What is a Cause and Effect Essay?

A cause and effect essay analyzes the relationship between events, specifically, it explains why something happened (the cause) and what resulted from it (the effect). Unlike argumentative essays that persuade or narrative essays that tell stories, this type focuses on explaining connections between events, actions, or phenomena.

Think of it like tracing dominoes. When one falls, it triggers the next. Cause & effect essays map these chain reactions with evidence and logic.

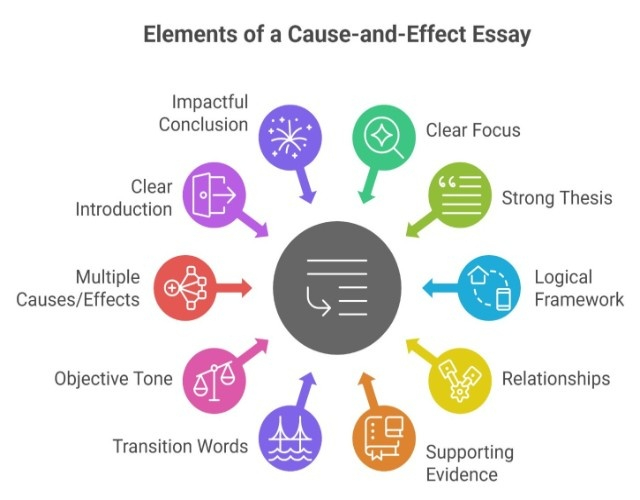

key elements/characteristics

A cause and effect essay explains why something happens and what happens as a result. Below are the essential elements that make a strong cause and effect essay.

1. Clear Cause-and-Effect Focus

A well-written cause and effect essay clearly identifies the causes, the effects, or both, keeping the discussion focused and relevant.

2. Strong Thesis Statement

The thesis clearly states the main cause-and-effect relationship that the essay will analyze.

3. Logical Essay Structure

Effective cause and effect essays follow a logical structure, such as:

Block structure (causes first, effects second)

Chain structure (one cause leading to multiple effects)

4. Clear Cause-and-Effect Relationships

Each cause is directly linked to its effect, avoiding weak or unsupported connections.

5. Supporting Evidence and Examples

Facts, examples, and explanations are used to support each cause & effect, strengthening the analysis.

6. Cause-and-Effect Transition Words

Common transition words like because, due to, leads to, as a result, and consequently help show relationships clearly.

7. Analytical and Objective Tone

The essay maintains an informative and analytical tone rather than relying on personal opinion.

8. Multiple Causes or Effects

Strong essays often discuss several causes or effects to provide depth and clarity.

9. Clear Introduction and Conclusion

The introduction presents the topic and thesis, while the conclusion summarizes the cause-and-effect relationships and their significance.

10. Logical and Impactful Conclusion

The conclusion reinforces the main ideas and explains why the cause-and-effect relationship matters.

Deadlines Don't Wait. Neither Should You.

Get a professionally written essay delivered to your inbox fast

- As fast as 3-hour turnaround

- Original content, zero plagiarism

- Subject-matter experts on every order

- Full privacy and confidentiality

100% human-written. Guaranteed.

Get Expert Help NowCause and Effect Essay Types

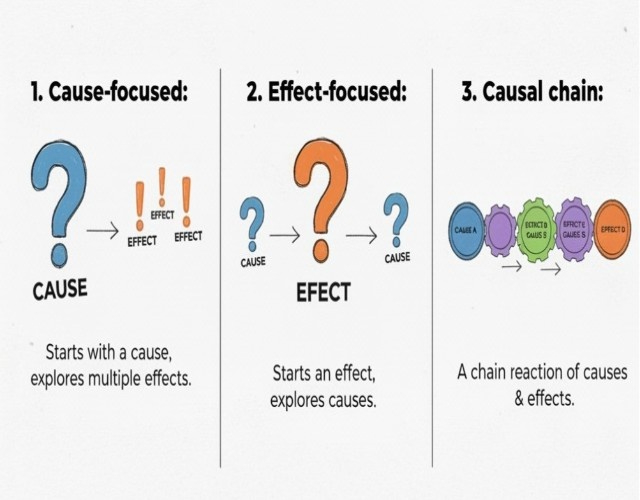

Cause and effect essays come in several forms. Here's where to learn about each:

1. Cause-focused: Examines multiple reasons behind one result.

2. Effect-focused: Explores multiple outcomes from one cause.

3. Causal chain: Shows how causes and effects link sequentially.

Choose the structure that matches your assignment question. For examples of each type, explore our cause and effect essay examples.

Understanding Cause and Effect Relationships

Before you write about causes and effects, you need to understand how they actually work. Not everything that happens together has a causal relationship.

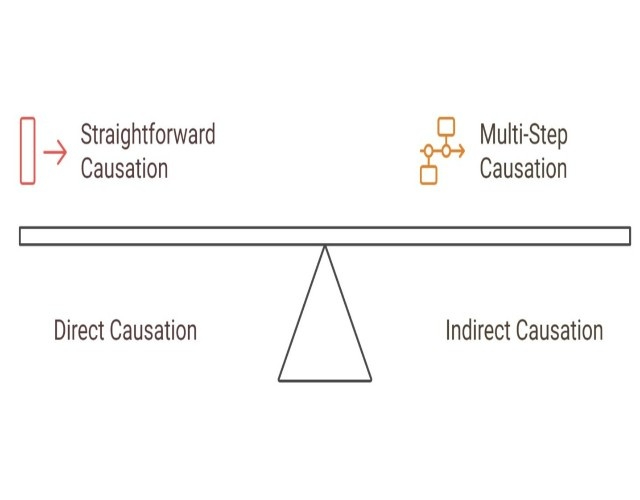

Direct vs. Indirect Causation

Direct causation is straightforward:

Direct causation is straightforward:

- Event A directly produces Event B with no intermediary steps.

- Turning a light switch causes the bulb to illuminate.

- Not studying directly causes poor test performance.

- Drunk driving directly causes accidents.

Indirect causation requires multiple steps in the chain:

- Economic recession doesn't directly cause divorce, but it creates job loss, leading to financial stress, causing relationship tension and divorce.

- Social media doesn't directly cause depression, but it creates comparison behavior leading to inadequacy feelings causing reduced self-esteem and depression symptoms.

Understanding this distinction helps you avoid oversimplifying complex issues.

