If you are still confused, you can buy an argumentative essay from our reliable essay writing service.

What is an Argumentative Essay?

Argumentative Essay Definition: This essay's meaning is to take a clear stance on a debatable issue and prove your position using evidence, logic, and reasoning. That's it.

Think of it like being a lawyer in court, except your jury is your professor, and the verdict is your grade.

Here's what makes argumentative essays different:

You're not just sharing your opinion ("I think dogs are better than cats"). You're building an intellectual case with research, data, and logical reasoning to convince skeptics who might completely disagree with you.

The goal isn't to make people feel emotional or inspired; that's persuasive writing. The goal is to make them think, "Okay, based on the evidence, this position makes sense."

Characteristics of Argumentative Essays

- Presents a clear, debatable position through a strong thesis statement

- Focuses on logical reasoning rather than personal opinion or emotion

- Uses credible evidence such as facts, statistics, examples, and expert opinions

- Maintains a formal, objective, and persuasive tone throughout

- Follows a clear and organized structure (introduction, body paragraphs, conclusion)

- Addresses opposing viewpoints to show balance and critical thinking

- Refutes counterarguments with logic and supporting evidence

- Uses transitions to ensure smooth flow between ideas

- Supports claims with analysis, not just description

- Aims to persuade readers by presenting a well-reasoned essay

Why Professors Make You Write These

Your professor isn't torturing you for fun. Argumentative essays develop skills you'll actually use:

- Critical thinking: Analyzing issues from multiple angles before forming opinions

- Research skills: Finding credible sources and spotting bullshit

- Clear communication: Making complex ideas simple and compelling

- Professional writing: Legal briefs, business proposals, policy papers, they're all arguments

The students who master this are the ones who later write proposals that get funded, emails that get responses, and presentations that change minds.

Short on Time?

If your deadline's breathing down your neck and you need this done RIGHT! You are at right place.

- Delivers custom argumentative essays

- Zero AI

- Zero plagiarism

- Unlimited revisions

Every essay is researched, cited, and written by actual experts in your subject area.

Order NowArgumentative vs. Persuasive: What's the Difference?

Students confuse these all the time, but they're not the same:

Argumentative Essay | |

Logic and evidence-based | Can use emotion and appeals |

Must address opposing views | Can ignore counterarguments |

Formal, academic tone | Can be informal or passionate |

Goal: Prove your position with facts | Goal: Convince using any means |

In school, when your professor says "argumentative," they want logic and research not emotional stories about your grandma.

When assigned an essay, check your rubric carefully. If it requires addressing counterarguments and citing academic sources, you're writing an argumentative essay. If it encourages emotional appeals and personal conviction, it's persuasive.

The Core Components of an Argumentative Essay

Before we get into the writing process, understand these five non-negotiables. Get these right, and you're already ahead of 80% of students.

1. A Clear, Specific Thesis Statement

Your thesis statement is the backbone of your entire essay, a single sentence that declares your position and previews your main supporting reasons.

A strong thesis is specific, debatable, and defensible.

Weak: "Social media has pros and cons." (That's not an argument it's an announcement)

Strong: "While social media enhances connectivity, its algorithm-driven content significantly increases teen anxiety and should face mandatory transparency requirements." (Clear position + specific reasons)

Notice the difference? The strong thesis takes a clear position and hints at the reasoning to come. Your thesis appears at the end of your introduction and guides every paragraph that follows.

2. Well-Researched, Credible Evidence

You can't just say "studies show" or "experts agree." You need specific evidence:

- Statistical data from reputable sources (government agencies, peer-reviewed studies)

- Expert testimony from qualified professionals

- Real-world examples that illustrate your points

- Logical reasoning that connects evidence to your claim

Source quality matters enormously. Prioritize: Peer-reviewed journals, .edu and .gov websites, Academic books, Established publications

| Avoid: Wikipedia, random blogs, obviously biased websites. |

3. Logical Organization

Your arguments should flow naturally, building a cumulative case for your position. Each body paragraph focuses on one main idea, explained thoroughly before moving to the next.

