Character Types in Literature

1. Protagonist vs Antagonist

Understanding the difference between protagonist and antagonist is key to analyzing how characters drive the story’s conflict

Protagonist: The main character whose journey drives the narrative. Faces the central conflict. The most significant changes through the story. Protagonists aren't always heroes; they're simply the central figure readers follow. Holden Caulfield is a protagonist despite his cynicism and flaws. Jay Gatsby is a protagonist even as he pursues an impossible dream through questionable means. |

Antagonist: Opposes the protagonist, creating conflict that drives the plot. Antagonists aren't always villains. They can be forces (nature, society), systems (oppressive government), other characters (rival, enemy), or even the protagonist's own nature (internal demons, addiction, fear). In To Kill a Mockingbird, the racist justice system functions as an antagonist more than any single person. |

Analyzing Roles

Ask yourself what each character's function is.

- Does the protagonist change through opposition?

- Do the antagonist exist only to create obstacles, or do they have their own motivations worth examining?

- Strong analysis recognizes that protagonists can have antagonistic qualities, and antagonists often believe they're the hero.

Remember! Writing character analysis helps you understand a character’s traits, motivations, and role in the story.

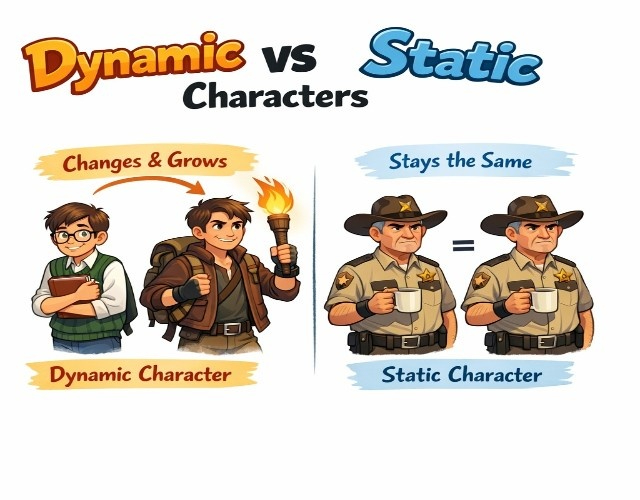

2. Dynamic vs Static Characters

Dynamic Characters: Undergo significant internal change through the story. Their beliefs, values, or personality transform because of events they experience. Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird transforms from an innocent child to someone who understands adult prejudice. Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice changes her judgment about Darcy as she gains new information. |

Static Characters: Remain essentially the same throughout the narrative. Their core personality, beliefs, and values stay constant regardless of events. Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird maintains his moral principles throughout. Sherlock Holmes solves cases but doesn't fundamentally change as a person. Static doesn't mean unimportant; these characters often serve as moral anchors or thematic constants. |

Why It Matters

- Authors choose character types deliberately.

- Dynamic characters show the theme through transformation.

- Static characters demonstrate theme through constancy.

- Analyzing whether a character changes (and why or why not) reveals authorial intention.

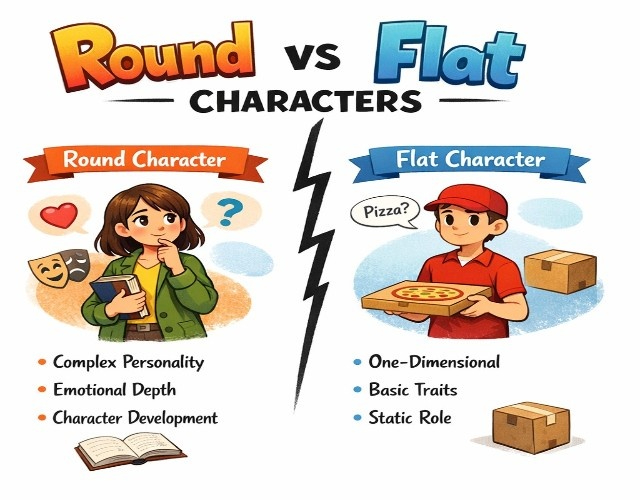

3. Round vs Flat Characters

Round Characters: Complex, multidimensional personalities with contradictions, strengths, and flaws. They feel like real people because they contain psychological depth. Readers understand their motivations even when disagreeing with their choices. Most protagonists are round characters because novels need complexity to sustain reader interest across hundreds of pages. |