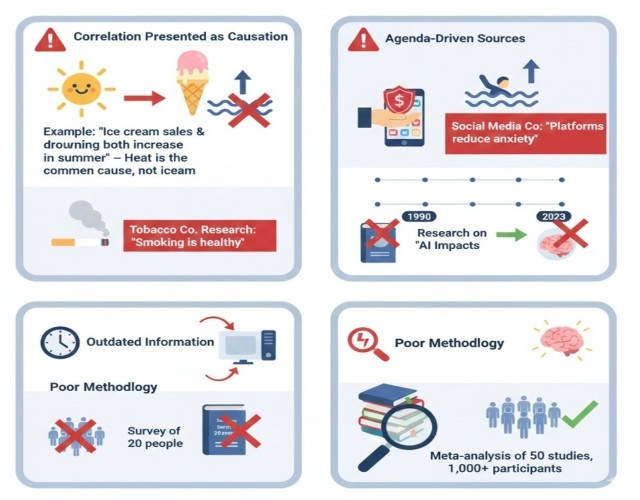

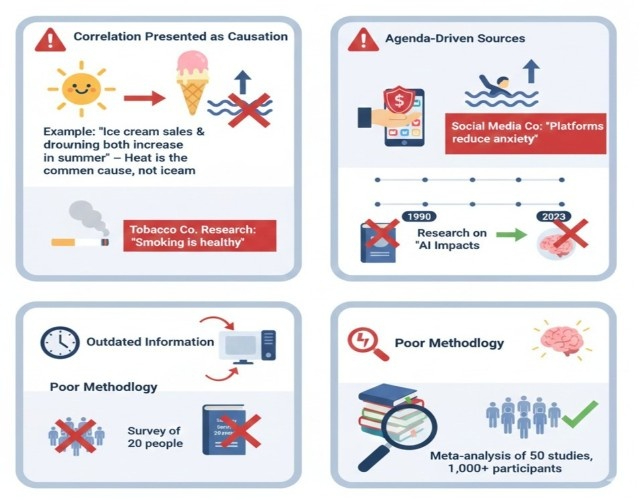

Correlation vs. Causation: The Critical Difference

This is where most students stumble.

Correlation means two things happen together.

Causation means one thing produces the other.

Classic example: Ice cream sales and drowning deaths both increase in summer. They correlate (happen together), but ice cream doesn't cause drowning. Hot weather causes both independently.

How to prove causation, not just correlation:

- Mechanism: Can you explain HOW A causes B? (Not just that they occur together).

- Timing: Does A consistently happen before B?

- Elimination: Have you ruled out other plausible causes?

If you can't answer these three questions, you're probably looking at correlation, not causation.

Avoid These Logical Fallacies

Post hoc reasoning:

- Assuming that because B followed A, A caused B.

- "I wore my lucky socks and passed the test, so lucky socks cause good grades".

- Reality: You studied, which caused good grades.

Oversimplification:

- Ignoring multiple contributing factors.

- "Poverty causes crime" (ignores education access, mental health resources, employment opportunities, community support).

- Better: "Poverty contributes to crime rates by limiting access to education and economic opportunities, though other factors also play significant roles."

Single-cause fallacy:

- Claiming complex outcomes have only one cause.

- Complex issues rarely have a single cause; acknowledge this complexity while maintaining focus.

How to Write Your Cause and Effect Essay Step by Step

Step 1: Choose Your Essay Focus

Strong topics have clear, provable causal relationships, supported by available research.

- What makes a good topic:

1. Clear cause and effect connection (not just correlation).

2. Appropriate scope (not too broad, like "effects of technology," or too

narrow, like "effects of eating three blueberries").

3. Available credible sources for evidence.

4. Personal interest to keep you engaged.

Red Flags

- Controversial causation: Topics where experts fundamentally disagree on whether causation exists are difficult for student essays. You'll spend all your time arguing that the relationship exists rather than analyzing it.

- Purely personal topics: "Effects of my parents' divorce on my life" has no research sources. "Effects of parental divorce on children's academic performance" has abundant research. Make topics researchable.

- Overdone topics: "Effects of social media" appears in thousands of student essays. If you choose a common topic, find a fresh angle: "Effects of social media algorithms on political polarization" is more specific and interesting than generic "social media effects."

- Topics requiring specialized expertise: Avoid highly technical topics unless you have the background. "Effects of quantum entanglement on particle behavior" requires physics expertise that most students lack

Still deciding? Browse 250+ vetted cause and effect essay topics across categories like psychology, environment, technology, health, and social issues. Each has clear causality and research availability.

Step 2: Research Thoroughly

Cause and effect essays demand credible evidence; you're explaining real relationships, not opinions.

What you need:

- 7-10 credible sources minimum.

- Peer-reviewed studies showing causation (not just correlation).

- Statistics from reputable organizations.

- Expert testimony from qualified professionals.

- Case studies or documented examples.

Research strategy:

- Start with academic databases (JSTOR, Google Scholar, PubMed).

- Look for studies that explain mechanisms (HOW X causes Y).

- Note compelling statistics and quotes.

- Document sources immediately to avoid scrambling later.

Research Red Flags

Remember: If you can only find sources showing correlation, not causation, reconsider your topic.