The organizational model you choose (more on this below) provides the framework for arranging your claims and evidence.

4. Counterargument + Refutation

This is what separates A papers from C papers. You must:

1. Acknowledge the opposing viewpoint fairly

2. Explain why that counterargument exists or seems valid

3. Refute it with stronger evidence or logic

Example:

"Critics argue that social media helps teens stay connected. While this benefit exists for some users, Stanford research shows that 73% of heavy social media users report feeling more isolated despite increased digital connections suggesting that quality of interaction matters more than quantity."

Ignoring counterarguments makes you look naive. Addressing them shows critical thinking and strengthens your credibility.

5. Formal Academic Tone

Write in third person. Avoid contractions. Eliminate slang. Remove emotional language.

Instead of: "I think social media is terrible for kids."

Write: "Research indicates social media correlates with increased anxiety among adolescents."

Your tone should be confident but not arrogant, assertive but not aggressive. Let your evidence speak for itself.

The 3 Main Argumentative Essay Types (And When to Use Each)

Not all arguments are built the same way. Here are the three proven approaches, and how to pick the right one:

1. Classical (Aristotelian) Model

Best for: Traditional academic essays, receptive audiences, clear-cut issues

This is the oldest approach, developed by Aristotle in ancient Greece. It's straightforward and familiar most high school essays follow this model.

When to use: Most general "write an argumentative essay" assignments. It's the safest default when your professor doesn't specify a model.

Key characteristics:

- Uses ethos (credibility), pathos (emotion), and logos (logic)

- Presents your arguments first, then addresses opposition

- Straightforward and easy to follow

2. Toulmin Model

Best for: Complex policy debates, scientific controversies, ethical dilemmas

Developed by British philosopher Stephen Toulmin, this analytical model breaks arguments into six logical components: claim, grounds (evidence), warrant (reasoning), backing, qualifier (limitations), and rebuttal.

When to use: College-level writing on topics like climate policy, healthcare reform, AI regulation anything requiring a sophisticated logical breakdown.

Key characteristics:

- Highly analytical and systematic

- Acknowledges limitations of your claim

- Best for nuanced issues without absolute answers

3. Rogerian Model

Best for: Highly controversial topics, hostile audiences, seeking compromise

Created by psychologist Carl Rogers, this diplomatic approach emphasizes finding common ground. You present opposing views fairly first, identify shared values, and then introduce your position as complementary rather than oppositional.

When to use: Polarizing topics like gun control, abortion rights, immigration policy, and anything where both sides have legitimate concerns.

Key characteristics:

- Most diplomatic and respectful approach

- Reduces hostility by validating opposing concerns

- Proposes compromise solutions

Quick Decision Guide

- Clear-cut topic + receptive audience = Classical

- Complex issue requiring nuanced analysis = Toulmin

- Controversial topic + divided audience = Rogerian

Most college essays use Toulmin or Classical models. Rogerian requires more sophistication and works best when genuinely seeking compromise rather than total victory. Want detailed breakdowns of each model with full explanations? Check our complete guide to argument types.

