Literary Analysis Examples by Level

High School Literary Analysis Examples

Example #1: "How To Kill a Mockingbird" Scout's Narrative Voice (Theme Analysis)

Level: High School (Grades 9 and 10)

Length: 642 words

The Mockingbird as Symbol of Innocence Destroyed

Harper Lee's title, To Kill a Mockingbird, references Atticus's warning that "it's a sin to kill a mockingbird" because "they don't do one thing but sing their hearts out for us" (Lee 119). This moral pronouncement becomes the novel's central symbol for innocence harmed by societal cruelty. Tom Robinson and Boo Radley are both "mockingbirds", they harm no one, yet both become victims of Maycomb's prejudice. Through this symbol, Lee argues that maintaining moral courage requires protecting the vulnerable, even when society sanctions their destruction.

Tom Robinson embodies the mockingbird most directly. He helps Mayella Ewell out of pity, asking for nothing in return, yet is accused of rape when Mayella's father discovers her attempt to kiss Tom. During the trial, Atticus proves Tom's innocence beyond reasonable doubt, yet the all-white jury convicts him anyway. Tom's subsequent death, shot while "trying to escape", is presented as inevitable: "Seventeen bullet holes in him. They didn't have to shoot him that much" (Lee 315). The excessive violence reveals that Tom was never going to survive encountering Maycomb's justice system. He sang his heart out through kindness to Mayella, and society killed him for it.

Boo Radley represents a different kind of mockingbird, one caged by social fear rather than prejudice. The neighborhood transforms Boo into a monster through gossip and imagination, but Scout discovers he's been silently protecting her and Jem throughout the novel. When Boo saves the children from Bob Ewell's attack, Sheriff Tate decides to report that Ewell "fell on his knife" rather than expose Boo to public attention (Lee 369). Tate explains: "Taking the one man who's done you and this town a great service an' draggin' him with his shy ways into the limelight, to me, that's a sin" (Lee 370). Tate's language echoes Atticus's earlier pronouncement, exposing Boo would be like killing a mockingbird. Boo's innocence is different from Tom's, but both deserve protection they cannot obtain themselves.

Through the mockingbird symbol, Lee distinguishes between legal justice and moral justice. Tom receives a legal trial but not justice, while Boo receives protection outside the law. Scout's final realization, "It'd be sort of like shootin' a mockingbird", shows she understands that real morality sometimes requires bending rules to protect innocence (Lee 370). This is why Atticus, despite being Maycomb's moral center, doesn't object to Sheriff Tate's decision to lie about Boo's involvement. Atticus's rigid adherence to the law failed to save Tom; Tate's willingness to circumvent it saves Boo.

Lee's mockingbird symbol reveals that innocence is powerless against institutionalized cruelty. Mockingbirds cannot defend themselves; they require protectors willing to take moral stands. Tom had Atticus, but Atticus's courage couldn't overcome a prejudiced jury. Boo has Sheriff Tate, whose protection succeeds only because he works outside the system that destroyed Tom. The novel suggests that moral courage isn't enough when the system itself is immoral, sometimes justice requires those in power to sabotage the machinery of injustice.

What Makes This Work:

- Symbol Analysis:

The essay traces how the mockingbird symbol develops throughout the novel and applies to multiple characters. - Comparative Analysis:

By comparing Tom and Boo as two types of "mockingbirds," the essay shows sophistication in handling symbolism. - Thematic Argument:

The essay doesn't just identify the theme ("innocence"); it makes an argument about what Lee suggests regarding moral courage and justice.

| Remember! A clear Symbolism focused example can make literary analysis easier by showing how objects represent abstract ideas. |

Deadlines Don't Wait. Neither Do We

Urgent deadline? No problem. Our writers work around the clock to deliver polished, plagiarism-free essays

- Custom-written from scratch for every order

- Matched with a writer in your subject area

- Delivered on time, every time

- Full confidentiality guarantee

100% human-written. Satisfaction guaranteed.

Order NowExample #2: "The Great Gatsby" American Dream Critique: Drama analysis example

Level: High School (Grade 11 & 12) / AP Literature

Length: 520 words

The Green Light: Fitzgerald's Symbol of Unattainable Dreams

The American Dream promises that hard work leads to success, but F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby challenges this narrative through the symbol of the green light. While Gatsby dedicates his life to wealth and status, believing they will win Daisy's love, the green light across the bay represents a dream that remains forever out of reach. Through this recurring symbol, Fitzgerald suggests that the American Dream is built on illusion rather than achievable reality, leaving those who pursue it perpetually unsatisfied.

The green light first appears when Gatsby literally reaches toward it, establishing it as a symbol of longing. Nick observes Gatsby "stretched out his arms toward the dark water in a curious way... I could have sworn he was trembling" (Fitzgerald 25-26). The physical distance between Gatsby and the light mirrors the emotional and social distance between him and Daisy. His trembling reveals vulnerability beneath his confident exterior, he knows the dream is distant, yet he cannot stop reaching for it. By placing the light across water, Fitzgerald emphasizes its inaccessibility; Gatsby can see it but never touch it, just as he can glimpse the life he wants but never truly possess it.