Remember: If you can only find sources showing correlation, not causation, reconsider your topic.

Step 3: Craft Your Thesis Statement

Your thesis must clearly state the cause-and-effect relationship you're examining.

Weak: "This essay discusses social media and mental health."

Problem: Doesn't identify the relationship.

Better: "Social media use affects teen mental health."

Problem: Vague, doesn't specify how.

Strong: "Excessive social media use (3+ hours daily) leads to increased anxiety, disrupted sleep patterns, and reduced self-esteem among teenagers."

Why it works: Names a specific cause, identifies measurable effects, and shows a clear relationship

Thesis formula: [Specific cause] leads to/results in/produces [specific effect(s)] because [brief mechanism/reason].

Testing Your Thesis

Ask "So what?": If the answer isn't obvious from your thesis, revise to make the significance clearer.

Ask, "Can I prove this?": Do you have adequate evidence for every element claimed? If you can't support part of your thesis, narrow it.

Ask "Is this specific enough?" Could someone write a completely different essay with the same thesis? If yes, add more specificity.

Step 4: Construct an essay framework

Don't skip this. Outlines save time during drafting and ensure logical organization.

Your outline should include:

- Introduction (hook, context, thesis).

- Structure choice (block or chain).

- 3-4 main body points (causes or effects).

- Evidence assigned to each point.

- Transition planning between sections.

- Conclusion strategy.

Spend 20% of your total writing time on the outline. For a 1,500-word essay written in 5 hours, that's 1 hour outlining. Worth it.

READY TO HAND IT OFF?

Professional writing assistance tailored to your needs

- Expert writers who understand causation

- Properly structured and cited

- Delivered on your deadline

- Original work with zero plagiarism

Unlimited revisions until you're satisfied.

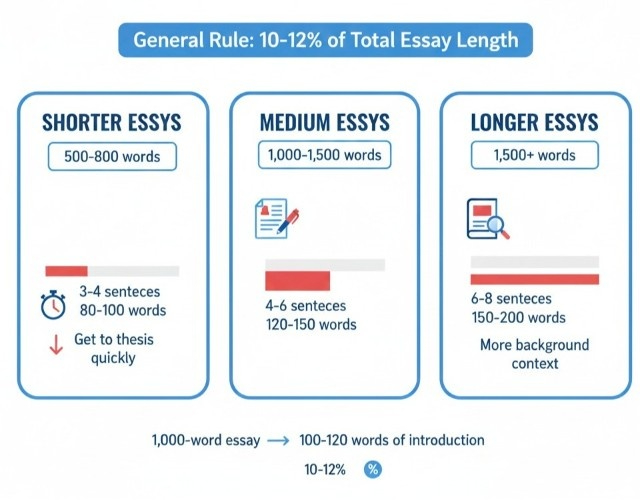

Order NowStep 5: How to start a Compelling Introduction

Your introduction determines whether readers continue or quit. In academic settings, instructors read the whole essay regardless, but strong introductions earn goodwill that benefits you during grading.

Introduction Components

Hook (1-2 sentences): Open with something that grabs attention and establishes relevance.

Background information (2-3 sentences): Provide necessary context for readers to understand your topic. Define key terms if needed, establish the current situation, or provide a brief relevant history.

Keep the background concise. Don't write a history chapter; give just enough context for your thesis to make sense.

Thesis statement (1 sentence): End your introduction with your thesis. This placement creates a clear transition into your body paragraphs and tells readers exactly what your essay will argue.

Introduction Length

Step 6: Develop Strong Body Paragraphs

Body paragraphs are where you prove your thesis. Each paragraph should examine one cause or effect with evidence and analysis.

Topic sentence: State what this paragraph will prove and how it connects to your thesis. Make it specific.

- Weak: "Social media has effects."

