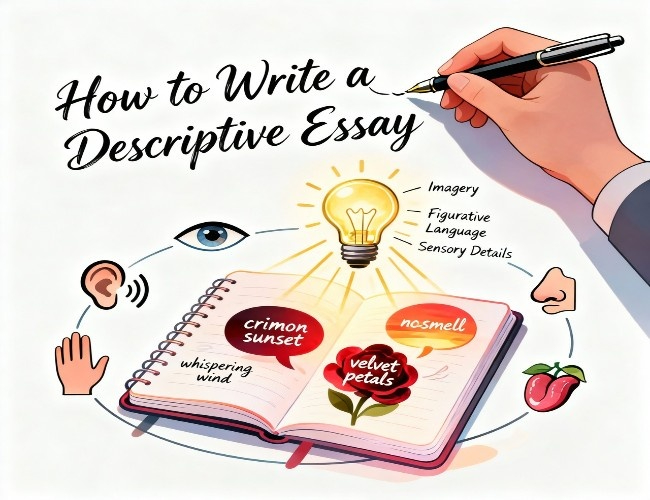

What Is a Descriptive Essay?

A descriptive essay paints vivid mental pictures using sensory details across all five senses. You're not just saying "the beach was beautiful"; you're showing turquoise waves rolling onto white sand, their rhythmic crash harmonizing with seagulls overhead, as salt spray stings your lips.

Descriptive Essay Characteristics

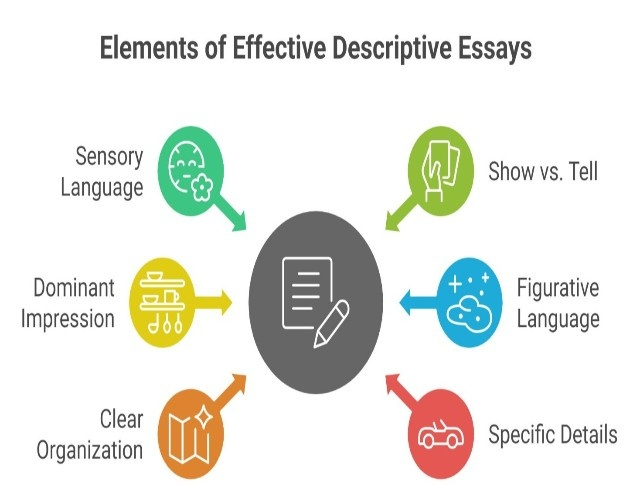

Six elements define effective descriptive essays:

1. Sensory Language: Engage all five senses, sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch, to create immersive experiences readers can feel.

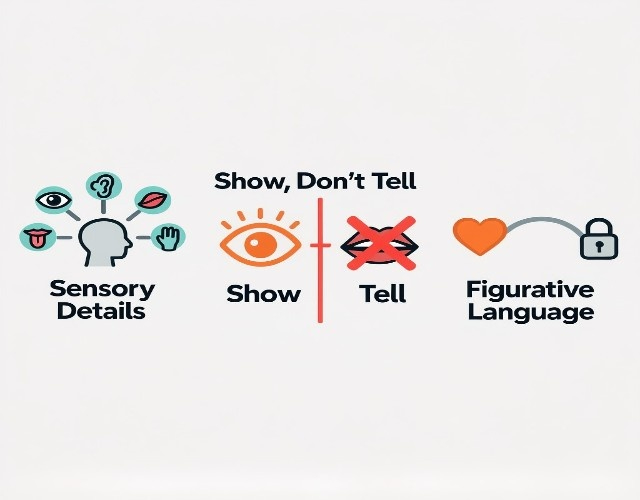

2. Show vs. Tell: Provide observable evidence rather than stating facts. Show "hands trembled as she shuffled note cards repeatedly" instead of telling "she was nervous."

3. Dominant Impression: Unify all details around one central feeling or mood. If describing grandmother's kitchen with "warmth and tradition" as your theme, every detail, from yeasty bread aroma to worn wooden spoons, supports that feeling.

4. Figurative Language: Use similes ("clouds drifted like cotton balls"), metaphors ("the city was a concrete jungle"), and personification ("wind whispered secrets") to enhance imagery.

5. Clear Organization: Structure descriptions spatially (left to right), sensorially (by sense), or chronologically (through time) so readers follow easily.

Start with a descriptive essay outline to save time and improve clarity in your writing.

