Example 1: Social Media Users (Beginner Level - 1,200 words)

Topic: Classification by engagement level

Categories: 3 (Lurkers, Casual Sharers, Content Creators)

Level: Foundational, clear structure, straightforward examples

Best for: First classification essay, 750-1,200 word assignments

[KEY SECTIONS WITH ANNOTATIONS]

[INTRODUCTION - 150 words] Scroll through any social media platform and you'll notice distinct behavioral patterns: some accounts never post, others share occasionally, while some generate constant original content. With over 4.5 billion social media users worldwide, understanding these engagement differences reveals how platforms have created distinct participation pathways that shape modern digital communication.

Social media users can be classified by engagement level into three distinct types: lurkers who observe passively, casual sharers who participate occasionally, and content creators who produce original material regularly. This classification matters because each group serves essential functions in maintaining platform ecosystems content creators produce material that casual sharers amplify and lurkers consume, creating the engagement cycle platforms depend on. Understanding these patterns helps users navigate digital spaces intentionally rather than unconsciously adopting behaviors that don't serve their goals.

Annotation:

|

[CATEGORY 1: LURKERS - 300 words]

Lurkers represent the majority of social media users those who consume content without actively participating through posts, comments, or reactions. This group follows 100+ accounts but posts 0-2 times yearly, spending 30-60 minutes daily scrolling feeds while maintaining private or empty profiles.

Sarah exemplifies this behavior: she has maintained her Instagram account for five years, follows 247 accounts including friends, fashion brands, and travel influencers, and scrolls through her feed during her morning commute and lunch breaks. However, her profile shows only three posts, all from 2020, during a vacation, and she has never commented on anyone's content or responded to stories. She knows intimate details about acquaintances' lives from their posts but remains invisible herself.

Similarly, Tom uses Twitter to follow tech news and industry leaders, checking his feed 4-5 times daily to stay current on developments in artificial intelligence and software engineering. His account has zero tweets, zero followers, and a default profile picture. He absorbs information from hundreds of accounts without ever contributing his own perspective or engaging with other users' content.

This pattern demonstrates lurkers' preference for information access without the obligation to perform publicly or maintain a visible persona. Research suggests lurkers represent 80-90% of most platforms' user bases despite their invisibility to other users. They value social media as a window into others' lives and a source of information, news, and entertainment, but reject the pressure to curate their own public image or engage in performative sharing.

Annotation:

|

Need Real Examples? Get a Custom Classification Essay with Authentic Samples!

Tired of Generic Guides? We Create Essays Packed with Concrete, Relevant Examples

- Custom-researched examples tailored to your topic

- Real-world illustrations that bring your categories to life

- Seamless integration of evidence to support your argument

- Citations from credible, up-to-date sources

Go beyond theory. Get an essay that shows and tells.

Order Now[CATEGORY 2: CASUAL SHARERS - 350 words]

While lurkers remain invisible, casual sharers take a more visible but still limited approach to social media engagement. This group posts 1-3 times monthly, engages with others' content through likes and occasional comments, and maintains somewhat active profiles without feeling compelled to share constantly.

Jessica represents typical casual sharer behavior: she posts on Instagram 8-12 times annually, usually when traveling, attending special events, or celebrating milestones. Her last six posts include her sister's wedding (two photos), a hiking trip to Yosemite (one landscape), her new apartment (three photos), and her birthday dinner (one group photo). Between posts, she likes 20-30 friends' posts weekly and comments "Congrats!" or "Love this!" every few days. Her engagement is genuine but sporadic; she participates when motivated by specific occasions rather than maintaining a consistent presence.

Marcus shows similar patterns on Facebook: he shares articles about politics and local news 2-3 times monthly, posts family photos during holidays, and comments on close friends' major life updates. He checks Facebook daily but contributes content only when something feels worth sharing to his 300 connections. Unlike content creators who post multiple times daily, Marcus views social media as a tool for occasional connection rather than constant self expression. His posts generate 15-40 likes and 3-8 comments from his established network, satisfying his desire for low key social connection without demanding continuous content creation.