Flat Characters: Simple, one-dimensional personalities defined by a single trait or purpose. They serve specific plot functions without psychological complexity. Minor characters are often flat because novels can't develop everyone equally. The shopkeeper who appears for one scene doesn't need full characterization. |

Analysis Approach

- Identify which characters receive psychological depth versus functional simplicity.

- Examine why authors choose to develop certain characters fully while keeping others simple.

- This reveals what (and who) the author considers most important.

Pro Tip: When choosing the best character to analyze, pick one with clear traits, conflicts, and growth throughout the story.

Get Expert Help with Your Essays

Skip the stress. Our professional writers handle everything, so you can submit with confidence.

- 100% original, plagiarism-free content

- Written by degree-holding experts

- On-time delivery, even for tight deadlines

- Unlimited revisions until you're satisfied

No AI. Just real writers, real results.

Order NowMethods Authors Use to Reveal Character

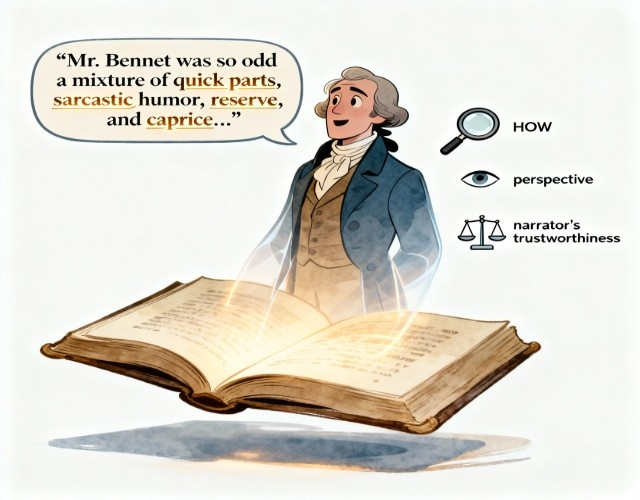

1. Direct Characterization

Definition: The Author explicitly tells readers about character traits through the narrator's description or other characters' assessments.

Example: "Mr. Bennet was so odd a mixture of quick parts, sarcastic humor, reserve, and caprice..." (Pride and Prejudice)

Analysis Approach: Notice HOW the author describes the character. What specific words appear? Whose perspective provides the description? Can the narrator be trusted? Direct characterization tells you what the author wants you to know immediately.

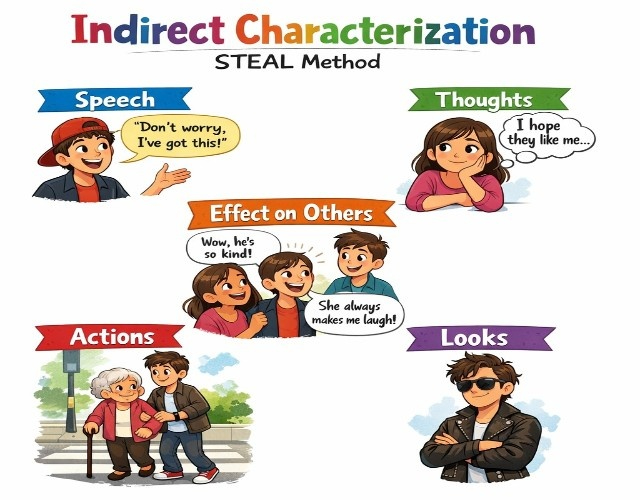

2. Indirect Characterization (STEAL Method)

Speech

- What characters say reveals personality, education, values, and social class.

