students need phones for emergencies"

Right: "Last year, senior Marcus Johnson used his phone to call his diabetic sister's school when she didn't answer texts during her low blood sugar episode. Under the new policy, his phone would have been confiscated, potentially endangering his sister's life."

6. Attribute Sources Properly

Give credit for information:

- "According to Dr. Sarah Chen, Stanford Graduate School of Education: 'Structured technology integration outperforms technology free classrooms by 23% on comprehension assessments.'"

- "The State Education Department's 2024 report on phone policies found..."

- "As board member Martinez noted in Tuesday's meeting..."

7. Avoid Logical Fallacies

Common fallacies that undermine credibility:

- Ad hominem: Attacking person instead of argument

Don't: "Board President Smith is out of touch with reality" - Slippery slope: Claiming one thing inevitably leads to extreme outcome

Don't: "If we allow any phone use, soon students will do nothing but scroll TikTok" - False dilemma: Presenting only two options when more exist

Don't: "Either we ban phones completely or accept total chaos" - Hasty generalization: Broad conclusion from limited evidence

Don't: "One student misused their phone, so obviously all students will"

Common Editorial Mistakes to Avoid

Mistake 1: Burying Your Position

The problem: Readers reach paragraph three and still don't know what you're arguing.

Editorials aren't mystery novels; state your position clearly in the introduction.

The fix: Your stance should be crystal clear by the end of paragraph one, definitely by paragraph two.

Mistake 2: Writing a News Article Instead

The problem: You report facts objectively without taking a position.

That's journalism, not editorial writing.

The fix: Every editorial paragraph should advance your argument. If you're just explaining what happened without arguing what should happen, you're writing news.

Mistake 3: No Evidence

The problem: "The phone ban is bad because I think it's unfair and everyone agrees with me."

Assertions without support don't persuade.

The fix: Back every claim with facts, research, expert opinions, or specific examples.

Mistake 4: Ignoring the Opposition

The problem: You present only your side, never acknowledging contrary views.

Makes you seem unaware or dishonest.

The fix: Dedicate a section to the strongest counterargument and explain why your position is still better.

Mistake 5: Getting Too Personal

The problem: "Board President Smith is an idiot who clearly hates students."

Personal attacks destroy credibility.

The fix: Criticize decisions and policies, not people. Stay professional even when passionate.

Mistake 6: No Clear Action

The problem: Your editorial argues passionately but leaves readers thinking "So... what now?"

The fix: Tell readers exactly what they should do: attend a meeting, contact officials, sign a petition, vote, change behavior.

Mistake 7: Wrong Tone for Audience

The problem: Your school newspaper editorial sounds like a legal brief, or your professional editorial sounds like a text message.

The fix: Match tone to publication and audience while maintaining credibility.

Struggling with research or structure? Our professional essay writing service can polish your editorial for publication.

Editorial Examples

Example 1: School Issue Editorial (Student Newspaper)

Title: Why the Phone Ban Fails Students and Teachers Alike

Tuesday night, 47 students stood along the walls of the school board meeting room not because seats were full, but because the board refused to let students sit or speak during the phone policy discussion. They voted 7-2 for a complete ban anyway, prohibiting all phone use from 7 AM to 3 PM with immediate confiscation for any violation.

This decision fails everyone. The complete ban eliminates legitimate educational use, creates genuine safety concerns, and ignores successful alternatives proven in neighboring districts. The board should immediately revise this policy to allow structured phone use during noninstructional time.

The policy discards legitimate educational tools along with social media distractions. Many teachers successfully integrate educational apps Desmos for math, Quizlet for language practice, Notability for notetaking. Stanford research shows classrooms with structured technology integration outperform technology free environments by 23% on comprehension assessments. Rather than teaching responsible use a skill students need for life the ban takes the easier but less effective path of complete prohibition.

Safety concerns compound educational problems. The policy eliminates all phone access, including medical emergencies. Last year, senior Marcus Johnson used his phone to contact his diabetic sister's school when she didn't respond during a low blood sugar episode. Under the new policy, his phone would have been confiscated, potentially endangering his sister. Emergency situations don't wait for 3 PM.

Successful alternatives exist nearby. Central High implemented designated phone zones during lunch and between classes with strict classroom enforcement disruptions dropped 40% in one semester while preserving emergency access and legitimate uses. Westside Academy gives individual teachers discretion to allow educational phone use in class. Eastbrook High uses time based restrictions. All three report better outcomes than our new total ban.