This middle ground approach reflects casual sharers' balanced relationship with social media. They recognize platforms' value for maintaining relationships and sharing significant moments, but reject the time investment and self promotion content creation requires. They post when they have something worth sharing rather than feeling pressure to maintain algorithmic favor through frequent updates. This group often expresses frustration with both extremes, they find lurkers too disconnected and content creators too performative, preferring their selective engagement style.

Annotation:

|

[CATEGORY 3: CONTENT CREATORS - 350 words]

Content creators represent the most visible minority of social media users, those who produce original material regularly, invest significant time in content development, and build followings through consistent posting. This group posts daily or multiple times daily, carefully curates aesthetic or brand identity, and often views social media as a platform for influence, income, or professional development.

Amanda exemplifies dedicated content creation: she manages her Instagram account like a part time job, photographing 20-30 outfit combinations weekly, spending 2-3 hours daily editing images in Lightroom and writing captions, and maintaining a consistent 6 AM posting schedule across Instagram, TikTok, and Pinterest. Her 50,000+ followers expect daily fashion inspiration, and she delivers through stories, reels, carousel posts, and interactive polls. She tracks engagement metrics obsessively, adjusts content strategy based on performance data, and collaborates with brands for sponsored content. Social media isn't just a hobby, it's her primary income source and professional identity.

Similarly, David has built a YouTube channel and Twitter presence around tech reviews, posting 3-4 videos weekly and tweeting 10-15 times daily about technology news, product launches, and industry trends. He spends 30+ hours weekly scripting videos, filming, editing, and engaging with his 200,000 subscribers through comments. His content calendar is planned weeks in advance, and he treats his channels as a full time career requiring constant attention and strategic planning.

Content creators drive platform evolution and set trends that casual sharers amplify and lurkers consume. They're motivated by various factors: income potential, creative expression, community building, professional branding, or influence. Despite representing only 1-9% of platform users, they generate the majority of original content and shape platform culture through their consistent presence and audience relationships. Their significant time investment, often 15-40 hours weekly, distinguishes them clearly from both casual sharers and lurkers.

Annotation:

|

[CONCLUSION - 150 words]

Understanding social media users through engagement levels, lurkers, casual sharers, and content creators reveals the distinct participation pathways that shape online communities. These three categories exist in a symbiotic relationship: content creators produce the material that casual sharers amplify through likes and shares, which lurkers then consume, creating the engagement ecosystem platforms depend on. Each group serves essential functions rather than representing "better" or "worse" usage.

As social media continues evolving, recognising these patterns helps users engage intentionally rather than unconsciously adopting behaviours driven by platform algorithms or social pressure. Whether someone chooses to lurk, share casually, or create content depends on personal goals, available time, and desired relationship with digital spaces. The key is conscious choice about engagement level rather than passive participation shaped by external expectations.

Annotation:

|

What Makes This Example Effective

- Single consistent organizing principle: Engagement level applied uniformly to all three categories

- Mutually exclusive categories: Clear boundaries users fit obviously into one category without overlap

- Balanced development: Each category paragraph 300-350 words with 2 detailed examples

- Specific concrete examples: Names (Sarah, Tom, Jessica), numbers (247 accounts, 4-5 times daily), observable behaviors

- Parallel structure: Each category follows same pattern (definition; example 1; example 2; and analysis)

- Smooth transitions: Connections between categories ("While lurkers remain invisible, casual sharers...")