- Analyze dialogue patterns: Does the character speak formally or casually?

- Honestly or deceptively?

- Notice repeated phrases, verbal tics, or distinctive speech patterns.

Thoughts

- Internal monologue shows motivations, fears, desires, and reasoning.

- First-person narrators and third-person limited perspectives provide direct access to thoughts.

- Analyze what characters think versus what they say; contradictions reveal complexity.

Effect on Others

- How other characters react to this character reveals their social position, reputation, and impact.

- If everyone fears a character, that tells you something.

- If everyone trusts them, that tells you something else.

Actions

- What characters DO reveal values more reliably than what they say.

- Analyze the choices characters make under pressure.

- Actions demonstrate priorities; what characters sacrifice for, fight for, or run from shows who they truly are.

Looks

- Physical description can reinforce character traits or create ironic contrasts.

- Beautiful villains subvert expectations.

- Shabby clothing might indicate poverty or disregard for appearances.

- Analyze whether physical traits function symbolically.

Analyzing Revelation Methods

Strong character analysis examines: HOW authors reveal characters, not just WHAT we learn.

Ask yourself

- Why does the author show this trait through action versus stating it directly?

- Why does this character reveal true feelings through actions contradicting their words?

- These choices create meaning.

Analyzing Character Development

Effective character development helps readers understand a character’s motivations and decisions.

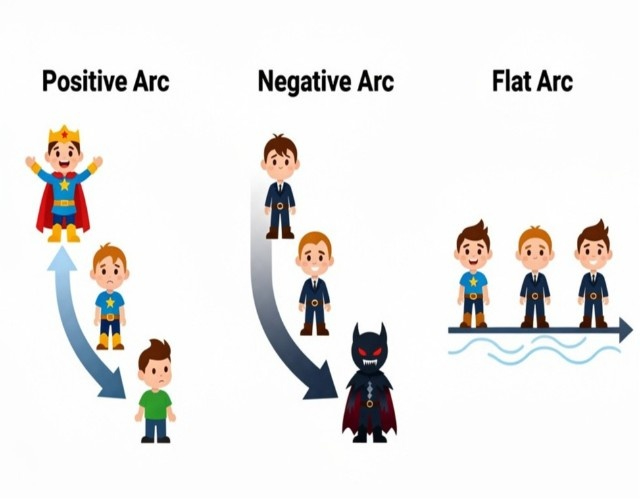

1. Tracking Character Arcs

- Positive Arc: Character grows, improves, and overcomes flaws. Scrooge in A Christmas Carol transforms from miser to generous benefactor. Elizabeth Bennet overcomes prejudice to see clearly.

- Negative Arc: Character deteriorates, succumbs to flaws, or faces corruption. Macbeth descends from honored soldier to murderous tyrant. Jay Gatsby's obsession destroys him.

- Flat Arc: Character stays constant while changing the world around them. Atticus Finch maintains principles while influencing Scout and Jem. Katniss Everdeen in the early Hunger Games doesn't change much internally, but forces external change.

Analysis Method: Map character state at story beginning versus end. Identify the catalyst triggering change (or preventing it). Examine whether change is earned through experience or feels imposed by plot necessity. Analyze WHAT changes (beliefs, values, fears, desires) and WHY.

