Three Main Types of Argumentative Essays

Every effective argumentative essay follows a structural model that organizes claims, evidence, and reasoning. While all argumentative essays share common elements, clear thesis, supporting evidence, counterargument refutation, and logical organization, the three main types of arguments arrange these components differently to serve different rhetorical purposes.

1. Classical (Aristotelian) Model

What it is: The traditional persuasion structure used since ancient Greece.

How it works: You present your position clearly, defend it with evidence, address counterarguments, and conclude with a strong call to action.

Main components:

- Introduction: Hook + background + thesis

- Narration: Context and facts your reader needs

- Confirmation: Your main arguments with evidence

- Refutation: Address opposing views and explain why they're wrong

- Conclusion: Reinforce your position and call to action

When to use it:

- Your audience is neutral or already somewhat agrees with you

- The issue has a clear right/wrong answer

- You have strong evidence on your side

- Academic essays with traditional formats

Best for topics like:

- Should college be free?

- Is climate change caused by humans?

- Should the death penalty be abolished?

Why it works: Classical argumentation uses three persuasive appeals that Aristotle identified:

Ethos: Credibility (why should readers trust you?)

Pathos: Emotion (how does this affect people?)

Logos: Logic (what does the evidence prove?)

| Example scenario: You're writing about why public schools need more funding. Your audience (your professor and classmates) is generally reasonable. You present budget data, student outcomes, teacher testimonials, address the "but taxes!" objection, and conclude with a call for policy change. |

See complete Classical model examples showing how ethos, pathos, and logos integrate throughout.

Stuck turning your topic into a strong argument?

Our professional writers develop research-backed essays every day.

- Complete Confidentiality

- No AI, 100% Human Written

- on-time delivery

- Free Unlimited Revisions

Join thousands of satisfied students

Order Now2. Toulmin Model

What it is: A logic-based argument structure that breaks reasoning into six clear components.

How it works: You build your case systematically by showing how evidence connects to your claim through logical reasoning.

Main components:

- Claim: Your main argument (what you're trying to prove)

- Grounds: Evidence supporting your claim (data, facts, examples)

- Warrant: The logical connection between your evidence and claim

- Backing: Additional support for your warrant

- Qualifier: Words that limit your claim (usually, often, in most cases)

- Rebuttal: Exceptions or counterarguments you acknowledge

When to use it:

- Complex topics without absolute answers

- Scientific or policy debates

- Issues requiring analytical depth

- When you need to show sophisticated reasoning

Best for topics like:

- Should gene editing be allowed in humans?

- Do carbon taxes reduce emissions effectively?

- Is a universal basic income economically viable?

Why it works: The Toulmin model forces you to make your reasoning explicit. Instead of jumping from evidence to conclusion, you explain the logical pathway between them.

Example scenario: You're arguing that social media harms teen mental health.

|

Review our Toulmin outline template with detailed instructions for each component.

3. Rogerian Model

What it is: A consensus-building argument that emphasizes understanding opposing views before presenting your position.

How it works: You demonstrate genuine respect for the other side, find common ground, then introduce your position as a reasonable compromise.

Main Components:

- Introduction: Acknowledge the controversy without taking sides

- Opposing viewpoint: Present the other side fairly and respectfully

- Statement of understanding: Show you genuinely understand their concerns

- Your position: Introduce your view

- Statement of context: Explain when/why your position is valid

- Benefits to opposition: Show how your position addresses their concerns, too

When to use it:

- Highly polarized topics where people have strong emotions

- Hostile or defensive audiences

- Issues where compromise is possible

- When you need to build trust before persuading

Best for topics like:

- Should prayer be allowed in schools?

- Gun control legislation

- Abortion rights

- Immigration policy

Why it works: The Rogerian approach disarms defensive readers. By validating their concerns first, you make them more willing to consider your perspective.

Example scenario: You're writing about gun control for an audience that includes strong Second Amendment advocates. Instead of starting with "We need stricter gun laws," you begin: "Both sides of the gun debate share a fundamental goal: protecting innocent lives. Second Amendment advocates rightly worry about government overreach and personal safety. Gun control advocates legitimately fear preventable tragedies. These concerns aren't mutually exclusive." Then you introduce universal background checks as a middle ground that respects gun ownership while addressing safety concerns. |

Critical note: Rogerian arguments require genuine empathy. Readers detect fake respect. Only use this model when you can fairly represent both sides. Review our latest argumentative essay topics that fit for Rogerian model.

Complete Comparison of Types of Arguments

Understanding how different types of arguments help you select the right approach for your specific assignment. This comparison table highlights key distinctions across multiple dimensions.

| Factor | Toulmin | Classical (Aristotelian) | Rogerian |

|---|---|---|---|

| Developed By | Stephen Toulmin (1958) | Aristotle (384-322 BCE) | Carl Rogers (1970) |

| Best For | Complex policy issues | General academic essays | Controversial topics |

| Audience Type | Neutral/analytical | Receptive/neutral | Hostile/polarized |

| Primary Goal | Logical analysis | Persuasion through reason | Finding common ground |

| Structure | 6 components | 4 parts | 5 parts |

| Difficulty Level | Medium-Hard | Easy-Medium | Hard |

| Academic Level | College+ | High school+ | College+ |

| Overall Tone | Analytical, objective | Persuasive, confident | Conciliatory, diplomatic |

| Counter-argument | Rebuttal section | Refutation section | Presented first, fairly |

| Emotional Appeals | Minimal/none | Limited (pathos) | Minimal/none |

| Example Topics | Healthcare reform, climate policy | School uniforms, standardized testing | Abortion rights, gun control |

| Writing Time | 10-14 hours | 8-12 hours | 12-16 hours |

Key Takeaways from Comparison

Toulmin requires the most analytical thinking. You're breaking arguments into component parts like a scientist dissecting specimens. This model suits students comfortable with logic and comfortable analyzing rather than simply arguing.

