The Role of the Essay Introduction in Academic Writing

First impressions determine if anyone reads further.

Think about how you browse articles online. If the opening doesn't grab you in 10 seconds, you click away.

Professors do the same thing with student essays. Your introduction makes them decide:

- Is this worth reading carefully or just skimming?

- Does this student understand the assignment?

- Will this essay deliver on its promises?

A strong introduction does three critical jobs:

| 1. Hooks attention: Makes readers curious about what comes next |

| 2. Provides context: Gives background readers need to understand your topic |

| 3. Presents your thesis: States your main argument clearly |

When these three elements work together, readers commit to reading your entire essay. When they're missing or weak, readers mentally check out, even if your body paragraphs are brilliant.

The harsh reality: professors often decide your grade within the first paragraph. A compelling introduction signals quality thinking. A generic, boring opening signals that the essay that follows won't be worth their time.

Stuck on the First Paragraph?

Get expert help crafting strong essay introductions

- Engaging hooks that capture attention instantly

- Clear background context that sets up your argument

- Strong thesis statements written by professionals

- Introductions tailored to your essay type and subject

Start your essay with confidence, our essay writing service helps you get past the hardest part.

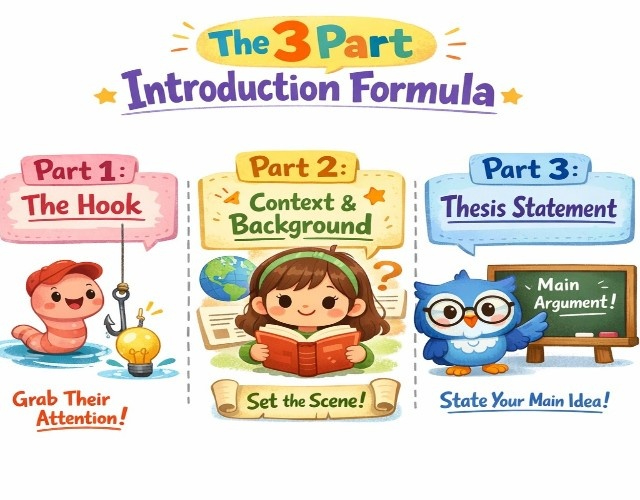

Order NowThe 3 Part Introduction Formula

Every strong essay introduction follows this structure:

Part 1: The Hook (1 to 2 sentences)

Open with something that makes readers curious. Don't ease in with obvious statements; grab attention immediately.

What works

- Surprising statistics

- Provocative questions

- Bold statements

- Relevant anecdotes

- Compelling quotes

Part 2: Context & Background (2 to 4 sentences)

Provide information readers need to understand your topic and why it matters. Don't assume everyone knows what you're discussing.

What to include

- Brief history or background

- Key definitions (only if essential)

- Why this topic matters

- Current relevance

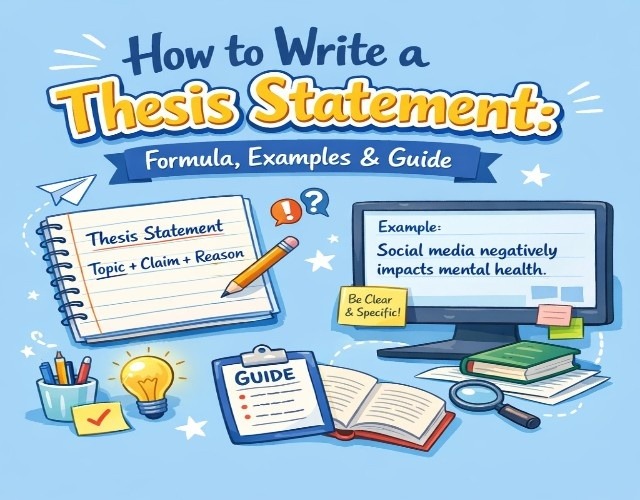

Part 3: Thesis Statement (1 sentence)

State your main argument clearly. This sentence tells readers exactly what your essay will prove or explain.