6. Specific Details: Replace vague words with precise ones. Not "red car" but "cherry-red convertible gleaming under streetlights." Not "loud noise" but "thunderous roar shaking windows."

- Use transitions: Guide readers smoothly between ideas with spatial ("to the left"), temporal ("meanwhile"), or logical ("similarly") transitions.

See these principles demonstrated in annotated descriptive essay examples with highlighted techniques showing exactly how effective writers execute show-versus-tell throughout complete essays.

NO TIME TO WRITE IT ALL?

Let our writers handle the sensory details

- 100% human-written, zero AI

- Vivid description that transports readers

- Delivered on time, every time

- Written by degree-holding experts

Unlimited revisions. Real writers who know sensory language.

Order NowWhat You Can Describe in Descriptive Essays

1. People: Capture physical appearance, mannerisms, voice, and behavior. Show personality through observable details, weathered hands with ink-stained fingertips, a laugh that erupts like barking, followed by wheezing, perpetual coffee smell clinging to flannel shirts.

2. Places: Transport readers into settings through atmosphere, physical details, and spatial relationships. Describe your childhood bedroom, a bustling intersection, a mountain summit, layering visual details with sounds, smells, and atmospheric qualities.

3. Experiences: Capture moments through sensory immersion. Your first day at a new school, a memorable concert, learning to swim, emphasis falls on what you saw, heard, smelled, tasted, and touched during that experience.

4. Objects: Examine meaningful items in sensory detail. Your father's watch, an inherited quilt, and a worn baseball glove describe visual appearance, tactile qualities, sounds, and even smells, revealing significance through physical characteristics.

Need help choosing? Browse descriptive essay topics organized by type and difficulty to find your perfect subject.

How to Write a Descriptive Essay

Step 1: Choose Your Subject

Pick something you've personally experienced with strong sensory memories. The best topics have:

- Observable details you've witnessed firsthand.

- Rich sensory potential engaging 3+ senses.

- Personal connection creating an authentic description.

- Specific focus is narrow enough for detailed treatment.

- Appropriate scope matching your word limit

For Instance:

| Good: "My grandmother's Sunday kitchen". |

| Too broad: "My grandmother's entire house". |

| Good: "The moment I saw the ocean for the first time". |

| Too vague: "A beach I like". |

Step 2: Establish Dominant Impression

Decide the overall feeling your description should create: warmth and safety, vibrant chaos, peaceful isolation, or foreboding decay. This becomes your thesis and guides every detail you include.

Thesis examples:

- "The library represented a sanctuary, quiet and timeless, where worlds opened within pages."

- "My grandmother's kitchen embodied warmth and tradition, a place where memories formed over simmering pots."

Learn more about the descriptive essay thesis statement in our descriptive essay examples guide.

Step 3: Gather Sensory Details

List specific observations for each sense:

- Sight: Colors (crimson, azure, amber), lighting, movement, textures.

- Sound: Volume, quality, rhythm, source (hiss, clatter, murmur).

- Smell: Comparisons to familiar scents, intensity, pleasantness.

- Touch: Textures (rough, silky, sticky), temperature, weight.

- Taste: Sweet, sour, bitter, salty, umami combinations.

Our descriptive essay outline helps you plan vivid sensory details and keep your writing focused.

Step 4: Choose Organization Method

- Spatial: Move through physical space (left to right, top to bottom, outside to inside). Best for places and objects.

- Sensory: Dedicate paragraphs to different senses. Best for experiences engaging multiple senses simultaneously.

- Chronological: Follow time progression while maintaining descriptive focus. Best for events or experiences unfolding over time.

Step 5: Write Your Introduction

Many students struggle with how to start a descriptive essay, but the right opening can instantly capture a reader’s attention

- Hook with immediate sensory detail: "Thunder rolled across the valley, each boom reverberating in my chest like a bass drum."

- Provide brief context: "Every Saturday morning for twenty years, I've returned to this diner."

- State your dominant impression (thesis): "The library represented a sanctuary, quiet and timeless, where worlds opened within pages and reality paused outside oak doors."

Step 6: Develop Body Paragraphs

Each paragraph should:

- Begin with topic sentence: "The stove anchored the kitchen, a cast-iron beast perpetually radiating warmth."

- Layer 3-5 sensory details: Engage multiple senses with specific observations.