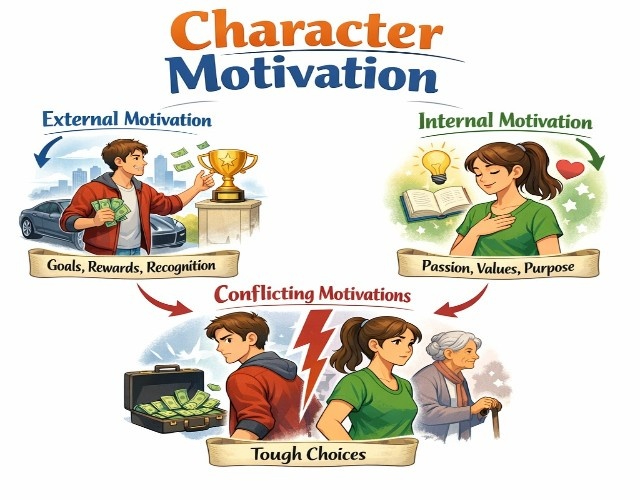

2. Character Motivation

- External Motivation: Concrete goals characters pursue: wealth, power, love, survival, revenge, justice. These drive plot action. Gatsby wants Daisy. Hamlet seeks revenge. Elizabeth Bennet wants respect and security.

- Internal Motivation: Psychological needs underlying external goals: belonging, validation, redemption, control, freedom. These create emotional resonance. Gatsby wants Daisy because she represents acceptance into the class that rejected him. Hamlet seeks revenge because his father's death destroyed his worldview.

- Conflicting Motivations: Complex characters have competing desires, creating internal conflict. Hamlet wants revenge but fears damnation. Romeo loves Juliet but values family honor. These contradictions make characters feel real.

Analysis Approach: Identify both surface goals (what character says they want) and underlying needs (what they actually need). Examine whether motivations change through the story. Analyze moments where motivations conflict; these reveal character complexity.

Character Relationships

1. Foil Characters

Definition: Characters whose contrasting traits highlight each other's characteristics. Authors create foils to emphasize specific qualities through comparison.

Examples:

|

Analysis Method: Identify specific traits that contrast between characters. Examine why the author pairs them. What does the contrast reveal about each character? How does the foil relationship develop the theme?

2. Relationship Dynamics

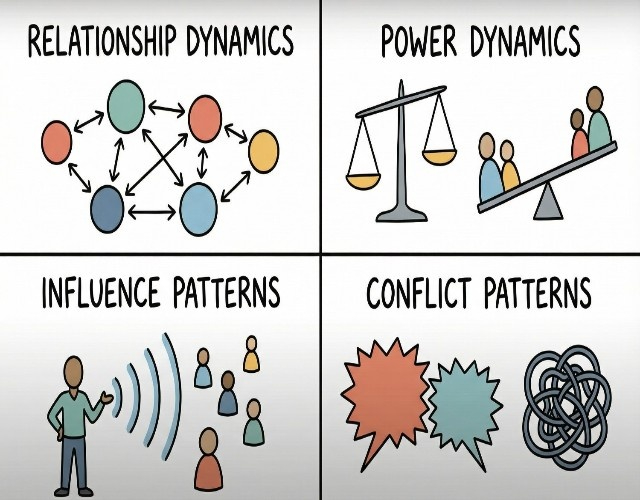

Power Dynamics

- Who holds power in each relationship?

- How does power shift?

- Analyze class, gender, age, knowledge, or emotional leverage, creating an imbalance.

Influence Patterns

- Who changes whom?

- Track how characters influence each other's development.

- Lady Macbeth influences Macbeth's ambition.

- Friar Lawrence influences Romeo and Juliet's choices (with tragic results).

Conflict Patterns

- What creates tension between characters?

- Surface conflicts (arguments, competition) versus underlying conflicts (incompatible values, jealousy, misunderstanding).

Analysis Approach

- Map relationships visually.

- Chart who influences whom.

- Identify power dynamics and how they shift.

- Examine whether relationships change characters or reveal existing traits.

Better Essays. Better Grades. Less Stress.

Our professional writers have helped thousands of students succeed: you're next.

- Original work with zero plagiarism

- PhD literature specialists analyze character psychology

- Deep interpretation of development and motivation

- Delivered on time with free revisions

Trusted. Confidential. 100% human-written.

Order NowCharacter Function in Theme Development

1. Symbolic Characters

Some characters function symbolically, representing abstract concepts beyond their individual identity:

- Gatsby: Represents the American Dream's corruption, pursuing wealth to recreate the past, believing money buys everything, and ultimately destroyed by his illusions.

