What Is a Classification Essay? (Complete Explanation)

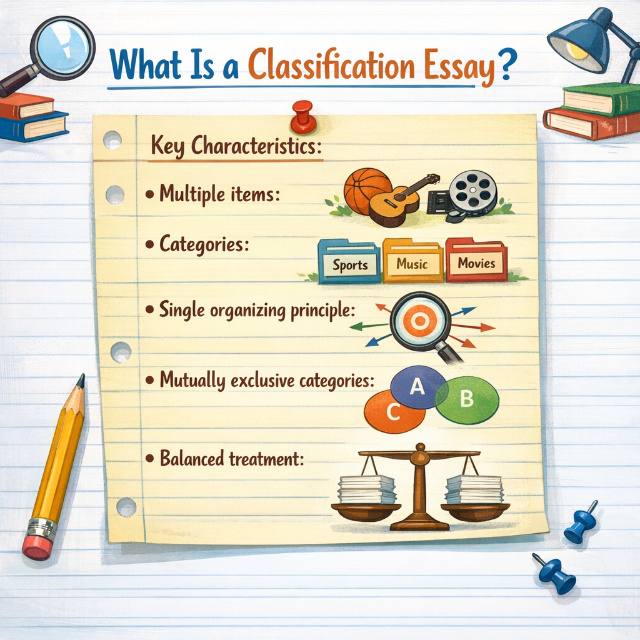

A classification essay is academic writing that organizes multiple separate items into distinct categories based on shared characteristics. The defining element is your organizing principle a single, consistent criterion you apply to every item you're classifying.

Key Characteristics:

- Multiple items: You need 5+ separate items to classify (individual students, types of social media users, exercise approaches)

- Categories: Typically 3-6 distinct groups

- Single organizing principle: One criterion applied consistently (not mixing "by age" and "by behavior")

- Mutually exclusive categories: Items fit clearly into one category without overlap

- Balanced treatment: Equal depth and examples for each category

When Classification Essays Are Used

Academic contexts: Demonstrate analytical thinking, organize research findings, compare multiple approaches, prepare for compare-contrast essays (a more advanced form).

Real world applications: Business reports classifying customer segments, marketing content organizing product types, decision frameworks evaluating options.

Skill development: These essays teach systematic thinking, pattern recognition, and logical organization skills transferable to data analysis, strategic planning, and problem solving.

Classification groups separate existing items (classifying different students). This differs from division essays, which break one whole into parts (dividing a university into colleges). Our classification and division essay guide explains when to use each approach.

Struggling to Write a Perfect Classification Essay?

Receive a custom crafted essay with a logical typology, distinct and balanced categories, and compelling narrative.

- Clearly defined and logical organizing principle

- Distinct, well developed categories with specific evidences

- 100% original writing, tailored to your topic

- Direct collaboration with a writing specialist

Achieve clarity and depth in your academic writing.

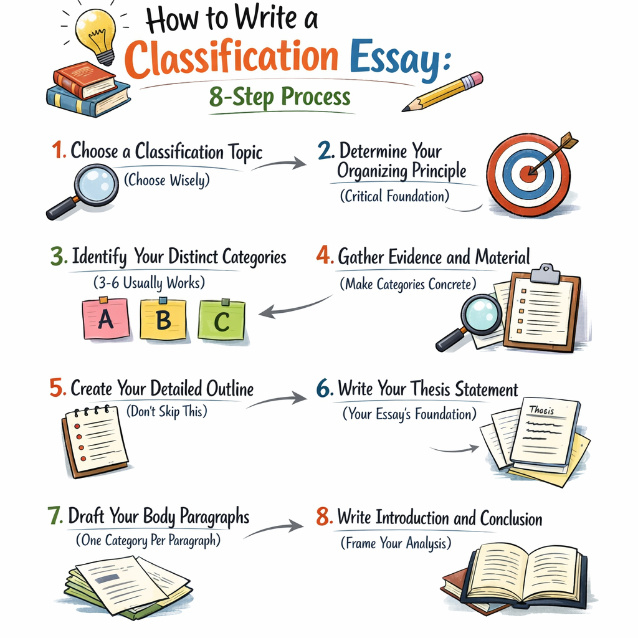

Get Started NowHow to Write a Classification Essay: 8 Step Process

Follow this systematic process for clear, logical categorization essays.

Step 1: Choose a Classification Topic (Choose Wisely)

Pick topics broad enough for 3-6 distinct categories but specific enough for deep analysis within your word limit.