Show, don't tell: Instead of "it was cozy," show "afternoon sunlight slanted through lace curtains, illuminating dust particles dancing above worn oak floorboards."

- Maintain dominant impression: Every detail reinforces your central theme.

Step 7: Wrap Up Your Essay (Write Your Conclusion)

- Reinforce dominant impression without repeating: "The warmth radiating from that kitchen wasn't merely temperature, it was the heat of family, tradition, and love simmering across decades."

- Reflect on significance: "Years later, when I smell rising bread, I'm transported instantly to that kitchen, that time, that feeling of belonging."

- End with vivid final image: "Even now, I hear her humming while rolling dough, flour dusting her small hands like clouds of snow."

Remember! A strong descriptive essay conclusion should leave the reader with a lasting impression of the scene, person, or experience you’ve described.

Descriptive Writing Techniques

1. Master Show vs. Tell

The fundamental principle: provide observable evidence instead of stating facts.

| Telling: "The beach was beautiful." |

| Showing: "Turquoise waves rolled onto white sand, their rhythmic crash harmonizing with seagulls' cries. Sunlight glittered across water like scattered diamonds." |

| Telling: "He was angry." |

| Showing: "His jaw clenched tight. Knuckles whitened as he gripped the steering wheel. Words came out clipped and sharp, each syllable bitten off." |

| Telling: "The restaurant was busy." |

| Showing: "Silverware clinked against plates as servers weaved between crowded tables. Conversation hummed beneath jazz piano melodies. The kitchen door swung open every few seconds, releasing garlic and butter aromas." |

Practice this: For every statement, ask "What would someone SEE, HEAR, SMELL, TASTE, or TOUCH that shows this?"

2. Use Sensory Language

Sight, Be specific

|

Sound, Layer audio

|

Smell, compared to a familiar

|

Touch, Describe texture

|

Taste, Use categories

|

Note: Understanding the characteristics of descriptive writing, such as vivid imagery, sensory details, and precise language, can help you create more engaging and memorable essays.

3. Apply Figurative Language

Similes (using "like" or "as")

|

Metaphors (implicit comparisons)

|

Personification (human qualities to non-human things)

|

Use sparingly but powerfully, one strong metaphor combined with specific sensory details beats multiple weak comparisons.

DEADLINE APPROACHING?

Stop gambling with your grades. Our professionals deliver custom papers that professors actually want to read.

- Custom sensory descriptions

- Any topic, any deadline

- PhD writers available

- Full confidentiality guaranteed

No AI. Just real writers who craft vivid descriptions.

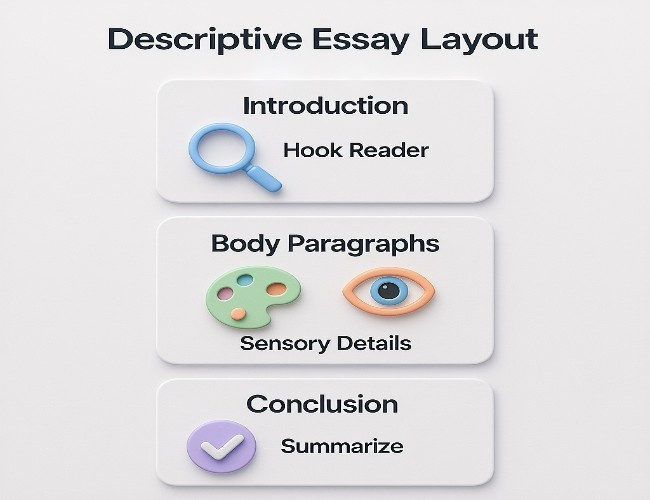

Order NowDescriptive Essay Layout

Introduction (10-15%)

Components

- Hook: Immediate sensory immersion.

- Context: Brief background (1-2 sentences).

- Thesis: Your dominant impression is clearly stated.

- Preview (optional): Organizational approach.

Body Paragraphs (70-80%)

- Organization options.

- Spatial (for places/objects).

- Sensory (for experiences).

- Chronological (for events)

Conclusion (10-15%)

Avoid: Simply restating what you already described

Check descriptive essay examples for more guidance on crafting engaging and detailed essays.