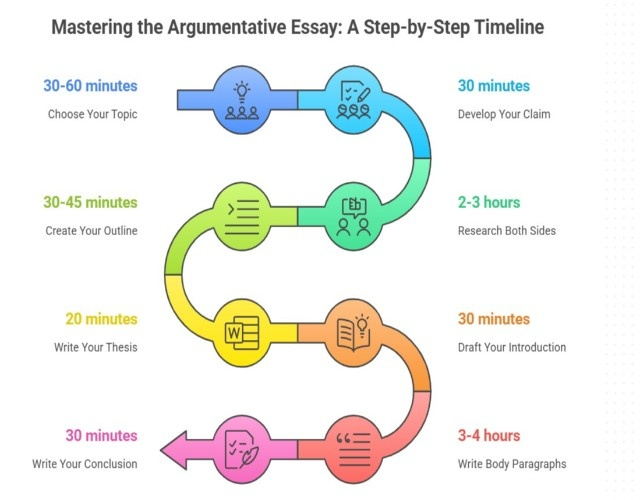

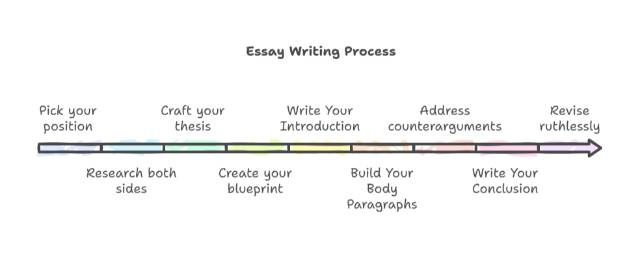

How to Write an Argumentative Essay: Step by Step Process

Alright, let's get into the actual writing. This process takes 8-12 hours spread over 3-5 days for optimal results. Don't try to cram it all into one night you'll hate the result.

Step 1: Pick Your Side and Develop Your Claim

Once you have your topic (need ideas? Browse our list of 350+ argumentative essay topics, and decide your specific position.

What exactly are you arguing? Your claim should be clear, specific, and defensible with evidence.

- Vague claim: "Social media affects teenagers."

- Specific claim: "Social media platforms should face mandatory transparency requirements for users under 18."

This isn't your final thesis yet; that comes later. This is your core position that will guide your research.

Step 2: Research Both Sides Thoroughly

This is your most time-intensive step, but it's crucial. How to start an argumentative essay? Spend 60-90 minutes gathering 5-8 credible sources.

Here's the key: Research BOTH sides, not just your position.

Why research the opposition?

- You'll need to refute counterarguments later

- Understanding opposing views makes your argument stronger

- You might discover your initial position was wrong (it happens)

Where to find credible sources:

- Google Scholar for peer-reviewed studies

- Government databases (.gov sites) for statistics

- University libraries and academic journals

- Established news outlets for recent developments

Red flags for unreliable sources:

- No author listed

- Overly emotional or biased language

- No citations for their own claims

- Published by unknown organizations

Pro tip: Create a two-column document while researching: Left column: "Evidence Supporting My Position". Right column: "Evidence Opposing My Position." This organization will save you hours when you start writing.

Step 3: Craft Your Thesis Statement

Your thesis is the most important sentence in your entire essay. It states your position and previews your main supporting reasons.

Formula:

"[Position] because [Reason 1], [Reason 2], and [Reason 3]."

| Example: "High schools should start no earlier than 8:30 AM because adolescent biology requires later sleep patterns, early start times correlate with decreased academic performance, and delayed schedules improve student mental health outcomes." |

Your thesis should:

- Take a clear, specific stance

- Be debatable (reasonable people can disagree)

- Include your main reasons

- Appear at the end of your introduction

Step 4: Create Your Blueprint

Before you write a single paragraph, create a roadmap. This 30-45 minute investment prevents hours of frustration later.

Your blueprint should map out:

Introduction (hook, background, thesis)

Body paragraph 1 (first main argument + evidence)

Body paragraph 2 (second main argument + evidence)

Body paragraph 3 (third main argument + evidence)

Body paragraph 4 (counterargument + refutation)

Conclusion (synthesis + implications)

Need argumentative essay help? Download our free, ready-to-use argumentative essay templates for all three argument models.

Step 5: Start Writing (How to Write Your Introduction?)

Your introduction has three jobs:

1. Hook the reader

Start with something that grabs attention:

- Surprising statistic: "70% of high school students report chronic sleep deprivation."

- Provocative question: "What if your school schedule was damaging your brain development?"

- Relevant scenario: "Jake fell asleep during his calculus exam for the third time this semester."

2. Provide context

Give readers the background they need. What's the issue? Why does it matter? What's currently happening?

Keep this brief, 2-3 sentences max. You're setting the stage, not writing the whole play.

3. Present your thesis

End your introduction with your clear, specific thesis statement.

Length: 150-200 words total.

Step 6: How to Build Your Body Paragraphs

Each body paragraph should follow this proven pattern:

Topic Sentence: State the main point of this paragraph clearly. Evidence: Present your research, statistics, or expert testimony. Analysis: Explain how your evidence supports your argument. Don't assume readers will connect the dots do it for them. Transition: Connect to your thesis and lead into the next paragraph. |

Length: This is your longest section plan for 3-4 hours of writing.