Requirements

- Takes a clear position

- Previews main points (for longer essays)

- Is specific and arguable

- Connects to everything that follows

Learn more about crafting strong thesis statements in our thesis statement guide.

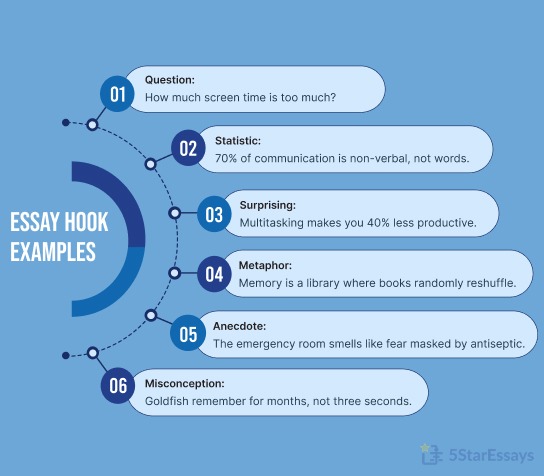

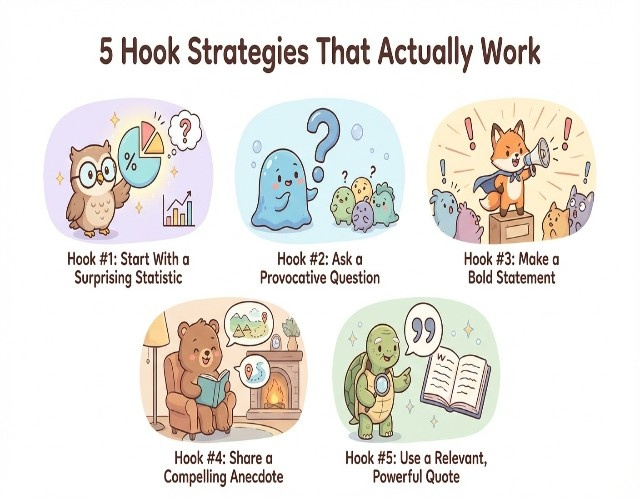

5 Hook Strategies That Actually Work

Hook #1: Start With a Surprising Statistic

Numbers grab attention when they're unexpected or shocking.

Example for a climate change essay:

"By 2050, climate migration could displace 1.2 billion people, more than every war in human history combined. Yet most climate policy focuses on carbon reduction rather than preparing for mass population movement."

Why it works: The specific number is shocking enough to make readers pause. The comparison to wars creates context. The contrast with current policy sets up an argument.

Hook #2: Ask a Provocative Question

Questions make readers think and engage with your topic immediately.

Example for social media essay:

"What if the platform connecting you to friends is actually making you more isolated? For 2.9 billion Facebook users, that paradox defines modern social connection."

Why it works: The question creates cognitive tension; readers want the answer. The specific user number adds credibility. The setup introduces your essay's central argument.

Browse more hook examples across every essay type.

Hook #3: Make a Bold Statement

Confident claims command attention when backed by your essay's argument.

Example for an education essay:

"Traditional lectures are the least effective way to teach complex material, yet 80% of college courses still rely on professors talking at students for 50-minute blocks."

Why it works: The bold opening challenges conventional wisdom. The statistic supports the claim. Readers want to know why lectures don't work and what should replace them.

Hook #4: Share a Compelling Anecdote

Brief, relevant stories make abstract topics concrete and relatable.

Example for healthcare essay:

"Sarah waited three hours in the emergency room with a broken wrist, only to receive a $2,400 bill she couldn't afford. She's insured. Her story represents 45 million Americans facing similar healthcare access crises despite having coverage."

Why it works: The specific story creates empathy. The personal detail makes healthcare policy human. Connecting one story to 45 million shows in scope.

Hook #5: Use a Relevant, Powerful Quote

Quotations from credible sources add authority when they capture key ideas.