Classical offers the most straightforward approach. Its familiar structure, introduction, arguments, refutation, and conclusion mirror what most students learned in high school. Choose Classical when your assignment doesn't specify a model, and you're addressing a general academic audience.

Rogerian demands the most sophistication and empathy. You must genuinely understand opposing viewpoints and present them fairly before introducing your position. This model takes the longest because diplomatic balance is harder to achieve than a simple assertion.

The controversy level of your topic provides the clearest selection guidance. Low controversy topics work fine with Classical. Medium controversy benefits from Toulmin's analytical depth. High controversy requires Rogerian's diplomatic approach to avoid alienating readers.

Stop Stressing. Start Submitting. Our professional writers craft essays that impress professors and earn top marks. Trusted by 50,000+ students worldwide

Types of Reasoning: Deductive vs. Inductive

Beyond structural models, arguments use two fundamental reasoning patterns:

Inductive Reasoning

Bottom-up logic: Start with specific observations, then build to a general conclusion.

Observation 1: Study A shows that minimum wage increases didn't reduce employment in Seattle

Observation 2: Study B shows similar results in San Francisco

Observation 3: Study C confirms the pattern in 15 other cities

General conclusion: Minimum wage increases don't significantly harm employment

Best for: Building new theories, establishing patterns from data, and scientific research

Deductive Reasoning

Top-down logic: Start with a general principle, then apply it to a specific case.

General principle: All humans need clean water to survive

Specific case: Rural communities in Flint lack clean water

Conclusion: Flint residents' health is at risk

Best for: Applying established principles, legal arguments, and mathematical proofs

Combining Both (Strongest Approach)

Most effective arguments use both reasoning types:

- Inductive establishment: "Multiple studies show higher minimum wages don't reduce employment" (observations = general principle)

- Deductive application: "Given that wage increases don't reduce employment, Seattle can safely raise its minimum wage" (principle = specific conclusion)

This combination provides empirical foundation (induction) plus logical force (deduction).

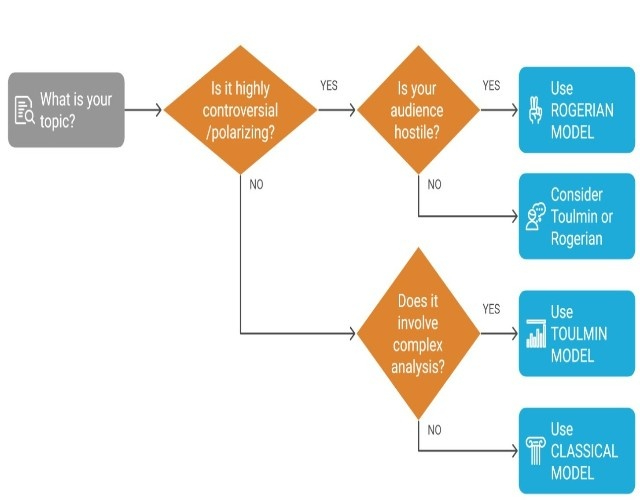

Choose Your Argument Model

Selecting the right model determines your essay's effectiveness before you write a word. Follow this systematic decision-making process to match models to your specific situation.

Visual Decision Tree

Can You Combine Types of Arguments?

Advanced writers sometimes blend elements from different types of arguments, but this requires skill to maintain coherence and consistency. Beginning and intermediate writers should master individual models before experimenting with combinations.

Possible Hybrid Approaches:

- Toulmin structure with Rogerian tone (analytical yet diplomatic)

- Classical structure with Toulmin's qualifier/rebuttal components (traditional persuasion with acknowledged limitations)

- Rogerian common-ground identification with Classical argumentation (establishing shared values before traditional arguments)

However, these hybrids risk confusing readers or creating structural inconsistency. Better to master one model fully than awkwardly blend multiple approaches.

Why Argument Types Matter

Understanding these argumentation methods transforms you from a one-approach writer into a strategic rhetorician who matches structure to situation.

Classical: Your reliable default. Traditional structure, balanced appeals, straightforward persuasion. Works for most academic essays.

Toulmin: Adds analytical depth. Shows sophisticated logical reasoning. Impresses professors who value rigorous analysis.

Rogerian: Builds consensus. Disarms hostile audiences. Essential for polarizing topics where trust matters.

Master these three structures, and you’re covered for nearly every argumentative essay. Still unsure where to start? Our reliable essay writing service knows how to work with all three models and can turn your ideas into a strong, well-structured paper.

Free Argumentative Models Downloadable Resources

Get Hours Back. Get a Better Essay Smart students outsource. Our writers deliver higher-quality work in less time. Zero AI. Zero stress. Just results.

Conclusion

Understanding the three main argument types: Toulmin, Classical, and Rogerian, transforms you from a one-approach writer into a strategic rhetorician who matches structure to situation. Each model offers distinct advantages for different topics, audiences, and goals.

Select your model strategically based on topic controversy, audience receptiveness, and assignment goals, and explore our complete argumentative essay guide for comprehensive coverage of all aspects.