What is an Informative Essay? Definition & Purpose

An informative essay means to inform the audience about something specific. Your job is to teach readers about a person, place, event, concept, or process without injecting your personal opinion. No persuading, no arguing, just presenting facts in a clear, organized way.

Teachers assign these because they test whether you can research a topic, understand it deeply, and explain it to someone else. It's less about what you think and more about whether you can make information stick.

Here's what makes an informative essay different:

- You're explaining photosynthesis, not arguing whether plants are important.

- You're describing the causes of World War I, not debating who was right.

- You're outlining how vaccines work, not convincing people to get vaccinated.

See the pattern? Information delivery, zero persuasion.

When you'll write these: High school research papers, college intro courses, standardized tests, pretty much anywhere teachers want to see if you can explain something without turning it into an opinion piece.

| The tricky part? Staying objective. Most people naturally slip into "I think" or "everyone should" territory. Informative essays require discipline present the facts, explain connections, and move on. No soapbox moments. |

DON'T DELIVER A BORING FACT SHEET.

Transform dry information into a compelling, reader-friendly, informative essay with our expert writers

- Engaging hooks and relatable examples

- Smooth integration of interesting facts

- A narrative flow that maintains interest

- Reader Engagement Formula

Be informative and interesting. Captivate your audience.

Get Started NowTypes of Informative Essay

| Type | Primary Purpose | Unique Example Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Process Analysis | Explains how to do something or how something works in a series of steps. | How the human body metabolizes caffeine from ingestion to excretion. |

| Cause and Effect | Examines the reasons behind an event and/or the consequences that result from it. | How the invention of the shipping container reshaped global economics and urban ports. |

| Compare & Contrast | Analyzes the similarities and differences between two or more subjects. | The problem solving approaches of computer science (algorithmic) and design thinking (human centric). |

| Definition | Provides an extended, in depth explanation of a complex concept or term. | Defining "quantum superposition" for a non scientific audience. |

| Problem Solution | Identifies a specific problem and proposes one or more viable solutions. | Mitigating light pollution in cities to protect nocturnal ecosystems and human health. |

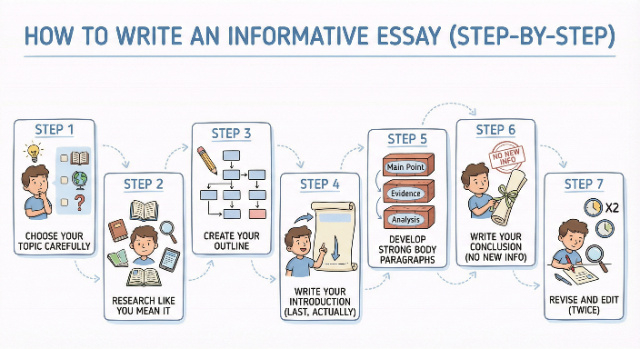

How to Write an Informative Essay: Complete 7 Step Process

Writing an informative essay isn't rocket science, but it does require a system. Here's the process that actually works.

Step 1: Choose Your Informative Topic Carefully

Pick something specific enough to cover thoroughly but broad enough to find solid research. "Climate change" is too massive for 1,000 words. "How solar panels convert sunlight to electricity" works perfectly.

What makes a good topic:

- Interesting to you (you're writing 1,500+ words on this)

- Has credible sources available (not just Wikipedia)

- Teachable in your word count (not too complex)

- Neutral enough to present objectively

| Red flags: Topics where you have strong opinions (hard to stay neutral), controversial subjects with limited factual consensus, or anything requiring specialized knowledge your audience won't have. |

Need a topic? Browse 240+ informative essay topics organized by category: science, history, technology, health, culture, current events, and more. Topics sorted by difficulty level so you can match your assignment requirements perfectly.

Step 2: Research and Gather Credible Sources

Good informative essays live and die by their sources. You need facts, statistics, expert quotes, and credible information, not random blog posts.

Where to look:

Where NOT to look: Random blogs, opinion pieces disguised as facts, Wikipedia as your only source (though it's fine for starting), anything without author credentials. |

Pro tip: Take notes with page numbers and URLs as you go. Scrambling for citations at 2am is nobody's idea of fun. Track everything now, thank yourself later.

Step 3: Create Your Informative Essay Sketch

Look, we know outlines feel like extra work. But here's the reality: 15 minutes outlining saves you 2 hours of staring at a blank screen, wondering what comes next.

Your outline should map every major point you'll cover, in order, with the evidence supporting each one. Think of it as your essay's GPS. You can adjust the route, but you need the destination mapped.

Need a ready to use structure? Our informative essay outline template gives you plug and play formats for every essay length. Fill in the brackets, hit save, and done.

Step 4: Write Your Introduction (Last, Actually)

Wait, write the intro last? Yes. Here's why: You don't know what you're introducing until you've written the body. Draft your body paragraphs first, then come back and write an intro that actually previews what you wrote.