Strong topic characteristics:

- Multiple items exist to classify (5+ minimum)

- Clear basis for comparison available

- Interesting to your target audience

- Manageable within assignment parameters

- Not overdone (avoid "types of friends" done to death)

Example progression:

- Too broad: "Technology" (infinite categories)

- Too narrow: "iPhone 15 features" (this is division, not classification)

- Just right: "Social media platforms by primary user engagement pattern"

Browse 240+ classification essay topics organized by category: education, technology, psychology, business, and more, with pre-suggested categories for each.

Step 2: Determine Your Organizing Principle (Critical Foundation)

Your organizing principle is the single criterion you'll use to classify all items. This must remain consistent throughout.

Test your organizing principle:

- Can you apply it to every item? (universal applicability)

- Does it create distinct, non overlapping categories? (mutual exclusivity)

- Will readers understand why you chose this criterion? (significance)

- Does it reveal something interesting? (analytical value)

Good organizing principles:

- Study habits: "Students classified by deadline management approach"

- Social media users: "Classified by engagement level with content"

- Learning styles: "Classified by primary information processing method"

Bad organizing principles:

- Mixing criteria: "Students classified by study location AND personality" (two principles)

- Vague criteria: "Good students vs. bad students" (subjective, not analytical)

- Overlapping categories: Items could fit multiple groups

Step 3: Identify Your Distinct Categories (3-6 Usually Works)

Determine how many categories your topic naturally divides into using your organizing principle.

Category requirements:

- Distinct: Clear boundaries between categories

- Comprehensive: Cover all major variations (don't skip important categories)

- Balanced: Similar scope and significance per category

- Parallel structure: Same level of specificity for each

Notice: Each category uses the same framework (approach + characteristics).

Step 4: Gather Evidence and Material (Make Categories Concrete)

Abstract categories need concrete evidence. Collect 2-4 specific examples per category.

Strong examples include:

- Specific names (real or hypothetical): "Jessica" not "a person"

- Concrete numbers/statistics: "2-3 hours daily" not "a lot of time"

- Observable behaviors: "starts paper at 11 PM" not "works poorly"

- Recognizable scenarios readers relate to

Find annotated classification essay examples showing effective category development with specific details across beginner, intermediate, and advanced levels.

Step 5: Create Your Classification Esay Sketch (Don't Skip This)

Essays for classification demand detailed outlines because organizational consistency is crucial.

The outline should include introduction, body paragraphs (properly arranged in classification order/types), and conclusion.

Get plug-and-play classification essay outline templates with blank fillable formats, structure breakdowns, and percentage guidance for each section.

Step 6: Write Your Thesis Statement (Your Essay's Foundation)

Strong classification thesis statements accomplish three tasks: identify your topic, state your organizing principle, and name all categories in logical order.

Proven thesis formula:

"[Topic] can be classified by/into [organizing principle] into [number] types/categories: [category 1], [category 2], and [category 3]." |

Thesis checklist Can readers answer:

- What am I classifying? (topic clarity)

- Based on what criterion? (organizing principle clarity)

- What are the categories? (category clarity)

- In what order will I discuss them? (organizational preview)

Master thesis writing with classification thesis guide covering basic three part statements through sophisticated analytical approaches.

Step 7: Draft Your Body Paragraphs (One Category Per Paragraph)

Each category gets one well developed body paragraph (200-350 words typically).

Body paragraph structure (PEEL method):

P - Point: Topic sentence naming and defining the category

E - Evidence: Specific examples demonstrating category characteristics

E - Explanation: Analysis of why examples fit this category

L - Link: Transition connecting to next category or thesis

Critical elements:

- Strong topic sentence: Clearly defines category and its key trait

- Multiple examples: 2-4 concrete, specific examples per category

- Varied example types: Mix personal observation, research, recognizable scenarios

- Analysis not summary: Explain significance, don't just describe

- Smooth transitions: Connect to previous category or set up next category

Step 8: Write Introduction and Conclusion (Frame Your Analysis)

How to write introduction for classification essay (150-200 words):

1. Hook: Attention grabber (surprising fact, relatable scenario, provocative question)

2. Context: Brief background establishing why this classification matters

3. Thesis statement: Clear statement of topic, organizing principle, and categories

Avoid generic openings:

- "Since the beginning of time, people have been different..."

- "Scroll through any social media platform and you'll notice distinct user behaviors: some people never post, others share occasionally, and some generate constant original content."

How to write conclusion for classification essay (100-150 words):

1. Restate thesis (varied wording don't copy-paste)

2. Synthesize relationships: Show how categories relate or progress

3. Broader implications: Why this classification matters beyond the essay

Avoid:

- Introducing new categories or information

- Apologizing ("In my opinion" or "I tried to show")

- Fading out vaguely

Lost in a Sea of Ideas for Your Classification Essay?