Critical tips:

- One main idea per paragraph

- Cite every claim with proper format (MLA, APA, Chicago whatever your professor requires)

- Use transition words: "Furthermore," "In addition," "However," "Consequently"

- Aim for 200-300 words per paragraph

Step 7: Address Counterarguments

This is typically your last body paragraph before the conclusion, and it's what makes your argument bulletproof.

The formula:

1. State the counterargument fairly

"Opponents argue that later school start times would disrupt bus schedules and extracurricular activities."

2. Acknowledge any validity

"This concern is understandable given that many districts share buses across multiple schools."

3. Refute with stronger evidence

"However, districts that have implemented later start times, such as Seattle Public Schools, report that logistical challenges were resolved within one academic year through staggered schedules, while academic and mental health benefits persisted long-term."

Pro tip: Address the STRONGEST counterargument, not the weakest. Taking down a strong opposing point makes your position look unshakeable. Attacking a weak strawman makes you look intellectually dishonest.

Still Stuck? We're Here to Help

If you're juggling three papers due the same week. Our writers know how to:

- Find and integrate credible, current research

- Build arguments that actually convince (not just sound good)

- Address counterarguments without weakening your position

- Meet any citation style requirements (APA, MLA, Chicago, Harvard)

Thousands of students have trusted us with their most important assignments. You can too.

Order NowStep 8: Conclude Your Essay (How to Write Your Conclusion)

Your conclusion should NOT just repeat everything you already said. That's boring and lazy.

Instead:

1. Restate your thesis in fresh language

Don't copy-paste from your introduction. Say the same thing differently.

"Aligning school schedules with adolescent biology isn't a luxury it's a necessity for student success."

2. Synthesize your main points

Show how your arguments work together. Don't just list them connect them.

"By understanding teenage sleep biology, recognizing the academic costs of sleep deprivation, and acknowledging the mental health crisis affecting students, the case for later school start times becomes undeniable."

3. Explain broader implications

Why does this matter beyond your essay? What are the real-world consequences?

"As we continue to demand more from students academically while ignoring their basic biological needs, we're not preparing them for success we're setting them up for burnout."

4. End with impact

Final thought, call to action, or provocative statement that sticks with readers.

"The question isn't whether we can afford to change school start times it's whether we can afford not to."

Length: 150-200 words.

Revision and Proofreading (Your Success Checklist)

First drafts are always rough. That's normal. Here's how to transform yours from "meh" to "damn, this is good":

Content revision (30 minutes):

- Does every paragraph support your thesis?

- Is your evidence credible and properly cited?

- Have you addressed counterarguments effectively?

- Do your transitions flow smoothly?

Line editing (15 minutes):

- Cut unnecessary words and filler phrases ("very," "really," "in today's society")

- Replace weak verbs with strong ones ("use" = "employ," "show" = "demonstrate")

- Vary sentence structure to maintain flow

- Check that your tone stays academic throughout

Proofreading (15 minutes):

- Grammar and spelling errors

- Citation format consistency

- Proper punctuation

- Formatting requirements (margins, font, spacing)

Pro tip: Read your essay aloud. Awkward phrasing and errors jump out when you hear them.

Use this checklist before submitting:

Thesis & Focus

- Thesis states a clear, debatable position

- Thesis includes main supporting reasons

- Every paragraph relates directly to thesis

Evidence & Research

- 5-8 credible sources cited

- Evidence is specific (not vague "studies show")

- All claims are properly cited

- Sources are recent and relevant

Argument Quality

- Each body paragraph has one main idea

- Counterarguments are addressed fairly

- Refutation uses evidence, not just opinion

- Logic is sound (no fallacies)

Writing Quality

- Tone is formal and academic (third person)

- Transitions connect ideas smoothly

- No grammatical or spelling errors

- Word count meets requirements

- Formatting follows assignment guidelines

Common Mistakes That Tank Your Grade (And How to Avoid Them)

Even strong writers make these errors when rushed or skipping steps. Recognize them so you don't repeat them.