Phone ban supporters cite classroom disruption as justification. Board member Wilson stated, "We tried partial restrictions and phones remained a constant distraction." This concern has merit misused phones do interrupt learning. However, this logic conflates symptom with disease. Disruption stems not from phones but from absent expectations and consequences. Central High's results prove structured policies work better than prohibition when properly enforced.

The board faces a choice: revise this policy now or defend an ineffective ban while neighboring districts demonstrate better approaches. Parents and students should attend Thursday's follow up meeting at 7 PM in the district office and demand the board table this policy until forming a committee including student representatives to develop evidence based guidelines.

Education should mean teaching responsible technology use, not fearful prohibition. A school that bans phones entirely prepares students for a world that no longer exists.

Example 2: Community Issue Editorial (Local Paper)

Title: Proposed Youth Curfew: Wrong Problem, Wrong Solution

City council will vote Tuesday on a youth curfew requiring everyone under 18 to be off streets by 10 PM on weekdays and midnight on weekends, with exceptions only for employment or supervised activities. Violations would mean mandatory parental contact and possible fines.

This proposed ordinance should be rejected. It restricts law abiding teens, creates enforcement nightmares, and addresses symptoms while ignoring root causes of the problems council members cite as justification.

Council member Rodriguez argues the curfew addresses recent vandalism and late night disturbances. Yet police data shows 73% of juvenile crime occurs between 3-7 PM after school but well before the proposed curfew. The ordinance wouldn't have prevented a single incident cited in council discussions. Law enforcement resources would be better spent on actual problem times, not theoretical late night prevention.

The policy punishes responsible teens for others' actions. Sixteen year old debate team members returning from competitions after 10 PM would face police stops. Students working closing shifts at restaurants would require employer documentation. Teens attending evening concerts or movies perfectly legal activities would need parental escorts. The curfew restricts freedom without corresponding benefit.

Enforcement concerns extend beyond fairness to practicality. The ordinance requires officers to verify ages, contact parents, process paperwork diverting resources from serious issues. Neighboring Springfield implemented a similar curfew in 2020 but repealed it 18 months later when enforcement costs exceeded $180,000 annually while juvenile crime remained unchanged.

Effective alternatives exist. The YMCA's late night teen center, operating until midnight Thursday Saturday, serves 150 teens weekly with zero incidents reported. Expanding programs like this addresses boredom and lack of supervision actual root causes rather than imposing blanket restrictions.

Curfew supporters argue parents support the measure. Some do but the 200-signature petition opposing it, signed by both parents and teens, suggests division rather than consensus. Good policy requires more than "some parents approve."

The underlying concerns about teen safety and community order deserve attention. But knee jerk restrictions aren't solutions they're political theater masquerading as policy. Council should invest in late night programming, increase police presence during actual problem hours (3-7 PM), and address root causes rather than symptoms.

Council members can demonstrate leadership by rejecting this ordinance and directing staff to research evidence based alternatives. Tuesday's meeting begins at 7 PM concerned residents should attend and speak during public comment.

Effective policy requires identifying actual problems and implementing evidence based solutions. The proposed curfew does neither.

Ready to Impress With Your Editorial?

Get a professionally written editorial that meets academic standards

- Structured and well organized

- Critical, not just descriptive

- Professor approved tone

- Complete confidentiality

Just share the requirements. We deliver quality.

Get Started NowConclusion: Key Takeaways

Editorials are persuasive, not just informative.

They express a clear position on a timely issue and aim to influence readers’ thinking or actions.Choose the right type for your purpose.

Persuasive, critical, endorsement, praise, and interpretive editorials each serve different goals pick the one that fits your topic and audience.Research and evidence are essential.

Strong editorials rely on facts, statistics, expert opinions, and real examples not just personal opinion.Structure your argument logically.

A compelling editorial has a clear introduction, well organized body paragraphs, counterargument acknowledgment, and a decisive conclusion with a call to action.Address opposing views respectfully.

Credibility grows when you acknowledge counterarguments and refute them with evidence.Be concise, specific, and action oriented.

Every paragraph should support your position, and your conclusion should tell readers exactly what to do next.Maintain a professional, balanced tone.

Critique policies or decisions, not people, and match your tone to your audience and publication.Editorials empower change.

Whether in school papers, local publications, or broader media, well crafted editorials influence public opinion, spark discussion, and inspire action.

Final Thought:

An effective editorial combines clarity, research, persuasion, and credibility. With these tools, your voice can make a meaningful impact turning opinion into action.