- Boo Radley: Symbolizes prejudice's victims, feared and misunderstood because he's different, ultimately revealed as a protector rather than a monster.

- Winston Smith: Embodies individual resistance against totalitarianism; his defeat demonstrates the Party's total control.

| Analysis Method: Identify what abstract concept the character represents. Examine how their fate comments on that concept. Analyze whether the character maintains individuality while functioning symbolically. |

2. Character as Thematic Vehicle

Authors develop themes through character choices, development, and consequences:

| Theme 1: Ambition's dangers: Macbeth's ambition leads to paranoia, murder, and destruction. |

| Theme 2: Prejudice's blindness: Scout's education reveals how prejudice distorts perception. |

| Theme 3: Love versus social pressure: Romeo and Juliet's relationship cannot survive family hatred. |

Analysis Approach: Identify the theme connected to your character. Examine how character development, choices, or fate demonstrate that theme. Analyze whether the character's arc proves, challenges, or complicates the theme.

Want to see these techniques in action? Review our literary analysis essay examples with annotated character studies.

Key Techniques for Writing a Character Analysis Essay

1. Close Reading Dialogue

Analyze specific word choices, speech patterns, and communication styles:

| Language Choice | Contrast or Feature | What It Reveals About the Speaker |

|---|---|---|

| Formality | Formal vs. informal language | Education level, social class, and comfort within the relationship |

| Honesty | Honest vs. deceptive speech | Trustworthiness, desperation, or selfprotective behavior |

| Emotional Control | Emotional vs. controlled expression | Personality type, stress response, and cultural background |

| Repetition | Use of repetitive phrases | Obsessions, core values, or psychological state |

2. Tracking Physical Descriptions

Notice when and how authors describe characters physically:

| Type of Description | Purpose | What It Reveals or Achieves |

|---|---|---|

| Initial description | Sets expectations | Establishes social class, attractiveness, or cultural beauty standards |

| Changed description | Shows development or transformation | Reflects a character’s internal state or moral/psychological change (e.g., Dorian Gray’s portrait) |

| Repeated details | Creates symbolism | Signals deeper meaning or thematic importance (e.g., Gatsby’s pink suit, Hester’s scarlet letter) |

| Absence of description | Maintains ambiguity | Suggests a deliberate authorial choice to keep the character open to interpretation |

3. Analyzing Character Names

Authors choose names deliberately:

| Type of Name Use | Description | Literary Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Symbolic names | Names that carry literal or figurative meaning | Reinforce themes or character traits (e.g., Goodman Brown, Mr. Gradgrind, Fortunato, whose “fortune” runs out) |

| Ironic names | Noble or positive-sounding names given to flawed characters | Highlight hypocrisy, contrast appearance vs. reality |

| Cultural significance | Names tied to heritage or social context | Reflect family expectations, cultural identity, or societal pressure |

| Name changes | Alterations in how a character is named or addressed | Signal character development or shifts in identity (e.g., Edna Pontellier, Celie) |

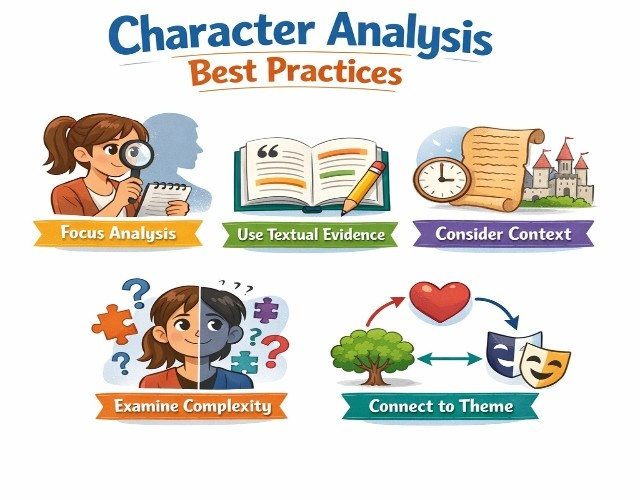

Character Analysis Best Practices

Focus Analysis: Don't try analyzing every trait. Choose 2-3 significant characteristics with substantial textual support. Depth beats breadth.