- Strong: "Beyond academic impacts, sleep deprivation significantly compromises immune system function among college students."

| Evidence 1 (2-3 sentences): Present your first piece of supporting evidence, a statistic, research finding, expert quote, or documented example. Cite your source. |

| Analysis (2-3 sentences): Explain how this evidence proves your point. Don't assume connections are obvious. Explicitly state: "This demonstrates that [cause] leads to [effect] because..." |

| Evidence 2 (2-3 sentences): Present additional supporting evidence from a different source or of a different type. One statistic plus one example is stronger than two statistics from the same study. |

| Analysis (2-3 sentences): Explain how this second piece of evidence further supports your claim. |

| Significance (1-2 sentences): Address "so what?" Why does this cause or effect matter? What are the implications? |

| Transition sentence (1 sentence): Connect this paragraph to what comes next. Preview the next point while wrapping up the current one. |

Paragraph Length Guidelines

Aim for 150-200 words per body paragraph (roughly 8-12 sentences). Paragraphs shorter than 100 words often lack sufficient development. Paragraphs longer than 250 words should usually be split; they're trying to cover too much.

Each paragraph should focus on ONE main idea. If you're discussing Effect 1 and Effect 2 in the same paragraph, split them. Readers struggle to follow paragraphs that juggle multiple points simultaneously.

Struggling with the writing process? Our reliable essay writing service delivers polished essays from research through the final draft. Hand it off to experts.

Evidence Integration

Use signal phrases:

Introduce evidence with phrases that establish credibility:

|

Various evidence types:

Don't rely solely on statistics or solely on examples. Mix:

|

Cite consistently: Every piece of evidence from a source needs a citation. Use your required format (MLA, APA, Chicago) consistently throughout.

Pro Tip: Transitions are the bridges connecting your ideas. Strategic transition use guides readers through your logic while reinforcing cause-and-effect relationships.

Step 7: How to Write a Cause Effect Essay Conclusion (End your essay with an impact)

Rephrase your main argument in fresh language. Do not repeat the introduction word-for-word. Briefly connect your key causes or effects, showing how they relate or build on each other; don’t simply list them. Answer “so what?” Explain why this cause-and-effect relationship matters and what its implications are. End with a strong final line that calls for action or poses a thoughtful question.

How to Organize a Cause and Effect Essay

Two proven organizational approaches work for cause-and-effect essays: block structure and chain structure. Your choice depends on your topic and how causes/effects relate to each other.

Block Structure (Grouped Organization)

How it works: Group all causes together, then all effects together (or vice versa). Each section is distinct and complete.

Best for:

- Topics where causes and effects don't directly connect to each other.

- Effect-focused or cause-focused essays.

- Shorter essays (500-1,000 words).

When to use: If your causes are independent reasons for one result, or your effects are separate outcomes of one cause, block structure keeps things clear and organized.

Chain Structure (Sequential Organization)

How it works: Alternate between causes and effects, showing how each effect becomes the next cause in a domino sequence.

Best for:

- Causal chain essays where events trigger each other.

- Topics with clear sequential relationships.

- Longer, more complex essays (1,500+ words).

Need a structured template? Our cause and effect essay outline guide provides fillable templates for both structures with step-by-step instructions.

Common Mistakes and How to Fix Them

Mistake 1: Confusing Correlation with Causation

- The problem: Claiming that something causes another thing just because they occur together.

- Example: "Video game sales increased while violent crime decreased, so video games reduce crime."This ignores dozens of other factors affecting crime rates

- The fix:

1. Explain the mechanism: HOW does X cause Y?.

2. Check timing: Does X consistently precede Y?

3. Eliminate alternatives: What other factors could explain Y?

4. Use qualifying language: "contributes to," "is one factor in," "plays a role in".

Mistake 2: Oversimplifying Complex Issues

- The problem: Treating multifaceted problems as if they have single causes.