As the novel progresses, the green light transforms from a specific symbol of Daisy to a broader representation of the American Dream. Gatsby's pursuit of wealth is motivated entirely by his desire to recapture the past with Daisy, yet Nick realizes that "Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us" (Fitzgerald 180). The word "recedes" is crucial, the dream doesn't disappear, but it moves further away with each attempt to reach it. This captures the essential tragedy of the American Dream: the promise of upward mobility keeps people striving, but systemic inequality ensures most will never achieve it. Gatsby's wealth cannot buy him into old money society, just as the green light remains perpetually across the bay.

The final mention of the green light occurs after Gatsby's death, expanding its meaning beyond one man's failure. Nick reflects that "Gatsby believed in the green light... It eluded us then, but that's no matter, tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther" (Fitzgerald 180). The shift from "him" to "us" universalizes Gatsby's experience, we are all chasing green lights that move further away as we approach. Fitzgerald's use of future tense ("we will run") suggests this cycle continues endlessly. The American Dream perpetuates itself not through fulfillment but through perpetual pursuit.

Fitzgerald's green light symbolizes the seductive and ultimately empty nature of the American Dream. Gatsby's wealth, parties, and mansion are all tools to reach the green light, yet they bring him no closer to genuine happiness or belonging. The light's persistence across the bay throughout the novel, never dimming, never reachable, reflects how the promise of the American Dream endures despite countless individual failures to achieve it. In creating a symbol that is simultaneously visible and unattainable, Fitzgerald captures the tragic core of a national mythology: the dream that drives us is the same dream that destroys us.

What Makes This Work:

- Strong Thesis:

The thesis goes beyond plot summary ("The novel is about the American Dream") to make an argumentative claim about how Fitzgerald uses the green light symbol to critique the American Dream. - Textual Evidence:

Every body paragraph includes direct quotes from the text, with page citations. The evidence is specific, not just "Gatsby reaches for the light" but the exact moment with context. - Close Reading:

Notice how the essay analyzes specific word choices: "recedes," "trembling," "orgastic future." Close reading of language shows deep engagement with the text. - Connects to Larger Themes:

The essay moves from analyzing the symbol itself to explaining what it reveals about the American Dream more broadly. This is the "So what?" of literary analysis. - Structured Analysis:

Each body paragraph follows a clear structure, beginning with a claim, supported by evidence, followed by analysis, and ending with a connection to the thesis. The analysis focuses on explaining how the evidence strengthens the argument rather than simply summarizing the plot.

AP Literature analysis essay examples for students

Example # 3: Hamlet (Theme of Madness and Reality) Novel analysis

Level: Early College

Length: 520 words

The play's the thing": Metatheatricality in Hamlet

Hamlet is obsessed with acting, characters feign madness, perform grief, and stage plays. Central to this theatrical self-awareness is "The Mousetrap," the play within a play that Hamlet uses to "catch the conscience of the king" (Shakespeare 2.2.633). But Shakespeare's metatheatrical device does more than advance the plot. By staging a performance that mirrors the main action, Shakespeare questions whether authentic emotion and performed emotion can be distinguished, ultimately suggesting that in both theater and life, sincerity and performance are inseparable.

Hamlet's instructions to the players reveal his anxiety about authentic versus artificial expression. He warns them not to "o'erstep... the modesty of nature" and criticizes actors who "tear a passion to tatters" (3.2.19-20, 9). Hamlet wants naturalistic acting that appears unstudied, yet the very need for such instruction reveals a paradox: the most convincing performance is one that doesn't appear to be a performance. Hamlet himself performs madness throughout the play, carefully calibrating his behavior to seem spontaneous. When he tells Gertrude, "I essentially am not in madness, / But mad in craft" (3.4.187-188), he acknowledges that his "real" self is constructed through performance. If Hamlet can only be authentic by performing, then where is the authentic Hamlet?

"The Mousetrap" functions as a mirror that reflects and amplifies the play's action. The performed murder of Gonzago recreates Claudius's murder of Old Hamlet, but with crucial differences, Gonzago is poisoned in his ear in a garden, exactly as Claudius poisoned his brother, yet this is staged fiction rather than secret history. When Claudius reacts by abruptly ending the performance, his response becomes its own kind of performance watched by Hamlet and Horatio. The theatrical audience (us) watches a staged audience (Danish court) watching a staged play (The Mousetrap). This layering of performances makes it impossible to locate where "reality" exists, every level is constructed for observation.

Hamlet's frustration with performance extends beyond theater to mourning itself. In the play's opening, Hamlet distinguishes his "inky cloak" of mourning from the "actions that a man might play," insisting his grief is authentic: "I have that within which passeth show" (1.2.77, 84-85). Yet when confronted with the Player who weeps for Hecuba, a fictional character, Hamlet is disturbed that the actor can "force his soul" to produce real tears for "nothing" (2.2.580-582). The Player's grief is performed, yet it produces genuine emotion. Hamlet's grief is supposedly genuine, yet it requires outward "shows", clothing, tears, sighs, identical to performance. If performed grief can become real, and real grief requires performance, then the categories collapse.