When you do write it, include:

|

Step 5: Develop Strong Body Paragraphs

Each body paragraph should tackle one main subtopic. Don't try to explain everything about photosynthesis in one paragraph; break it into stages (light dependent reactions, Calvin cycle, etc.) and give each its own paragraph.

Structure each paragraph using PEEL:

- Point

- Evidence

- Explanation

- Link

PEEL Example for Informative Essay Body Paragraph:

- Point: "Solar panels convert sunlight through photovoltaic cells."

- Evidence: "Each cell contains semiconductor materials that release electrons when hit by photons."

- Explanation: "This flow of electrons creates direct current electricity."

- Link: "Once generated, this DC electricity must be converted for home use."

Common mistake:

|

Check out our informative essay examples with 10 annotated samples showing exactly how strong essays work. Middle school to college level, fully annotated to highlight what makes each one effective.

DROWNING IN SOURCES FOR YOUR INFORMATIVE ESSAY?

We synthesize the research into a clear, coherent, and insightful paper.

- Credible source synthesis and summarization

- Accurate data interpretation and presentation

- Flawless citation of all integrated information

- Research Synthesis Service

From information overload to elegant clarity. We connect the dots.

Order NowStep 6: Write Your Conclusion (No New Info)

Your conclusion restates your thesis, synthesizes your main points, and gives readers a clear takeaway. What it does NOT do: introduce new information, include new evidence, or start a new argument.

Three part structure:

|

Step 7: Revise and Edit (Twice)

- First pass: Content and structure. Does everything flow logically? Are your explanations clear? Does each paragraph support your thesis? Hack away anything unnecessary.

- Second pass: Grammar and mechanics. Sentences too long? Punctuation correct? Consistent tense? This is where you polish.

Better yet: Read it out loud. Your ears catch what your eyes miss. If you stumble reading it, your reader will stumble too.

Don't: Introduce new evidence, start discussing new subtopics, end with weak phrases like "in conclusion" or "as you can see," or make your conclusion longer than your intro.

How To Start An Informative Essay

A well crafted introduction, typically spanning 4-6 sentences, builds a foundation of knowledge upon which the rest of your essay will expand. It should intrigue the reader while remaining factual and focused, ensuring they know exactly what to expect from the information you are about to present.

1. Crafting an Effective Hook

Begin with an engaging sentence that captures attention and broadly relates to your topic.

- Use a Startling Statistic: "Approximately 91% of plastic waste is not recycled, highlighting a global management crisis."

- Pose a Relevant Question: "What if the key to solving urban traffic congestion lies not in building more roads, but in the behavior of ants?"

- Offer a Concise, Intriguing Fact: "The human brain generates enough electrical power to light a small lightbulb."

- Provide a Brief, Vivid Scenario: "Imagine a network of highways, not for cars, but for trillions of microscopic messages constantly traveling through your body."

2. Providing Necessary Background Context

Following the hook, offer 2-3 sentences that bridge the gap between your broad opener and your specific thesis.

- Define Key Terms: Briefly explain essential concepts your reader must understand.

- Give Historical or Social Context: Outline the origin or general significance of the topic.

- Establish the Topic's Scope: Narrow the focus from the general hook to the specific area your essay will cover.

3. Presenting a Clear Thesis Statement

The thesis statement is the critical final sentence of your introduction. It is a single, declarative sentence that encapsulates the core informative purpose of your entire essay.

- It Must Be Informative, Not Argumentative: State what you will explain, not what you will prove.

- It Should Outline the Essay's Structure: Act as a preview for the main points of your body paragraphs.

- Example: "This essay will explore the life cycle of a plastic product, examine the current failures in global recycling systems, and discuss innovative biotechnologies being developed to address plastic waste."

How To Conclude An Informative Essay

An effective conclusion moves from a restatement of the thesis to a broader consideration of the topic's implications, ensuring the reader understands both the details and the "big picture" value of what they have just learned.

1. Synthesizing Main Points

Begin your conclusion by revisiting your thesis in light of the evidence presented in the body paragraphs.

- Don't Repeat: Paraphrase your informative essay thesis statement using fresh language that reflects the depth of your essay's analysis

- Be Concise: Briefly synthesize the most important information from each main section, showing how they connect to form a coherent whole.

- Example: "As evidenced, the persistent issue of plastic waste stems from a complex combination of consumer habits, infrastructural limitations, and the material's own durability."

2. Restating the Thesis and Significance

Clearly reconnect your summarized points to the essay's core purpose to reinforce the reader's understanding.

- Articulate the "So What?": Answer why the information you presented matters. What is its broader importance or consequence?

- Reinforce the Central Idea: Emphasize the primary insight the reader should take away from your essay.

- Example: "Therefore, understanding the full lifecycle of plastics is crucial for developing effective solutions, moving beyond simple recycling to address the problem at its source."

3. Providing a Lasting Sense of Closure

End with a final, impactful sentence or two that gives the essay a sense of completion.