- Strong thesis: Names topic, organizing principle, and all three categories clearly

- Synthesizing conclusion: Shows relationships between categories, offers broader significance

Visit our Classification Essay Outline and download templates matching these example structures

Example 2: College Student Study Habits (Intermediate - 1,500 words)

Topic: Classification by deadline management approach

Categories: 3 (Procrastinators, Steady Workers, Overachievers)

Level: Intermediate, deeper analysis, research integration

Best for: 1,200-1,500 word assignments, some research required

[KEY SECTIONS WITH ANNOTATIONS]

INTRODUCTION (180 words): At 11:58 p.m., laptops glow across dorm rooms, coffee cups stack beside keyboards, and assignment portals refresh anxiously as deadlines creep closer. For college students, time pressure is not an occasional inconvenience but a defining feature of academic life. Despite access to planners, productivity apps, and syllabi issued weeks in advance, procrastination remains widespread. Studies indicate that nearly 65% of college students report delaying academic tasks, often despite knowing the consequences. Yet procrastination is only one way students respond to deadlines. Walk through any campus library and you will see sharply different rhythms of work: some students racing the clock, others moving steadily through the semester, and a few finishing long before the pressure arrives. These patterns are not random habits but recognizable approaches to deadline management. College students can be classified by their approach into three distinct types: procrastinators who rely on pressure to perform, steady workers who maintain consistent schedules, and overachievers who complete assignments well before deadlines. Each group navigates time, stress, and motivation differently, revealing that deadline management is less about discipline alone and more about personal strategy.

Annotation:

|

CATEGORY 1 - PROCRASTINATORS (400 words):

At 11:00 p.m., Mike finally opens the document titled “Final Research Paper.” The deadline is 8:00 a.m. His roommate is asleep, the campus is quiet, and the panic has arrived right on schedule. Mike cracks open his first energy drink and starts typing. Words spill faster than expected eight hundred, then a thousand an hour. By sunrise, three empty cans line his desk. He submits the paper at 7:47 a.m., heart racing but oddly satisfied. For Mike, urgency is not a barrier to productivity; it is the trigger.

Procrastinators like Mike delay tasks until deadlines loom, believing pressure sharpens their focus. Elena, another student in this category, begins studying just eighteen hours before her final exam. While her classmates spread revision over weeks, Elena insists that early studying feels pointless. Only when time feels scarce does she enter what she calls her “mental tunnel,” blocking distractions and absorbing material at high speed. For these students, deadlines act as alarms rather than guides.

Research supports the prevalence of this behavior. Approximately 20–30% of college students identify as chronic procrastinators, regularly postponing tasks regardless of difficulty or importance. Contrary to popular belief, many are not lazy or disengaged. Instead, they associate last minute work with adrenaline, clarity, and momentum. However, this approach carries risks. Technical issues, unexpected interruptions, or underestimated workloads can quickly turn manageable stress into academic disaster.

Despite the drawbacks, procrastinators often point to successful outcomes as proof of effectiveness. They remember the papers submitted just in time and the exams passed against the odds, reinforcing the habit. What remains unseen is the cumulative toll: disrupted sleep, heightened anxiety, and inconsistent performance. Procrastinators survive on bursts of intensity, but their success depends heavily on circumstances aligning perfectly. When they do not, the cost can be severe.

Annotation:

|

CATEGORY 2 - STEADY WORKERS (400 words):

While some students sprint toward deadlines, steady workers move at a controlled, predictable pace. Sara opens her planner every Sunday night, blocking out study hours between classes, club meetings, and part time work. When assigned a research paper, she begins within days not with frantic writing, but with quiet preparation. One day is for reading sources, another for outlining, another for drafting. The deadline is not ignored, but it never feels threatening.

Steady workers rely on consistency rather than urgency. Daniel, for example, studies two hours each weekday evening, regardless of whether an exam is scheduled. His routine rarely changes, and neither does his stress level. Assignments are completed incrementally, often days before they are due, but without the intensity seen in overachievers. For steady workers, productivity is not dramatic; it is habitual.

This group often benefits from balanced time management. By spreading tasks evenly across the semester, steady workers reduce cognitive overload and avoid burnout. They are less likely to pull all nighters or rely on caffeine fueled marathons. Instead, their academic life blends smoothly with personal commitments. When unexpected challenges arise, they have flexibility because their schedule is not already stretched to the limit.

However, steady workers are not immune to challenges. Their approach requires discipline and self awareness. Falling behind even slightly can disrupt the system, and without the motivating force of panic, some struggle when interest fades. Still, this group represents a practical middle ground between extremes.