Through metatheatricality, Shakespeare suggests that life and theater operate by the same rules: both require performing roles convincingly. Hamlet claims to have authentic interiority ("that within which passeth show"), yet he can only express it through theatrical means, soliloquies, staged madness, directing plays. The boundary between authentic feeling and performed feeling dissolves. "The Mousetrap" doesn't just catch Claudius; it catches all the characters in the revelation that identity itself is theatrical. In a play where everyone is acting, the question isn't who is authentic, it's whether authenticity exists as anything other than a convincing performance.

What Makes This Example Work

- Analyzes Dramatic Technique:

This essay doesn't just discuss what happens in Hamlet; it examines how Shakespeare uses metatheatricality as a dramatic device. - Engages with Complexity:

Instead of arguing a simple thesis ("The play-within-a-play reveals Claudius's guilt"), the essay explores a more nuanced idea about performance and authenticity. - Uses Literary Terminology:

Terms like "metatheatricality" show familiarity with drama analysis. Using precise terminology demonstrates expertise. - Multiple Textual References:

The essay draws evidence from throughout the play, not just one scene. This shows comprehensive engagement with the text.

Example # 4: Character Analysis Example: Elizabeth Bennet

Level: AP Literature / Early College

Length: 1,800 words

Elizabeth Bennet's (PEEL Structure)

Point: Elizabeth's initial prejudice against Darcy stems from wounded pride rather than an objective assessment of his character.

Evidence: When Darcy insults her at the Meryton ball, calling her "tolerable, but not handsome enough to tempt me," Elizabeth remains with no very cordial feelings toward him (Austen 13). Later, she readily believes Wickham's fabricated story about Darcy's supposed mistreatment, telling Jane that "Darcy's guilt... was beyond a doubt" despite having heard only Wickham's version (Austen 86).

Explanation: Elizabeth's quickness to judge Darcy reflects her wounded vanity. She is "tolerable" enough for others but not for the proud Mr. Darcy, and this rejection colors every subsequent interaction. Her intelligence, usually her greatest asset, becomes a liability because she uses it to construct a coherent narrative of Darcy's villainy rather than questioning her assumptions. The fact that she finds Wickham's accusations credible "beyond a doubt" based on one conversation reveals that she wants to believe ill of Darcy. This parallels the novel's broader critique of first impressions: both individual judgment and social reputation prove unreliable guides to character.

Link: Elizabeth's prejudice must be corrected through painful self examination, just as Darcy's pride must be humbled. The novel suggests that real understanding requires abandoning the comfort of hasty judgment.

What Makes This Work

- PEEL Structure:

A strong literary analysis paragraph begins with a clear point or claim, followed by textual evidence in the form of a quote. This is then explained through detailed analysis and finally linked back to the thesis or the broader meaning of the text. This structure is considered the gold standard for literary analysis paragraphs. - Character Focus:

The paragraph analyzes Elizabeth's internal psychology, not just her actions. It asks why she behaves as she does. - Connects to Theme:

The analysis links Elizabeth's individual prejudice to the novel's larger themes about judgment and social perception.

| For more infornation use our character analysis essay guide to learn how to analyze character traits, motivations, and development with textual evidence. |

Literary Analysis Essay Sample: College Level Examples

Example # 5: "The Yellow Wallpaper" Feminist Reading

Level: College

Length: 642 words

Unreliable Narration and Female Madness in "The Yellow Wallpaper"

Charlotte Perkins Gilman's "The Yellow Wallpaper" is narrated by a woman undergoing the "rest cure," a treatment for "nervous depression" that requires complete mental and physical inactivity (Gilman 1). As her condition deteriorates, her narration becomes increasingly fragmented, and she begins to see a woman trapped behind the room's yellow wallpaper. Most readings interpret this as a descent into madness caused by oppressive treatment. However, the story's power lies not in diagnosing the narrator's mental state but in how the first-person narration exposes the gendered medical authority that defines her as ill. By giving us only the narrator's perspective, one that male characters dismiss as unreliable, Gilman reveals how patriarchal medicine pathologizes women's legitimate experiences.

The narrator is positioned as unreliable from the story's opening. Her husband John, a physician, "laughs at me" when she suggests the house might be haunted, dismissing her feelings as "a slight hysterical tendency" (Gilman 1). The word "slight" is patronizing, John minimizes her concerns while simultaneously using them to justify medical control. The narrator herself internalizes this dismissal: "John is a physician, and perhaps... that is one reason I do not get well faster" (Gilman 1). The "perhaps" reveals her uncertainty about her own perceptions. She has been taught that her husband's medical authority supersedes her subjective experience. When she later says "personally, I disagree with their ideas" about the rest cure, the word "personally" is telling, her disagreement is framed as mere personal opinion, not valid knowledge (Gilman 1).