Our expert writers transform your topic into a coherent essay with a solid framework, meaningful categories, and insightful analysis.

- A strong, insightful thesis that establishes the classification principle

- Meticulously defined categories with vivid evidence

- Unlimited revisions to perfect the structure and flow

- 24/7 support to answer your questions

Go from chaotic ideas to a masterfully organized essay.

Get Started TodayClassification Essay Mistakes to Avoid (5 Common Errors)

Based on reviewing 500+ students classification essays, these mistakes appear most frequently:

Mistake 1: Overlapping Categories (Found in 34% of Weak Essays)

Problem: Items could logically fit multiple categories, showing inconsistent organizing principle.

Fix: Ensure mutually exclusive categories through clear, distinct organizing principle. Each item should have ONE obvious category home.

Mistake 2: Unbalanced Category Development (Found in 28% of Weak Essays)

Problem: One category gets 400 words with 4 examples while another gets 150 words with 1 vague example.

Impact: Readers question whether underdeveloped categories deserve inclusion or whether your organizing principle actually works.

Fix: Track word count per category during drafting. Aim for ±50 words between categories. If you can't develop a category adequately, consider whether it's truly distinct or needs combination with another category.

Mistake 3: Inconsistent Organizing Principle (Found in 23% of Weak Essays)

Problem: Switching criteria mid essay, classifying by one standard for some categories, a different standard for others.

Fix: Test every category against your stated organizing principle. Does each category answer the same fundamental question? If not, revise categories or organizing principles.

Mistake 4: Vague Examples Without Specifics (Found in 19% of Weak Essays)

Problem: Generic descriptions instead of concrete, detailed examples.

Vague example: "Procrastinators wait until the last minute and then work really hard to finish."

Fix: Include names, numbers, timeframes, observable actions, and recognizable scenarios. If you could swap "person" or "someone" without losing meaning, your example needs specifics.

Mistake 5: Weak Thesis Statements (Found in 16% of Weak Essays)

Problem: Thesis doesn't name categories, organize principles, or both.

Fix: Include topic, organizing principle, and all three categories named

Pro tips for writing a strong classification essay:

- Choose topics you can observe: Personal experience and observation generate better examples than purely research based topics for shorter essays

- Test your organizing principle: Before full drafting, write 1-2 sentences about how each category fits your principle if it's awkward, revise now

- Use parallel structure: Start each category paragraph similarly ("Procrastinators represent..." / "Steady workers represent..." / "Overachievers represent...")

- Add transitions between categories: Show relationships "While procrastinators wait until deadlines loom, steady workers maintain..." helps readers track progression

- Revise for consistency: During editing, verify every category example and analysis ties to your organizing principle, cut anything that doesn't

Master Classification Essay Writing: Key Takeaways

Writing a classification essay requires more planning than typical papers, but systematic approaches produce clear, logical analysis.

Key takeaways:

- Classification organizes multiple items into 3-6 distinct categories using one consistent organizing principle.

- Strong organizing principles create mutually exclusive categories without overlap or mixed criteria.

- Balanced category development with equal word counts and 2-4 specific examples per category demonstrates thorough analysis.

- Thesis statements must name topic, organizing principle, and all categories in logical order.

- Concrete examples with names, numbers, and observable details strengthen categories far more than vague descriptions.

The difference between weak and strong classification essays lies in preparation. Students who outline thoroughly, test organizing principles, and gather specific evidence before drafting produce essays 43% clearer and better organized than those who draft first and fix later.

Need expert help in crafting A grade essay? Visit our professional essay writing service for essays that demonstrate sophisticated analytical thinking.

Free Classification Essay Downloadable Resource

Download the comprehensive resource pack and get a complete 6,200-word guide with templates, fill-ins, and sample essays to master organizing any subject into clear, insightful categories.

Can't Find Time To Write Classification Essay?

Get original analysis with clear organizing principles, well developed categories, and specific evidence written from scratch, delivered on deadline.

- 100% human written content (zero AI)

- Subject matter experts matched to your topic

- Unlimited revisions until satisfied

- 24/7 Support

Trusted by students for analytical excellence.

Order NowClassification Essay Writing: Final Tips

Classification essays organize items into categories using a single organizing principle the systematic approach that separates strong analysis from weak attempts. Students who outline before drafting, choose distinct non overlapping categories, and provide 2-4 specific examples per category produce essays that demonstrate sophisticated analytical thinking. Start by browsing our topic collection, download outline templates to structure your planning, study annotated examples to see techniques in action, and master thesis formulas for strong foundations.

-19438.jpg)