Example for technology essay:

"'Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic,' wrote Arthur C. Clarke in 1962. Today, artificial intelligence feels exactly like Clarke's magic, simultaneously miraculous and terrifying, with consequences we struggle to predict."

Why it works: The famous quote establishes credibility. Connecting the 1962 prediction to current AI shows prescience. Sets up a discussion of AI's unpredictable impacts.

Critical rule: Only quote sources your readers will recognize as credible. Don't quote random people or dictionary definitions; these weaken rather than strengthen openings.

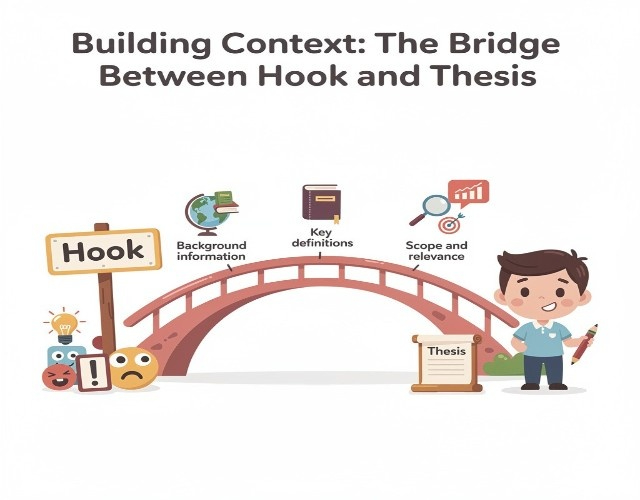

Building Context: The Bridge Between Hook and Thesis

Your hook grabbed attention. Now give readers the information they need to understand your argument.

What Context Should Include:

1. Background information: Brief history, key events, or development of your topic

| Example: "Since Facebook launched in 2004, social media transformed from a college networking tool to a primary news source for 48% of Americans." |

2. Key definitions (only if truly necessary): Define terms your readers might not know

| Example: "Algorithmic curation, the automated selection of content based on user behavior, determines what 2.9 billion users see daily." |

3. Scope and relevance: Why this topic matters and to whom

| Example: "This shift from human-edited news to algorithm-selected content fundamentally changed how democratic societies share information and form consensus." |

4. Current state: Where things stand now, setting up your argument

| Example: "While social media companies claim algorithms simply give users what they want, research reveals these systems actively shape beliefs and behaviors." |

What Context Should NOT Include:

- Obvious information everyone knows ("Since the beginning of time...")

- Dictionary definitions of common words

- Your personal story (unless writing personal/narrative essays

- Information unrelated to your specific argument

Writing Thesis Statements That Drive Your Essay

Your thesis is the most important sentence in your introduction; it states exactly what your essay will prove.

Requirements for Strong Thesis Statements:

1. Takes a clear position

The strong version makes a specific, arguable claim. |

2. Is specific and focused

The strong version specifies exactly what action is needed and why. |

3. Previews main points (for longer essays)

Example: "Mandatory voting would increase political participation through three mechanisms: reducing barriers to access, normalizing civic engagement, and creating incentives for parties to appeal to broader constituencies." This thesis tells readers exactly what the essay will discuss. |

4. Is arguable, not obvious

The arguable version makes a claim someone could reasonably disagree with. |

Find more examples and strategies in our thesis statement guide.