The wallpaper becomes a site where the narrator's perception diverges from accepted reality, and this divergence is what John labels madness. She describes it in increasingly intense detail: "It is dull enough to confuse the eye in following, pronounced enough to constantly irritate and provoke study" (Gilman 3). The wallpaper's pattern is genuinely chaotic; others notice its ugliness, yet the narrator's extended attention to it is treated as symptomatic. When she begins to see "a strange, provoking, formless sort of figure, that seems to skulk about behind that silly and conspicuous front design" (Gilman 5), the medical reading labels this a hallucination. But Gilman offers another possibility: the narrator sees a trapped woman in the wallpaper because she is a trapped woman. The figure behind bars isn't a delusion; it's a metaphor made literal through obsessive focus.

The story's climax forces readers to choose between the narrator's perspective and medical authority. When the narrator tears the wallpaper down and creeps around the room, John faints. She narrates: "Now why should that man have fainted? But he did, and right across my path by the wall, so that I had to creep over him every time!" (Gilman 15). From the medical perspective, the narrator has become completely mad. From her perspective, she has freed the trapped woman and achieved agency, even if that agency is only the ability to creep. John's fainting, his loss of consciousness and control, positions him as the one who cannot cope with reality. The narrator's repeated question, "why should that man have fainted?" invites readers to see his reaction as the unreasonable one.

Gilman's use of first-person narration is the story's most radical element. By never stepping outside the narrator's consciousness, Gilman denies readers access to objective medical authority. We cannot diagnose the narrator; we can only experience her progressive entrapment and her eventual psychological break that is simultaneously liberation. The ambiguity is the point. "The Yellow Wallpaper" reveals that women's "madness" is often the only available response to unbearable conditions. The rest cure didn't make the narrator well; it made her desperate enough to tear down walls. In a society that strips women of autonomy, the choice is between accepting captivity or being labeled insane. Gilman shows the narrator choosing the latter, and in doing so, questions whose definition of sanity we should accept.

What Makes This Example Work

- Historical Context:

The essay references the "rest cure" and 19th-century medical treatment. Placing the story in a historical context strengthens literary analysis. - Addresses Narrative Technique:

The essay doesn't just analyze what happens; it examines how Gilman's use of first person narration creates meaning. - Multiple Interpretations:

The essay acknowledges that readers could diagnose the narrator as mad, but offers an alternative feminist reading. Sophisticated analysis recognizes textual complexity. - Quotes Integrated Smoothly:

Notice how quotes are woven into sentences rather than dropped in as blocks. The analysis follows immediately after each quote.

NEED YOUR LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY WRITTEN?

Our professional writers craft essays that impress professors and earn top marks.

- Plagiarism-free guarantee on every paper

- 100% human-written by PhD literature specialists

- Deep textual interpretation with proper evidence integration

- Delivered on deadline with unlimited revisions

No AI shortcuts. Just expert-level quality.

Order NowPoetry analysis example

Example 6: "The Road Not Taken" Irony of Choice

Length: 850 words

Level: High School (Grade 10-11)

Title: The Irony of Inevitable Choice in Frost's "The Road Not Taken"

Most readers see Robert Frost's "The Road Not Taken" as an inspiring poem about individualism and choosing the unconventional path. But Frost's actual message is far more ironic: the poem satirizes how we retrospectively fabricate meaning from arbitrary choices. Through contradictory descriptions of the paths, conditional future tense, and the speaker's admitted uncertainty, Frost reveals that the human need to assign significance to decisions often exceeds the actual difference between our options.

The poem's central irony emerges in how the speaker describes the two paths. Initially, he claims one path is "less traveled by" (line 19), suggesting meaningful difference. Yet earlier, he contradicts this: "Though as for that the passing there / Had worn them really about the same" (lines 9-10). The paths are equally worn. Frost deliberately undermines the speaker's later claim of choosing the unconventional route. This contradiction exposes how we rewrite our personal histories, transforming random choices into purposeful decisions that define our identities.

Frost reinforces this irony through specific word choices that emphasize similarity rather than difference. The speaker notes the second path is "just as fair" (line 6) and "the passing there / Had worn them really about the same" (lines 9-10). The repetition of "same" and use of "equally" (line 11) stress equivalence, not distinction. When the speaker claims he "kept the first for another day" (line 13), he immediately admits "Yet knowing how way leads on to way, / I doubted if I should ever come back" (lines 14-15). This acknowledgment of life's irreversibility reveals the speaker's awareness that his choice is final and essentially arbitrary, both paths lead forward, neither offering clear superiority.

The poem's temporal structure reveals Frost's deeper critique of how we construct narratives about our lives. The entire poem exists in present tense as the speaker deliberates, except for the final stanza's dramatic shift: "I shall be telling this with a sigh / Somewhere ages and ages hence" (lines 16-17). This conditional future tense, "I shall be telling", imagines a future self who will assign the current moment retroactive significance. The "sigh" is ambiguous: satisfaction, regret, or mere dramatic effect? Frost leaves this intentionally unclear, suggesting the emotion is manufactured for the story, not inherent to the choice itself.