Steady workers demonstrate that success does not require perfection or pressure. Their strength lies in predictability and moderation. While they may not experience the adrenaline rush of procrastinators or the polish of overachievers, they often achieve reliable outcomes with manageable stress an advantage that becomes increasingly valuable as academic demands grow.

Annotation:

|

CATEGORY 3 - OVERACHIEVERS (400 words): Rachel completes assignments 1-2 weeks early, revises multiple drafts, seeks professor feedback proactively. James studies 4-5 hours daily even when no tests scheduled. Represents 15-20% of students but creates stress through perfectionism.

Annotation:

|

CONCLUSION (180 words): Synthesizes all three approaches. Notes no "best" approach depends on personality, course load, life circumstances. Encourages conscious strategy selection based on self awareness.

Annotation:

|

What Makes Example 2 More Advanced

- Research integration: Includes 5-6 statistics and research findings naturally

- Nuanced analysis: Discusses both benefits and drawbacks of each approach

- Deeper examples: More specific details (hours studied, word counts, timing)

- Psychological insight: Explores motivations and consequences beyond surface behavior

- Longer paragraphs: 400 words per category vs. 300 allows deeper exploration

- Complex conclusion: Acknowledges gray areas and individual variation

See our diverse Classification Essay Topics and browse 240+ topics to find inspiration.

Example 3: Leadership Styles (Advanced - 1,800 words)

Topic: Classification by decision making authority

Categories: 4 (Autocratic, Democratic, Laissez Faire, Transformational)

Level: Advanced research, organizational theory, complex analysis

Best for: 1,800-2,500 word research papers, upper level coursework

[KEY SECTIONS WITH ANNOTATIONS]

INTRODUCTION (220 words): Opens with leadership crisis example. Establishes organizational psychology framework. Thesis integrates four categories with theoretical foundations (Blake Mouton Managerial Grid, Lewin's leadership styles).

Annotation:

|

CATEGORIES (4 × 400 words each = 1,600 words total):

Each category includes:

- Theoretical definition from leadership literature

- 2-3 real world examples (mix of historical leaders and contemporary cases)

- Research on effectiveness (quantitative data)

- Situational analysis (when approach works vs. fails)

- Comparison to other categories

Example - Autocratic Leaders: Steve Jobs example with specific product decisions (iPhone development secrecy). Research showing 23% higher short term productivity but 34% higher turnover. Analysis of when autocratic approach succeeds (crisis situations, time sensitive decisions) vs. when it fails (creative industries, knowledge work).

Annotation:

|

CONCLUSION (180 words): Meta analysis of all four approaches. Discusses hybrid leadership (combining styles situationally). References current trends (adaptive leadership, emotional intelligence). Ends with implications for leadership development.

Annotation:

|

What Makes Example 3 Advanced

- Theoretical framework: Grounds classification in academic literature (Blake Mouton, Lewin)

- Research heavy: 10+ citations integrated naturally throughout

- Four categories: More complex than typical 3 category structure

- Situational analysis: Discusses context dependent effectiveness for each style

- Real world examples: Mix of historical figures and contemporary cases with verifiable details

- Quantitative data: Specific percentages on effectiveness metrics

- Academic tone: Formal but accessible, uses discipline specific terminology correctly

- Meta analysis: Conclusion goes beyond categories to discuss classification system itself

Graduate Student? Get a Master's or PhD-Level Classification Essay!

Your classification essay deserves graduate-level expertise, and we deliver!

- Writers with advanced degrees in your specific field

- Sophisticated category systems and theoretical frameworks

- Research integration and proper academic citations

- Publication-quality writing and analysis

Elevate your academic work with our graduate writing specialists!