Mistake #1: Choosing Non-Debatable Topics

Problem: Topics with only one reasonable position aren't argumentative they're factual.

Bad: "Smoking causes cancer" (established fact)

Good: "Should e-cigarettes face the same regulations as traditional tobacco?" (real debate)

Fix: If you can't identify strong opposing arguments, choose a different topic.

Mistake #2: Vague or Weak Thesis Statements

Problem: Weak theses fail to take clear positions.

Bad: "Social media has pros and cons."

Good: "While social media enhances connectivity, its algorithm-driven content significantly increases teen anxiety and should face mandatory transparency requirements."

Fix: Use the thesis formula: Position + Main Reasons. Be specific.

Mistake #3: Ignoring Counterarguments

Problem: Essays that don't address opposing views appear one-sided and naive.

Fix: Dedicate an entire paragraph to presenting and refuting the strongest counterargument. This demonstrates critical thinking and strengthens your credibility.

Mistake #4: Using Unreliable Sources

Problem: Wikipedia, random blogs, and obviously biased websites undermine your credibility.

Fix: Stick to peer-reviewed journals, .edu/.gov sites, academic books, and established publications. Your argument is only as strong as your evidence.

Mistake #5: Emotional Arguments Instead of Logical Ones

Problem: This isn't persuasive writing where emotional appeals belong.

Bad: "Clearly, anyone with a brain supports this policy."

Good: "Three independent studies demonstrate this policy reduces costs by 23% while improving outcomes."

Fix: Build intellectual cases with facts and data, not emotion and opinion.

Mistake #6: Poor Organization Without Planning

Problem: Skipping the planning phase leads to wandering arguments, repetition, and weak flow.

Fix: Always create a blueprint before drafting. Those 30 minutes you "save" cost you 2-3 hours fixing organizational problems later.

Mistake #7: Introducing New Arguments in Conclusion

Problem: Conclusions summarize existing arguments they don't open new debates.

Fix: If you discover a new point while writing your conclusion, it belongs in a body paragraph. Conclusions should feel like natural endings, not beginnings.

Stuck finding data for your argument? Our essay writing service has access to academic databases and knows exactly how to build research-backed cases that professors can't dismiss.

Free Argumentative Essay Resources & Templates

Master argumentative essay writing with our professionally designed resources. These tools have helped thousands of students improve thprofessionally designedeir grades and writing confidence.

Tools & Resources to Make This Easier

1. Evidence & Citation Tracker (PDF) Organized PDF for tracking sources, key evidence, and citations. Prevents plagiarism, keeps research organized, and makes drafting faster.

2. Thesis Statement Formula Guide (PDF) Five proven thesis templates with fill-in-the-blank versions. Includes 20 examples comparing weak versus strong thesis statements. Never struggle with thesis writing again.

3. Peer Review & Self-Editing Checklist (PDF) 30-point evaluation rubric organized by category: argument strength, evidence quality, organization, style, and mechanics. Use for self-editing or peer feedback sessions.

How to Use These Argumentative Resources

Start with the Topic Selection Worksheet to identify your perfect topic. Once chosen, use the Outline Template matching your argument model. Track your research with the Evidence Tracker. Draft your thesis using our Formula Guide. Study the Argumentative Essay Examples to see techniques in action. Finally, revise using the Peer Review Checklist.

HAND IT OFF TO THE EXPERTS

Thousands of students trust us to deliver essays that get the grades they deserve.

- Zero plagiarism, 100% original

- PhD-level analytical thinking

- Delivered on time, every time

- Full confidentiality guaranteed

Join 50,000+ satisfied students.

Order NowBottom Line

Writing a strong argumentative essay isn't about being naturally talented or having perfect writing skills from day one. It's about following a proven process:

Every strong essay you've ever read followed this same path. The difference between a B paper and an A paper usually isn't brilliance, it's thorough research, clear organization, and careful revision.

Start early. Follow the process. Trust your evidence.

You've got this.