Most tellingly, Frost reveals the fabrication through the speaker's predicted claim: "I took the one less traveled by, / And that has made all the difference" (lines 19-20). The speaker hasn't taken this path yet; he's imagining what he'll say about it decades later. The future self will claim the path was "less traveled" despite the present self observing they were worn "really about the same." This gap between present reality (equivalent paths) and future narrative (unique choice) exposes how we retroactively impose meaning on moments that felt uncertain when we lived them.

Frost's structure reinforces this theme of false certainty. The poem's four five-line stanzas with an ABAAB rhyme scheme create a sense of orderly reflection, mirroring how we organize chaotic experiences into neat narratives. The regular meter (iambic tetrameter) provides rhythm suggesting reasoned contemplation. Yet this formal control contrasts with the speaker's actual uncertainty, "long I stood" (line 3), unable to decide. The tension between structured form and hesitant content reflects the gap between how we present our choices (confident, meaningful) and how we experience them (uncertain, arbitrary).

The poem's famous final lines gain power through irony rather than inspiration. "I took the one less traveled by, / And that has made all the difference" sounds triumphant when isolated. In context, it's an admission that we need our choices to matter, whether they do or not. Frost isn't celebrating individualism; he's gently mocking humanity's compulsion to see profound meaning in mundane decisions. The poem becomes a commentary on storytelling itself, how we craft our identities from choices that, in the moment, felt as random as picking between two identical forest paths.

Frost's genius lies in creating a poem that functions on two levels: surface inspiration for casual readers, deeper irony for careful analysis. The "road less traveled" has become a cultural cliché precisely because people miss Frost's point, we've turned his satire of false uniqueness into genuine inspiration. This misreading proves Frost right: we desperately want our choices to be meaningful, so much so that we'll ignore textual evidence to preserve that belief.

"The Road Not Taken" ultimately questions whether our choices define us or whether we define our choices. Frost suggests the latter: the roads are the same, but we need them to be different. Our identities emerge not from the objective importance of our decisions but from the stories we tell about them. The poem's enduring popularity, and persistent misreading demonstrate Frost's insight into human nature. We are all the speaker in the yellow wood, choosing arbitrarily between equivalent options, then spending the rest of our lives convincing ourselves and others that our choice "made all the difference."

What Makes This Poetry Analysis Work

1. Thesis Goes Beyond Surface Reading

- Argues the poem is ironic, not inspirational

- Makes a specific claim about technique (contradiction, temporal shift)

- Explains why it matters (how we construct personal narratives)

2. Close Reading of Specific Lines

- Quotes exact phrases with line numbers: "really about the same" (lines 9-10)

- Analyzes individual word choices: "same," "equally," "just as fair."

- Notices contradictions between stanzas

3. Poetic Technique Analysis

- Diction: Word choice showing similarity vs. difference

- Tone: Ironic vs. inspirational

- Structure: Temporal shift to conditional future

- Form: Regular rhyme/meter contrasting uncertain content

4. Pattern Tracking Throughout Poem

- Introduction: Paths described as similar

- Middle: Speaker admits uncertainty

- End: Future narrative contradicts present reality

- Shows deliberate authorial design, not random observation

5. Addresses Common Misreadings

- Acknowledges popular interpretation (inspiration)

- Explains why close reading reveals different meanings

- Uses textual evidence to support an alternative reading

6. Connects Form to Meaning

- Regular structure (ABAAB rhyme) = organized narrative we impose

- Hesitant content = actual uncertainty of choice

- Gap between form and content reinforces theme

| Need inspiration for your essay like the above example? Browse these literary analysis essay topics to guide your writing. |

Short Literary Analysis Example (High School Level)

Example # 7: Symbolism of the Conch in Lord of the Flies

Level: High School

Length: 500 words

When Ralph and Piggy discover the conch shell on the beach in Lord of the Flies, it becomes more than a tool for calling meetings. William Golding uses the conch to represent civilization, order, and democratic authority. As the boys' society breaks down, their treatment of the conch reflects their abandonment of civilized behavior. By tracing the conch from its discovery to its destruction, Golding shows how easily humans can lose the structures that separate them from savagery.

Initially, the conch establishes democratic order on the island. When Ralph blows it, boys emerge from the jungle, and they immediately agree to a rule: "We'll have to have 'Hands up' like at school... I'll give the conch to the next person to speak. He can hold it when he's speaking" (Golding 33). The conch becomes associated with the right to speak and be heard. This mirrors democratic societies where everyone has a voice. The fact that the boys institute this system themselves suggests humans have an innate understanding of fairness. The conch gives even Piggy, the most bullied boy, a chance to speak without interruption, something he never had before.