Order TodayClassification Essay Examples By Expertise Level

Example 4: The Types of Sustainable Consumers (Beginner/Intermediate)

Introduction

In today's marketplace, "going green" is a popular mantra, but not all environmentally conscious shoppers follow the same path. Their purchasing decisions reveal distinct philosophies and levels of commitment to sustainability. By examining their primary motivations and consistent behaviors, we can classify sustainable consumers into three clear categories: the Budget Conscious Eco-Shopper, the Ethical Purist, and the Trend Driven Green Adopter.

Body Paragraph 1: The Budget Conscious Eco-Shopper

This consumer's primary motivation is long term savings, with environmental benefit as a welcome bonus. They are driven by efficiency and waste reduction because it saves money. Their most common sustainable practice is reducing energy consumption switching to LED bulbs, improving home insulation, and unplugging devices to lower utility bills. They are also drawn to durable, high quality goods that won't need frequent replacement and are masters of reuse, such as repurposing glass jars for storage. Their philosophy is practical: the most sustainable choice is often the one that is most economical over time.

Body Paragraph 2: The Ethical Purist

For the Ethical Purist, sustainability is a non negotiable value system rooted in environmental and social ethics. Their purchasing decisions are research intensive, focusing on a product's entire lifecycle. They prioritize certifications like Fair Trade, organic, and B-Corp, and they actively avoid companies with poor environmental records. This consumer will buy a locally made, plastic free product from a small brand over a cheaper, "greenwashed" alternative from a major corporation. Their activism extends beyond shopping to include advocacy, community gardening, and repairing items to extend their life, seeing consumption as a direct vote for the world they want.

Body Paragraph 3: The Trend Driven Green Adopter

This consumer engages with sustainability as a lifestyle trend, influenced heavily by social media and mainstream marketing. They are attracted to innovative, branded "eco-friendly" products that are visible and stylish, such as reusable coffee cups from popular brands, chic recycled plastic sneakers, or subscription boxes for zero waste kits. Their adoption is often selective, focusing on convenient or high visibility items without a deep integration of sustainable principles into other life areas. While their choices increase the demand for green products, their commitment may fluctuate as trends change.

Conclusion

Classifying sustainable consumers into these three types driven by budget, ethics, or trends reveals that the movement is not monolithic. Each group contributes to environmental impact reduction, but their pathways and motivations differ significantly. Understanding this spectrum is crucial for businesses aiming to communicate effectively and for individuals reflecting on their own consumption patterns. True progress may rely on appealing to the pragmatism of the Budget Conscious, the values of the Purist, and the social appeal for the Trend Driven Adopter simultaneously.

Annotations for "The Types of Sustainable Consumers":

|

Example 5: Musical Listeners: Why We Press Play (Intermediate)

Introduction

Music is a universal human experience, but our reasons for seeking it out are deeply personal. Beyond genre preferences, we can classify listeners based on the fundamental psychological or emotional need that music fulfills for them. These purposes create three distinct listener identities: the Emotional Regulator, who uses music to manage feelings; the Cognitive Focuser, who uses it as a tool for concentration; and the Social Connector, for whom music is a bridge to others.

Body Paragraph 1: The Emotional Regulator

For this listener, music is a form of self therapy or an emotional amplifier. They consciously create playlists to match or alter their mood. A person feeling nostalgic might listen to songs from their high school years, while someone needing energy before a big event queues up an empowering, high tempo anthem. The Emotional Regulator also uses music to process complex feelings like sadness or anger, finding catharsis in lyrics that articulate their inner state. Their music library is organized by feeling ("Chill," "Pump Up," "Heartbreak") rather than just artist or genre, demonstrating its functional role in emotional management.

Body Paragraph 2: The Cognitive Focuser

The Cognitive Focuser employs music primarily as an auditory tool to enhance productivity or mental performance. They are less concerned with lyrical content and more with sonic qualities like tempo, rhythm, and the absence of distracting vocals. This listener might use repetitive ambient music, film scores, or lo-fi beats to create a "sound bubble" that masks environmental noise and helps sustain concentration during work, study, or reading. For them, the ideal music is immersive yet ignorable it structures mental space without demanding active listening, turning background sound into a performance enhancing foreground tool.