Use Textual Evidence: Support every claim about character with quotations or specific scenes. Analyze what the evidence reveals rather than just inserting it.

Consider Context: Historical period, social class, and cultural norms affect how readers interpret characters. Victorian heroines face different constraints than modern ones.

Examine Complexity: Strong characters contain contradictions. Analyze how traits conflict (brave but reckless, loving but possessive). Contradictions create realism.

Connect to Theme: Every character analysis should link to a larger meaning. What does this character reveal about human nature, society, or the author's message?

Struggling to track complex character relationships and development patterns? Our reliable essay writing service experts map character arcs, identify motivation layers, and examine relationship dynamics, with custom analysis for any text.

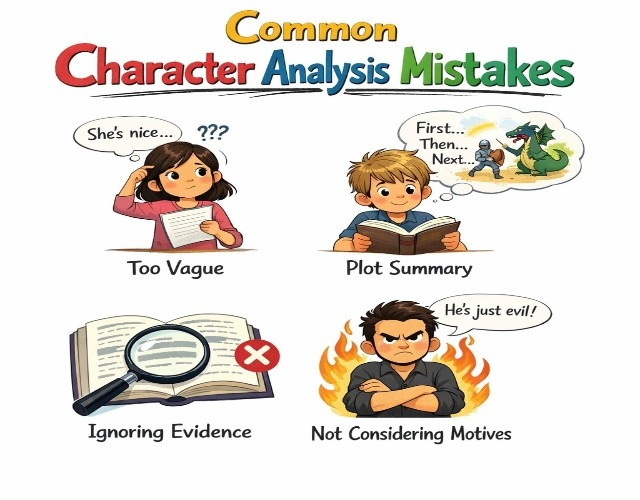

Common Character Analysis Mistakes

Mistake 1: Treating Characters Like Real People: Characters are constructions serving narrative purposes. Don't speculate about the backstory the author didn't provide. Analyze what's on the page.

| Fix: Focus on authorial choices. Ask "Why did the author reveal this trait here?" not "What was the character thinking?" |

Mistake 2: Ignoring Character Type: Analyzing flat characters as if they should be round. Expecting static characters to change.

| Fix: Identify character type first. Analyze whether the character fulfills their intended function rather than expecting every character to be complex. |

Mistake 3: Missing Development Patterns: Only analyzing the character at the story's end, ignoring the journey.

| Fix: Track the character at the beginning, turning points, and end. Map what triggers changes. |

Mistake 4: Plot Summary Instead of Analysis: Describing what the character does without explaining what it means.

| Fix: After stating an action, analyze WHY the character chose it and WHAT it reveals about their personality, values, or development. |

NEED EXPERT CHARACTER ANALYSIS?

Smart students outsource. Our writers deliver higher-quality work in less time.

- Research, writing, and formatting, all done for you

- 24/7 support and direct writer communication

- Plagiarism-free guarantee on every paper

- On-time delivery or your money back

Zero AI. Zero stress. Just results.

Order NowBottom Line

Character analysis reveals how authors create meaning through fictional people who drive narratives and embody themes. By following a literary analysis essay guide and understanding character types (protagonist, antagonist, dynamic, static, round, flat), revelation methods (direct and indirect characterization), and analytical techniques (tracking development, examining motivation, analyzing relationships), you move beyond simply describing characters to interpreting their construction and significance.

Strong character analysis combines close reading of textual evidence with an understanding of characterization techniques, analyzing not just who characters are, but how authors build them and why they matter to the text’s larger meaning.

-19577.jpg)