However, as Jack's hunters gain power, they begin to ignore the conch's authority. When Jack lets the signal fire go out, Ralph holds the conch and demands an explanation, but Jack refuses to acknowledge its power: "The conch doesn't count on top of the mountain" (Golding 43). By claiming the conch's authority applies only in some places, Jack begins to dismantle the democratic system. Later, when Piggy tries to speak at an assembly, Jack interrupts: "The conch doesn't count on this end of the island" (Golding 150). The conch's power depends on collective agreement to respect it. Once Jack and his hunters stop recognizing its authority, it becomes meaningless.

The conch's physical destruction coincides with the complete collapse of civilization on the island. When Piggy holds the conch and tries to appeal to reason, "Which is better, to have rules and agree, or to hunt and kill?", Roger pushes a boulder that kills Piggy and shatters the conch: "The rock struck Piggy... The conch exploded into a thousand white fragments" (Golding 180-181). The simultaneous destruction of Piggy and the conch is symbolic: both represent rationality, order, and democratic voice. Their elimination leaves only savage violence. After this moment, there are no more assemblies, no more debates, no more pretense of civilization.

Through the conch's arc, from powerful symbol of order to meaningless shell to shattered fragments, Golding illustrates how fragile civilization is. The boys didn't destroy the conch deliberately over time; they simply stopped respecting what it represented, and eventually eliminated it entirely. This suggests that maintaining civilization requires constant collective effort. The moment a society stops agreeing to respect shared rules and voices, those structures become as breakable as a seashell.

What Makes This Work

- Appropriate Complexity:

The thesis is clear and arguable without being overly sophisticated. It makes one main claim about symbolism. - Clear Structure:

Introduction with thesis leading to Body paragraphs tracking the symbol's development and a Conclusion connecting to broader meaning. - Sufficient Evidence:

Multiple quotes from different parts of the novel, properly cited. - Accessible Analysis:

The analysis explains how the evidence supports the claim without using overly complex literary terminology.

Comparative Literary Analysis Example (College Level)

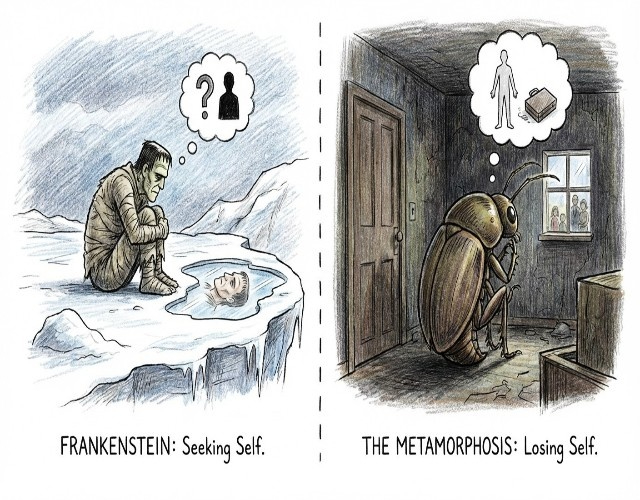

Example # 8: Isolation and Identity: Comparing Frankenstein and The Metamorphosis

Length: 300 words

Level: College level

Both Mary Shelley's Frankenstein and Franz Kafka's The Metamorphosis explore how physical transformation leads to social isolation, yet they reach opposite conclusions regarding the dependence of identity on social recognition. Frankenstein's creature begins with no identity and desperately seeks human connection to develop one, while Gregor Samsa begins with an established identity that gradually dissolves as his family withdraws recognition. Through these contrasting trajectories, Shelley suggests that identity requires social validation, while Kafka suggests that identity persists internally, even when society denies it.

Shelley's creature is born without language, culture, or relationships. He gains these by secretly observing the De Lacey family, learning that "I heard of the difference of sexes, and the birth and growth of children, how... each was useful to the other" (Shelley 115). The creature's education is entirely social; he becomes a person by learning how persons relate to each other. When Felix violently rejects him despite his eloquent speech, the creature loses faith in achieving human identity: "I am malicious because I am miserable... shall I respect man when he condemns me?" (Shelley 140). His turn to violence stems from being denied the social recognition necessary for identity. Without being seen as human, he cannot be human.

Kafka's Gregor, conversely, retains internal consciousness despite his insect body. Even as his family stops speaking to him and removes his furniture, Gregor thinks "as he was eager to find out what the others... would say at the sight of him" (Kafka 23). He maintains the desire for recognition that marks personhood. Yet his family's withdrawal of recognition, his sister declaring "we must try to get rid of it", gradually erodes his will to exist. Gregor's death suggests that while identity can persist internally without social validation, it cannot sustain itself indefinitely. Where Shelley's creature becomes violent when denied recognition, Kafka's Gregor simply fades away.

What Makes This Comparative Analysis Work

- Clear Comparative Thesis:

The thesis establishes both similarity (both texts explore isolation) and difference (they reach opposite conclusions about identity). - Parallel Structure:

Paragraph 1 addresses Shelley's creature seeking identity through recognition. Paragraph 2 addresses Kafka's Gregor losing recognition despite maintaining internal identity. This parallel makes the comparison clear. - Textual Evidence from Both:

The analysis quotes both texts, showing engagement with specific passages rather than general plot summary. - Synthesizes Rather Than Lists:

Instead of describing Shelley, then describing Kafka, the essay constantly moves between them to build a comparative argument.