Body Paragraph 3: The Social Connector

For the Social Connector, music's primary value is its power to forge, strengthen, or express social bonds. Their listening is deeply communal. This includes sharing headphones with a friend, creating collaborative playlists for a road trip, or the collective experience of a live concert. Music serves as a key part of their identity and a way to signal belonging to a group, whether it's a generation, subculture, or circle of friends. They discover new music through social recommendations and often associate specific songs with specific people or shared memories, making their musical experience inherently relational.

Conclusion

Classifying listeners by purpose such as emotional, cognitive, or social reveals that music's function is as varied as its forms. One person's focus aid is another's emotional catharsis and another's social glue. This framework explains why debates over "the right way" to listen are futile; the experience is defined by the listener's intent. Recognizing our own primary mode can help us curate more fulfilling musical experiences and appreciate the different roles music plays in the lives of others.

Annotations for "Musical Listeners":

|

Example 6: Digital Citizenship in the Age of Misinformation (Advanced)

Introduction

Navigating the digital information ecosystem requires more than just literacy; it requires a specific set of ethical and critical engagement practices as a form of digital citizenship. In an era of rampant misinformation, users can be classified by their level of defensive awareness and proactive integrity. This taxonomy identifies three distinct types: the Vulnerable Consumer, prone to passive acceptance; the Skeptical Verifier, who practices active defense; and the Ethical Amplifier, who champions positive discourse.

Body Paragraph 1: The Vulnerable Consumer

The Vulnerable Consumer engages with online information passively and often uncritically. They are characterized by high exposure but low scrutiny, making them susceptible to misinformation and emotional manipulation. Typical behaviors include scrolling news feeds rapidly, sharing headlines without reading articles, and prioritizing content that aligns with their existing beliefs (confirmation bias). Their engagement is often driven by emotion, leading them to amplify sensationalist or polarizing content without checking sources. This group forms the ideal target for malicious actors and algorithmically generated "rage bait," as their sharing patterns inadvertently increase the reach of low credibility information.

Body Paragraph 2: The Skeptical Verifier

Operating from a stance of defensive skepticism, this citizen employs critical thinking as a shield. Their core practice is lateral reading leaving the original source to check credibility through other established sites. They look for primary sources, check dates, examine author credentials, and use fact checking organizations. The Skeptical Verifier is adept at recognizing emotional language, dubious domain names, and the hallmarks of manipulated media. While they protect themselves and their immediate network from falsehoods, their engagement is often defined by negation (calling out falsehoods) rather than the proactive creation or promotion of quality information.

Body Paragraph 3: The Ethical Amplifier

The Ethical Amplifier adopts a proactive, constructive approach to digital citizenship. Their goal is to improve the information ecosystem itself. They consciously share content from vetted, authoritative sources, provide helpful context when posting, and respectfully correct misinformation within their communities by citing reliable evidence. This group understands platform algorithms and seeks to "feed the beast" with integrity, boosting signal over noise. They often support quality journalism and may create original content that synthesizes complex issues accurately. Their mindset is custodial, viewing their online activity as a contribution to a shared public square.

Conclusion

This classification reveals that digital citizenship is a spectrum of responsibility, from passive vulnerability to active stewardship. While the Skeptical Verifier is essential for defense, a healthy democracy requires citizens to graduate to the role of Ethical Amplifier. The fight against misinformation is not won by skeptics alone but by a critical mass of users who intentionally and ethically amplify truth. Thus, this model serves as both a diagnostic tool for one's own habits and an aspirational roadmap for strengthening our collective digital discourse.