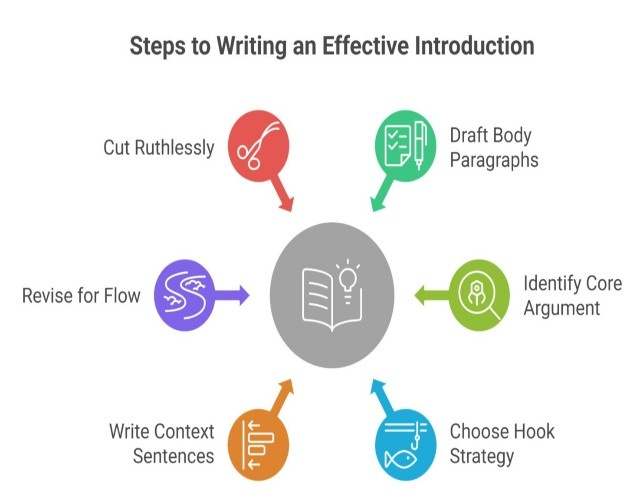

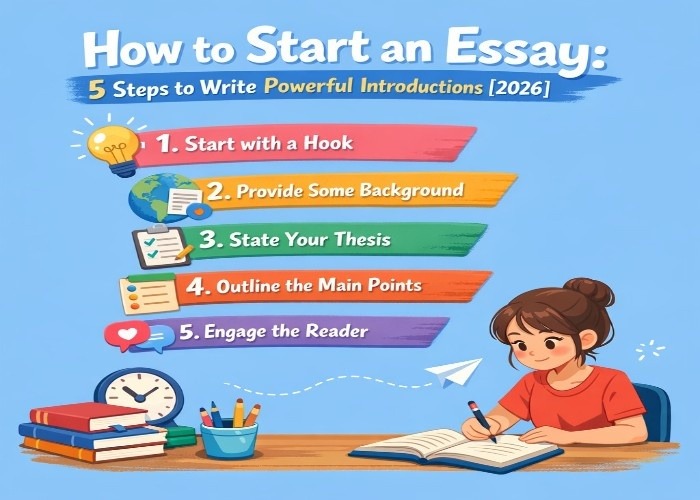

Step by Step: Writing Your Introduction

Follow this process for stronger introductions

Step 1: Draft Your Body Paragraphs First

Write your main arguments before your introduction. You can't effectively introduce ideas you haven't fully developed.

Step 2: Identify Your Core Argument

Review your draft and summarize your main point in one sentence. This becomes your thesis.

Step 3: Choose Your Hook Strategy

Based on your topic and essay type, select the most effective hook approach:

- Statistics work for argumentative essays on policy

- Questions work for philosophical or ethical topics

- Anecdotes work for personal or social issues

- Quotes work for literary analysis or historical topics

Step 4: Write Context Sentences

Add 2 to 4 sentences providing background information readers need. Ask: "What would someone unfamiliar with this topic need to know to understand my argument?"

Step 5: Revise for Flow

Read your introduction aloud. Does each sentence lead naturally to the next? Does your hook connect to your thesis logically?

Step 6: Cut Ruthlessly

Remove any sentences that don't directly serve hook, context, or thesis functions. Introductions should be tight; every word should earn its place.

Start Your Essay the Right Way

Professional support for introductions that impress

- Compelling openings that keep readers engaged

- Thesis driven introductions aligned with grading rubrics

- Academic tone and structure done right

- Help for essays, research papers, and assignments

Don’t let a weak opening hold you back trust our essay writing experts to set the tone.

Order NowThe Complete Introduction Example

Here's how hook + context + thesis work together:

Essay Topic: Should college be free in the United States? Hook (surprising statistic): "Student loan debt in the United States hit $1.7 trillion in 2024, surpassing credit card and auto loan debt combined, a financial burden affecting 43 million Americans." Context (background + relevance): "This crisis stems from college costs that have tripled since 1980 while median wages stagnated. As automation eliminates jobs requiring only high school education, college degrees have become essential for economic mobility. Yet rising costs mean only wealthy families can afford higher education without crippling debt, effectively creating educational barriers based on family income rather than academic merit." Thesis: "The federal government should make public colleges tuition-free because current student debt loads prevent economic mobility, reduce economic growth, and create systemic inequality that contradicts American ideals of equal opportunity."

Why this works:

|

Adapting Your Introduction to Essay Type

1. Argumentative Essays

Focus: State your position clearly and preview your arguments

Example thesis: "The death penalty should be abolished because it fails to deter crime, costs more than life imprisonment, and risks executing innocent people."

2. Analytical Essays

Focus: State what you'll analyze and what insight you'll provide

Example thesis: "Through recurring imagery of birds and flight, Toni Morrison's Song of Solomon explores how individuals balance family obligations with personal freedom."