Advanced Literary Analysis Example (College Level)

This excerpt shows the depth expected in college-level analysis.

Example # 9: Heart of Darkness "Colonial Power Through Unreliable Narration"

Level: College School

Length: 490 words

Narrative Unreliability and Colonial Power in Heart of Darkness

Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness has been alternately praised as a critique of imperialism and condemned as a racist text. This debate stems largely from the novel's narrative structure: Marlow, our narrator, describes African people in dehumanizing terms, yet the frame narrator presents Marlow's account without endorsement. Conrad's use of nested narration, a frame narrator reporting Marlow's story, creates interpretive instability. We cannot simply identify Conrad's views with Marlow's words, yet Marlow's perspective dominates the text. This narrative structure replicates the epistemological problem of colonialism itself: how can Europeans claim to understand Africa when their only access to it is mediated through colonizers' accounts? By making Marlow an unreliable narrator whose unreliability is difficult to measure, Conrad reveals that colonial knowledge is always already distorted, making any claim to understand the colonized subject impossible.

Marlow's descriptions of African people reveal his inability to see them as individuals. He repeatedly uses phrases like "a burst of yells," "a whirl of black limbs," and "black shapes" (Conrad 16-17). These mass nouns erase individuality, Africans appear as undifferentiated groups or body parts rather than persons. However, Conrad's text provides clues to Marlow's unreliability. When Marlow describes a dying African man "whose eyes looked at me with that wide, unfathomable look" (Conrad 18), the word "unfathomable" reveals Marlow's epistemological failure. He cannot read this man's interiority, so he projects inscrutability onto him. The frame narrator notes that Marlow's stories have "a quality of being... inconclusive" (Conrad 9), warning readers from the outset that Marlow is not a reliable guide. Yet readers are trapped in Marlow's perspective for the narrative, we have access to no other account of these events.

This interpretive trap mirrors the colonial situation Conrad critiques. European knowledge of Africa came exclusively through colonizers' accounts, explorers, missionaries, traders, none of whom were disinterested observers. Marlow acknowledges this when he says "the conquest of the earth... is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much. What redeems it is the idea only" (Conrad 10). The colonial "idea", bringing civilization, Christianity, commerce, functions as narrative justification for exploitation. Marlow recognizes this is a story colonizers tell themselves, yet he cannot step outside the epistemological framework colonialism creates. Even his critique of the Company's brutality reinscribes racial hierarchies; he objects to inefficient colonialism (the dying workers, the broken machinery) rather than the colonial project itself.

Conrad's formal choice to embed Marlow's narrative within another narrator's frame suggests that all knowledge of colonized peoples is mediated, filtered, and therefore unreliable. We never hear directly from African characters in the novel. They appear only as Marlow perceives them, and the frame narrator only reinforces Marlow's primacy by choosing to report his account. This silencing replicates colonial power structures where colonized subjects cannot speak for themselves within imperial discourse. Whether Conrad intended this as critique or unwittingly reproduced it is perhaps unanswerable, the text's formal structure makes the question undecidable.

What Makes This Work

- Theoretical Framework:

The essay engages with postcolonial theory and epistemology, using terms like "epistemological failure" and "colonial discourse." - Addresses Critical Debate:

The essay acknowledges scholarly controversy about whether Heart of Darkness is racist or anti-racist, then offers a nuanced reading. - Formal Analysis:

The essay examines narrative structure (frame narrative, unreliability) as central to meaning, not just content. - Textual Complexity:

The analysis recognizes that Conrad's text doesn't provide a single clear interpretation and explores this ambiguity as meaningful.

| If you want to write an essay as strong as the example above, the first step is to create a detailed outline. Refer to our literary analysis essay outline for guidance. |

Literary Analysis Introduction Example

Example # 10: Hook with a Question "The Catcher in the Rye" Authenticity vs. Phoniness

Text: The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger

Length: 96 words

Level: High School / AP Literature

The Introduction

Everyone Holden Caulfield meets is a "phony", except the people who never pretend to be anything they're not. In J.D. Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye (1951), sixteen-year-old Holden's cynical dismissal of the adult world masks a deeper fear: that growing up requires abandoning authenticity for social performance. Through Holden's fixation on childhood innocence, symbolized by his fantasy of catching children before they fall off a cliff into adulthood, Salinger reveals that adolescent rebellion often stems from terror of becoming the very phoniness one criticizes.