Annotations for "Digital Citizenship":

|

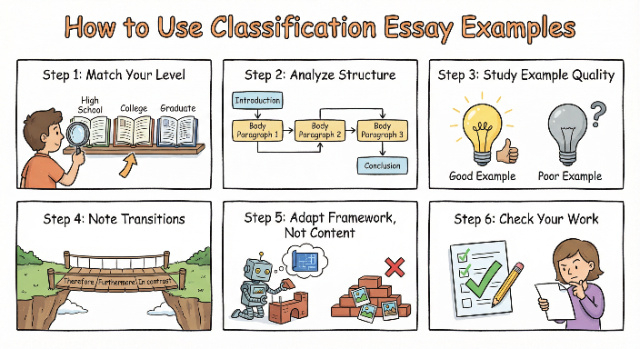

How to Use These Classification Essay Examples Effectively

Step 1: Match Your Level

- First classification essay? Study Example 1 (beginner)

- Have essay experience? Study Example 2 (intermediate)

- Upper level course? Study Example 3 (advanced)

Step 2: Analyze Structure

- Notice introduction flow:

- hook

- context

- thesis

- See category paragraph pattern:

- definition

- examples

- analysis

- transition

- Study conclusion approach: synthesis not summary

Step 3: Study Example Quality

Replace generic descriptions with concrete details:

- Weak: "Content creators work hard"

- Strong: "Amanda spends 2-3 hours daily editing 20-30 photos"

Step 4: Note Transitions

- "While lurkers remain invisible, casual sharers..."

- "Unlike procrastinators who wait, steady workers..."

- These connections guide readers through your classification

Step 5: Adapt Framework, Not Content

- Copy the organizational structure (intro format, category development pattern, conclusion approach).

- Create your own unique content for your topic.

- Think recipe structure with different ingredients.

Step 6: Check Your Work

- Single organizing principle used consistently?

- Mutually exclusive categories?

- Balanced paragraph lengths (within ±50 words)?

- 2-3 specific examples per category?

- Smooth transitions between categories?

See our classification thesis guide and master thesis formulas seen in these examples.

Classification Essay Examples: Key Takeaways and Success Patterns

Common Success Elements in Classification Essay Examples

1. Strong Organizing Principles

- Example 1: Engagement level

- Example 2: Deadline management approach

- Example 3: Decision making authority

All three principles create mutually exclusive categories applied consistently throughout.

2. Specific Examples Over Generic

Generic (weak): "Some students procrastinate and wait until the last minute."

Specific (strong): "Mike starts his 10 page research paper at 11 PM the night before the 8 AM deadline, types 800-1,000 words per hour fueled by three energy drinks, and submits at 7:47 AM."

3. Parallel Structure

All examples use consistent paragraph structure across categories:

- Topic sentence defining category

- Characteristics explanation

- Example 1 (detailed)

- Example 2 (varied but same pattern)

- Analysis explaining significance

- Transition (except last category)

4. Balanced Development

Word counts per category within ±50 words shows equal treatment:

- Example 1: 300-350 words per category

- Example 2: 400 words per category

- Example 3: 400 words per category

5. Synthesizing Conclusions

All three avoid simple summary. Instead they:

- Show relationships between categories

- Discuss broader implications

- Offer practical applications

- Leave readers with new insight

Need yours written professionally? Our professional essay writing service delivers human-written classification analysis with clear categories and concrete evidence.

Downloadable Resource

Download our complete classification essay examples resource for students and educators, ten full length, annotated models covering diverse topics from coffee drinkers to pet owners, each demonstrating clear category development, specific examples, and effective analytical structure.

Want the Best Grade Possible? Let Top Writers Handle Your Classification Essay!

Why settle for average when you can have our premium writing service?

- Top 5% of our writers selected for your essay

- Guaranteed quality with premium editing included

- Advanced category development and analysis

- Priority support and fastest turnaround times

Invest in your academic success with our best professionals!

Get Started NowClassification Essay Examples: Final Tips

Study these three examples, matching your skill level: beginner for straightforward structure and clear categories, intermediate for research integration and deeper analysis, and advanced for theoretical frameworks and complex synthesis. Visit our comprehensive classification essay guide and learn complete writing process from topic selection through revision

Notice the consistent elements across all levels: single organizing principle applied uniformly, specific examples with names and numbers replacing generic descriptions, parallel category structure, balanced development within 50 words per section, and synthesizing conclusions showing relationships beyond simple summary.

-19438.jpg)