- Example: "Poverty causes crime"; Ignores education access, employment opportunities, mental health resources, and community support systems

- The fix:

1. Acknowledge complexity: "Poverty contributes to higher crime rates by limiting..."

2. Focus on 3-4 significant factors rather than claiming one absolute cause.

3. Use phrases like "one major factor," "primarily results from," "among the key causes."

Mistake 3: Poor Organization

- The problem: Jumping randomly between causes and effects without a clear structure.

- The fix:

1. Choose a block or chain structure before outlining.

2. Stick with your choice throughout.

3. Use transition sentences: "Beyond these social factors, economic conditions also contribute..."

4. Make it obvious whether each paragraph discusses a cause or an effect.

Mistake 4: Weak Evidence

- The problem: Making claims without credible support.

- Example: "Everyone knows social media causes anxiety." Who is "everyone"? Where's the data?

- The fix:

1. Every major point needs 2-3 pieces of evidence.

2. Statistics from reputable studies.

3. Expert testimony from qualified professionals.

4. Documented case studies or examples.

5. Peer-reviewed research findings.

Mistake 5: Ignoring Counterarguments

- The problem: Failing to address alternative explanations.

- Example: "Social media causes depression" without acknowledging that correlation isn't necessarily causation.

- The fix:

1. Acknowledge alternative explanations.

2. Explain why your focus is most significant.

3. Use phrases like "while other factors contribute..

Tips for Stronger Cause and Effect Essays

| Tip | What It Means | How to Apply It |

|---|---|---|

| Start with “Why” and “So What” | Go beyond surface-level claims | Ask how a cause creates an effect and why the effect matters. |

| Use the PEEL paragraph method | Ensure structured, complete paragraphs | Point leads to Evidence, which leads to Explanation, and then links back to the thesis or next idea. |

| Balance depth and breadth | Quality over quantity | Analyze 3–4 causes or effects deeply rather than listing many superficially. |

| Use concrete examples | Make abstract ideas tangible | Support claims with studies, statistics, or real-world examples. |

| Address alternative explanations | Strengthen credibility | Acknowledge other causes and explain why your focus matters more. |

| Vary transition words | Improve flow and clarity | Rotate cause indicators (stems from, arises from) and effect indicators (leads to, produces, triggers). |

Free Cause and Effect Essay Resources

We've created comprehensive downloadable resources to support every stage of your writing process to translate the strategies in this guide into practical, actionable templates you can use immediately.

Cause and Effect Essay Writing Checklist

A comprehensive checklist covering every phase from topic selection through final revision. Use this to ensure you haven't missed critical steps.

Includes:

- Pre-writing phase checklist

- Research and evidence gathering checklist

- Drafting phase checklist

- Revision checklist (content, organization, language, technical)

- Final submission checklist

Cause and Effect Essay Grading Rubric

Understand what professors look for when grading cause and effect essays. Use this for self-evaluation before submission.

Includes:

- Thesis statement criteria

- Evidence and support requirements

- Organization and structure expectations

- Language and mechanics standards

- Point breakdown showing the weight of each element

OVERWHELMED BY THE WORKLOAD?

Skip the stress. Our professional writers handle everything so you can submit with confidence.

- 100% original, human-written

- Full confidentiality guaranteed

- Subject experts in every field

- On-time delivery guaranteed

Zero AI. Zero stress. Just results.

Order NowThe Bottom Line

Cause and effect essays develop critical thinking by teaching you to trace relationships between events, distinguish genuine causation from coincidence, and explain complex connections with evidence and logic.

Master the fundamentals, understanding causation types, choosing appropriate structure, backing claims with credible research, and organizing logically, and you'll write essays that don't just inform but genuinely help readers understand how the world works.

The systematic approach works: choose a topic with clear causality, research thoroughly to establish mechanisms, create a detailed outline using block or chain structure, write with strong evidence for every claim, and revise to ensure logical flow throughout.

-19317.jpg)

-19320.jpg)