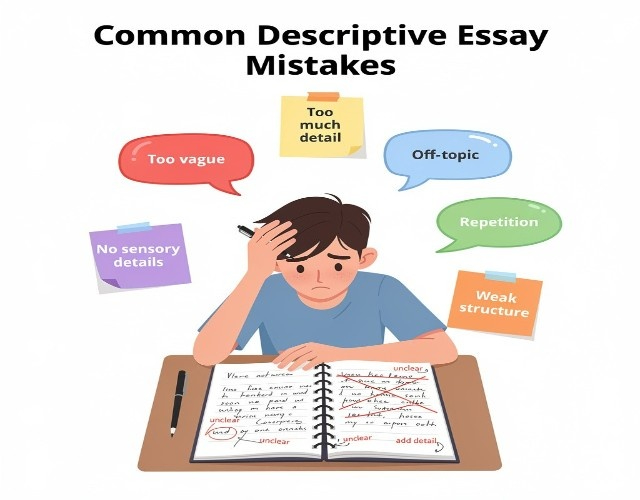

Common Descriptive Essay Mistakes to Avoid

Mistake #1: Too Much Telling

Problem: Stating facts instead of providing evidence.

Fix: Replace every "telling" statement with observable details.

- "The room was messy".

- "Clothes draped over chairs. Books stacked in leaning towers. Coffee cups left rings on every surface."

Mistake #2: Vague Language

Problem: Generic adjectives that don't create pictures.

Fix: Use specific, precise vocabulary.

- "The car was nice and red".

- "The cherry-red convertible gleamed under streetlights, chrome bumper reflecting passing headlights in rippling waves."

Mistake #3: Only Using Sight

Problem: Describing only visual details, ignoring other senses.

Fix: Engage 3-4 senses minimum per description.

Add: Sounds, smells, textures, tastes when relevant.

Mistake #4: No Dominant Impression

Problem: Random details without a unified feeling.

Fix: Establish a central mood in the thesis; select only supporting details.

Test: Does this detail reinforce my theme? If no, cut it.

Mistake #5: Plot Summary Creep

Problem: Telling what happened instead of describing what things felt like.

Fix: Focus on sensory immersion of moments, not event sequence.

- "Then we ate dinner. After that, we went home."

- "Garlic and rosemary filled the air as steam rose from pasta bowls, each bite rich with butter and herbs."

Mistake #6: Clichéd Comparisons

Problem: Overused similes and metaphors that add nothing.

Fix: Create original, unexpected comparisons.

- "White as snow," "quiet as a mouse," "strong as an ox".

- "Wrinkles deep as canyons," "silence thick as wool."

Descriptive Essay Quick Tips Summary

1. Before Writing:

| Before Writing | Yes / No |

|---|---|

| Choose a subject you’ve personally experienced | Yes / No |

| Establish a dominant impression (central feeling) | Yes / No |

| List sensory details for all five senses | Yes / No |

| Select an organizational method (spatial, sensory, or chronological) | Yes / No |

2. While Writing

| While Writing | Yes / No |

|---|---|

| Show through details rather than telling through statements | Yes / No |

| Use specific, precise vocabulary | Yes / No |

| Engage 3–4 senses in each description | Yes / No |

| Layer 3–5 sensory details per paragraph | Yes / No |

| Maintain the dominant impression throughout the essay | Yes / No |

3. After Writing

| After Writing | Yes / No |

|---|---|

| Highlight show vs. tell moments. Is more showing needed? | Yes / No |

| Count the senses engaged. Does it rely too heavily on visuals? | Yes / No |

| Check the dominant impression. Does every detail support the theme? | Yes / No |

| Replace vague words with specific alternatives | Yes / No |

| Add transitions for smooth, logical flow | Yes / No |

Writing a descriptive essay can be challenging, especially when deadlines are tight or the topic requires polished language. If you need expert assistance, a professional essay writing service can help turn your ideas into a well-structured, vivid essay that meets academic standards.

Free Descriptive Essay Downloadable Resources

Why Struggle When Experts Can Do It Better?

Thousands of students trust us to deliver essays that get the grades they deserve.

- Vivid sensory language

- Perfect show vs. tell execution

- Any deadline, any topic

- Written by academic specialists

100% original. 100% human. Satisfaction guaranteed.

Order NowBottom Line

Descriptive essays transport readers through sensory language. Master show vs. tell, engage multiple senses with specific details, maintain a dominant impression, and choose subjects you've personally experienced. With practice and the techniques covered here, you'll write descriptions that make readers feel they've experienced your observations firsthand.

-19521.jpg)

-19514.jpg)

-19525.jpg)

-19543.jpg)