What Makes This Introduction Work

1. Strong Hook (First Sentence)

- Opens with the character's central obsession

- Uses specific language from the novel ("phony")

- Creates paradox (everyone is phony except those who aren't)

- Why it works: Immediately establishes the essay's analytical focus

2. Essential Context (Second Sentence)

- Author's full name: J.D. Salinger

- Complete title in italics: The Catcher in the Rye

- Publication date: (1951)

- Character detail: sixteen year old Holden

- Why it works: Provides necessary information efficiently

3. Analytical Thesis Statement (Final Sentence)

- What: Holden's fixation on childhood innocence (specific element)

- How: Through the "catcher" fantasy symbol (technique)

- Why it matters: Rebellion = fear of becoming what you hate (interpretive claim)

- Why it works: Makes an arguable interpretation beyond surface level reading

4. Evidence Preview

- Mentions key symbol: Catcher in the Rye

- References pattern: cynicism masking fear

- Why it works: Shows essay will analyze technique, not just describe plot.

Alternative Hook Options for This Same Essay

Hook Type 1: Provocative Question

| "Why does a teenage boy spend an entire novel calling everyone fake while wearing a ridiculous hunting hat?" |

Hook Type 2: Striking Observation

| "Holden Caulfield hates phonies more than anything, which makes him the biggest phony of all." |

Hook Type 3: Direct Address

| "If you've ever called someone 'fake,' you've channeled Holden Caulfield's favorite criticism." |

Example # 11: Hook with Surprising Claim "Frankenstein"

Text: Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

Length: 90 words

Level: High School / AP Literature

Everyone remembers the monster in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, but few remember that the monster is the novel's most sympathetic character. Victor Frankenstein abandons his creation immediately upon giving it life, repulsed by its appearance. The monster, by contrast, seeks connection and education, learning language and history by observing a family. He turns violent only after every human he encounters responds with horror. Through this reversal, making the "monster" more humane than his creator, Shelley challenges Romantic ideals about natural benevolence, suggesting that isolation and rejection, not inherent nature, create monstrosity.

What works:

- Opens with a counterintuitive claim that challenges common understanding.

- Provides context before stating the thesis.

- Thesis makes a clear argument about what Shelley suggests.

- Previews the evidence structure (Victor vs. Monster).

Example 12: Hook with Relevant Context "Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre"

Text: Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë's

Length: 90 words

Level: College

During the Victorian era, women who displayed ambition or sexual desire were often diagnosed with "hysteria" and institutionalized. Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre, published in 1847, features Bertha Mason, Rochester's first wife, locked in the attic and dismissed as mad. For most of the novel, Bertha is presented through Rochester's perspective as an inhuman creature. However, when Bertha finally appears directly, she burns down Thornfield Hall, an act that frees Jane from a marriage built on deception. Rather than simply depicting madness, Brontë uses Bertha to reveal how patriarchal marriage drove women to desperate acts, then labeled their resistance as insanity.

What works:

- Opens with a historical context that illuminates the text.

- Identifies how the novel is typically read.

- Thesis offers a more complex interpretation.

- Links character (Bertha) to broader themes (patriarchal marriage).

Key Patterns Across These Examples

1. Thesis Patterns: Strong theses make specific claims about authorial technique and meaning. These demonstrations show thesis construction in action, how to move from observation to an arguable interpretation.

2. Evidence Usage: Each demonstration integrates quotations with immediate analysis. Notice the pattern: provide context, include a quotation, explain its significance in three to four sentences, and connect it back to the thesis.

3. Organization Approaches: None follow chronological plot order. They jump between textual moments based on analytical points, showing how to organize by argument rather than page sequence.

4. Level Progression: High school demonstrates single-element analysis. AP connects the technique to meaning. College integrates research and theory. Match your writing to your assignment level.

Want analysis as strong as the above given examples for your assigned text? Our professional essay writing service expert analysts break down complex literary techniques, identify patterns you missed, and build evidence-backed arguments, custom analysis for any book, play, or poem.

Strategies for Applying These Examples to Your Own Writing

Don't copy these examples. Instead, use them as models for developing your own analysis skills.

| Step | Action | Tip |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Read example | Match your assignment type |

| 2 | Note structure | Thesis, topic sentences, transitions |

| 3 | Check annotations | Understand why techniques work |

| 4 | Count elements | Quotes, analysis sentences, paragraph length |

| 5 | Adapt | Use your own ideas, don’t copy |

Download Free Literary Analysis Examples (PDFs)

Better Essays. Better Grades. Less Stress.

Our professional writers have helped thousands of students succeed; you're next.

- 100% plagiarism-free, original work

- Expert writers across 50+ subjects

- Fast delivery, even last-minute orders

- Satisfaction guaranteed or money back

Trusted. Confidential. 100% human written.

Order NowFrom Examples to Your Own Excellence

These six annotated literary analysis demonstrations show effective thesis development, strategic evidence integration, and analytical depth across high school, AP, and college levels. Study the margin notes explaining why specific strategies work, then apply those techniques to your own analysis.

Your genuine curiosity about literary patterns produces stronger analysis than manufactured interest. Choose texts and angles where you've noticed something interesting worth exploring.

Ready to start your own literary analysis essay? Begin with our literary analysis essay guide for in-depth support with thesis development, evidence selection, and revision strategies.

-19577.jpg)