- Suggest Future Implications: Pose questions about the future direction of the topic based on the facts presented.

- Connect to a Broader Context: Link your specific topic to a wider human experience, ongoing scientific inquiry, or societal challenge.

- Offer a Final, Insightful Observation: Leave the reader with a thoughtful statement that underscores the topic's relevance.

- Avoid clichés like "in conclusion" or introducing brand new ideas.

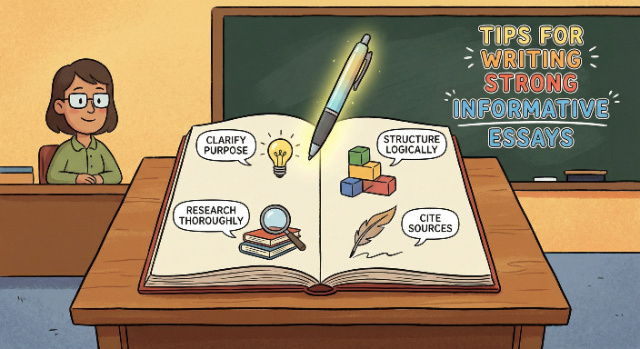

Tips for Writing Strong Informative Essays

Do This:

|

Don't Do This:

|

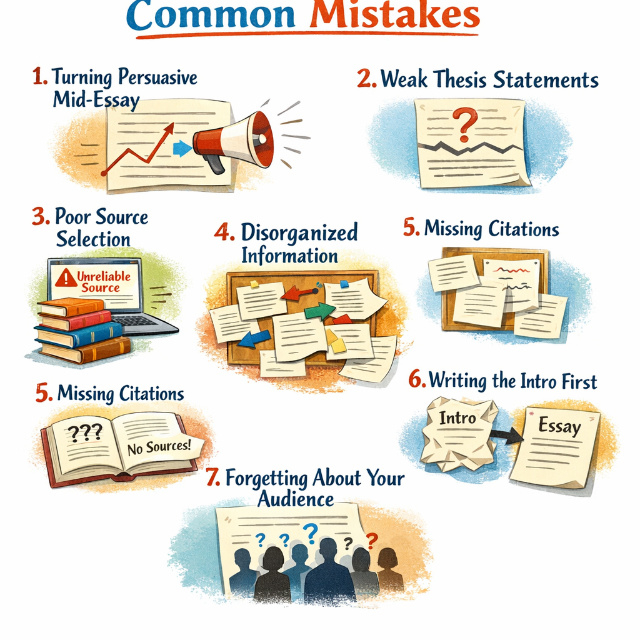

Common Informative Essay Mistakes to Avoid

1. Turning Persuasive Mid Essay

You start explaining climate change causes, then suddenly you're arguing why everyone should care. Stay in your lane. Informative = neutral information only.

2. Weak Thesis Statements

"This essay is about solar energy" tells readers nothing. "This essay explains how solar panels convert sunlight, their current efficiency rates, and their environmental impact." gives a clear roadmap.

3. Poor Source Selection

Three random blogs don't count as research. You need credible, authoritative sources, such as academic articles, expert authored books, and reputable institutions.

4. Disorganized Information

Bouncing between topics randomly loses readers fast. Organize logically, group related information, and use transitions to guide readers through your explanation.

5. Missing Citations

Every fact not considered common knowledge needs a citation. "

- Water boils at 100°C." Doesn't Need Citation

- "Solar panels operate at 20% efficiency." Needs Citation

6. Writing the Intro First

You don't know what you're introducing until you've written the body. Draft body paragraphs first, then write an intro that actually previews what you created.

7. Forgetting About Your Audience

Writing for experts when your audience is general readers (or vice versa) creates problems. Match your explanation depth to your audience's knowledge level.

Struggling with writing an informative essay? Our professional essay writing service specializes in informative essays across every subject, from explaining how vaccines work to breaking down cryptocurrency for beginners.

Downloadable Resource

Download this comprehensive workbook to master informative essay writing with a structured, step by step approach. This resource provides fillable templates, organizational frameworks, and revision checklists that guide you from initial research to final polish. You'll gain practical tools for thesis development, source integration, and objective writing that maintains clarity and academic rigor. Claim your free copy to transform complex information into compelling, well structured essays with confidence.

INFORMATIVE ESSAY DUE IN HOURS?

Get a well-researched, clearly written essay delivered on a tight deadline.

- Emergency drafting service

- Quick, accurate research on your topic

- Meets all length and formatting specs

- Urgent Delivery Experts

A quality informative essay, faster than you thought possible.

Get Started NowKey Takeaways: Mastering Informative Essays

Informative essays explain topics clearly using facts, not opinions. The structure is a straightforward intro with a thesis, body paragraphs with evidence, conclusion summarizing key points. Stay objective, cite credible sources, and organize information logically. Follow the steps, avoid common mistakes, and you'll write essays that actually teach readers something valuable.

-19941.jpg)