3. Expository Essays

Focus: State what you'll explain and how you'll organize information

Example thesis: "Urban heat islands form through three interconnected processes: loss of vegetation, heat absorbing building materials, and waste heat from vehicles and HVAC systems."

4. Narrative/Personal Essays

Focus: Set the scene and hint at the significance of your story

Example thesis: "The summer I failed my driver's test three times taught me more about persistence than any success ever had."

If your essay introduction feels weak, a professional essay writing service can help develop engaging hooks and focused thesis statements that meet academic criteria.

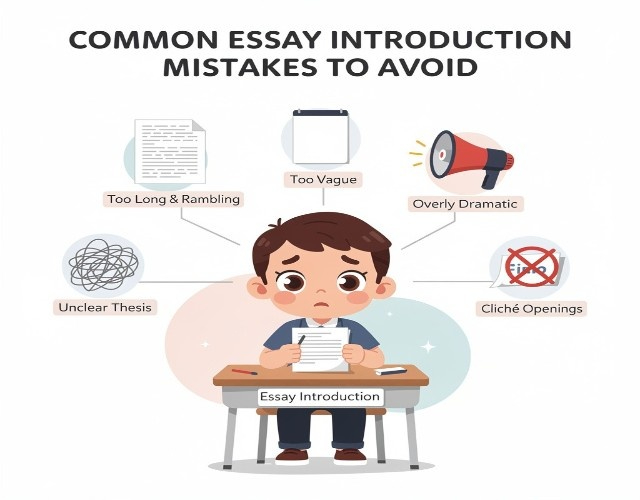

Common Introduction Mistakes to Avoid

Mistake #1: Starting Too Broadly

Bad: "Since the dawn of civilization, humans have sought knowledge."

Why it fails: Vague, clichéd, and doesn't relate specifically to your topic.

Fix: Start with your specific topic immediately.

Mistake #2: Using Dictionary Definitions

Bad: "Merriam-Webster defines 'democracy' as..."

Why it fails: Boring, obvious, wastes space on information readers know.

Fix: Only define terms if they're technical or you're using them in specific ways.

Mistake #3: Announcing Your Intentions

Bad: "In this essay, I will discuss..." or "This paper is about..."

Why it fails: Weak, obvious, wastes words on meta commentary.

Fix: Just state your thesis. The essay format makes your intentions clear.

Mistake #4: Making Your Introduction Too Long

Problem: Introductions exceeding 10% of total essay length.

Fix: For a 1,000 word essay, keep introductions to 100 to 150 words maximum.

Mistake #5: Writing Your Introduction First

Problem: You don't fully understand your argument before drafting body paragraphs.

Fix: Draft body paragraphs first, then write the introduction, knowing exactly what you're introducing. Revise the introduction after completing your draft to ensure it accurately previews your final argument.

Turn Blank Pages Into Powerful Introductions

Expert essay help from the very first sentence

- Creative and academic hooks that fit your topic

- Well structured introductions with clear focus

- Time saving assistance from experienced writers

- Customized support based on your requirements

A strong start leads to a stronger essay, choose our essay writing service and begin with impact.

Order NowBottom Line

Strong essay introductions are a core part of any essay writing guide because they capture attention, set essential context, and present a clear thesis that guides the entire paper.

A simple three part structure, hook, context, thesis, works effectively for all essay types and academic levels.

The hook decides whether readers continue beyond the first sentence. Use engaging techniques such as surprising statistics, thought provoking questions, bold claims, brief anecdotes, or relevant quotes. Skip weak openers like dictionary definitions or vague, overused generalizations.

Context connects your hook to the thesis by giving readers the background they need to understand your argument. Keep it concise, 2 to 4 focused sentences that explain only what’s necessary.

The thesis clearly states what your essay will argue or prove. It should be specific, debatable, and focused. In longer essays, briefly preview your main points. Weak theses state facts; strong ones take a position that invites discussion.

-20154.jpg)