Why Does Balancing Social and Academic Life Feel Impossible?

Balancing social and academic life feels impossible because college genuinely presents more demands than 24-hour days accommodate requiring prioritization and strategic sacrifice, academic pressure intensifies through harder material, higher stakes, and competitive environments where adequate performance requires 40-50 hours weekly, social opportunities multiply compared to high school with hundreds of potential activities and friendships requiring time investment, and the absence of external structure means you must create your own systems while everyone around you appears to manage everything effortlessly creating pressure and comparison.

Research reveals that 75 to 80% of college students report feeling they lack adequate time for both academics and social life, with 60 to 65% saying they sacrifice one area to maintain the other.

Studies on time allocation show college students average 42 to 48 hours weekly on academics, including classes, studying, and assignments, leaving 40 to 45 hours for sleep, meals, self-care, work, and socializing, barely enough for everything when calculated realistically rather than optimistically.

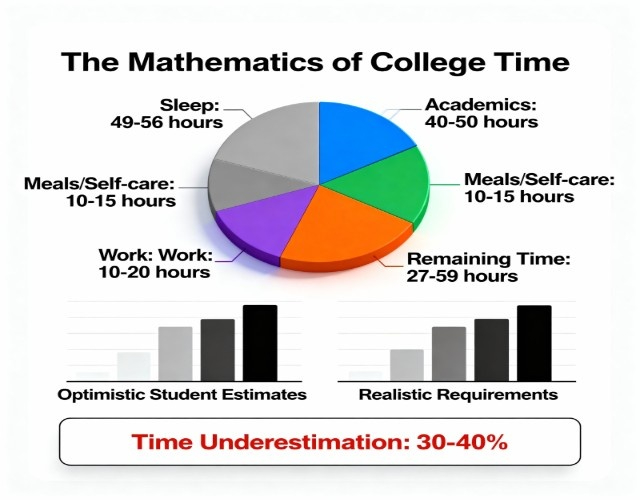

1. The Mathematics of Time Don't Add Up

A realistic breakdown reveals why balance feels impossible. You need 49-56 hours for sleep at 7-8 hours nightly. Classes and studying require 40-50 hours weekly for full-time students. Meals, hygiene, and basic self-care need 10-15 hours. Work takes 10-20 hours for many students. That totals 109-141 hours from the 168 hours available weekly.

The remaining time is 27-59 hours for social life, exercise, hobbies, commuting, unexpected events, and buffer time. Research shows students consistently underestimate time requirements by 30-40% when planning schedules. What seems like ample time disappears when accounting for transitions, interruptions, and inefficient work periods.

Part-time work dramatically affects balance. Students working 15-20 hours weekly report 40-50% less time for social activities compared to non-working peers. Those working 25+ hours experience severe time scarcity, averaging just 5-8 hours weekly for socializing.

Studies indicate that working students achieve similar GPAs to non-working peers only by sacrificing social engagement, sleep, or both to maintain academic performance.

Commuting compounds time pressure. Students with 30-60 minute commutes lose 5-10 hours weekly to transportation that residential students use for studying, socializing, or sleeping. Research shows commuter students participate in 50-60% fewer campus activities than residential students, primarily due to time and logistics rather than interest differences.

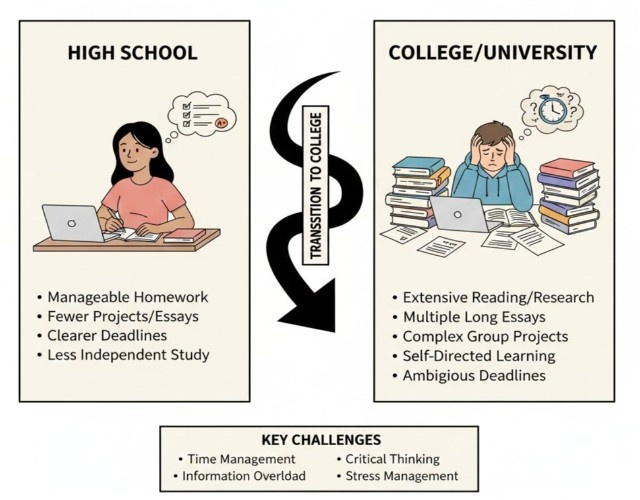

2. Academic Demands Increase Significantly

College coursework requires substantially more time than high school. The standard expectation is 2 to 3 hours of studying per credit hour, meaning 15 credits demands 30 to 45 weekly study hours plus 15 class hours for 45 to 60 total academic hours. This exceeds the typical 35 to 40-hour high school schedules. Research reveals that students in STEM majors average 55 to 65 hours weekly on academics, while humanities students average 45 to 55 hours. Both exceed the "full-time job" standard.

Course difficulty jumps dramatically. Material that previously felt manageable now requires multiple readings and additional resources to understand. Professors expect independent learning rather than explicit instruction for everything. Studies show that 65 to 70% of college students report feeling academically overwhelmed during their first year, with 50 to 60% saying coursework takes significantly longer than anticipated.

High stakes intensify pressure. Individual assignments worth 20 to 30% of grades create anxiety, unlike distributed high school grading. Failed exams or papers can drop grades by a full letter. Research indicates that grade-related stress affects 70 to 75% of college students, with 45 to 50% reporting stress severe enough to impair sleep, relationships, or physical health.

3. Social Opportunities Multiply, Creating FOMO

College offers vastly more social options than high school, hundreds of clubs, frequent parties, campus events, diverse friend groups, and a culture valuing social engagement as part of "the college experience." This abundance creates decision fatigue and fear of missing out. Research shows that 55 to 65% of students report FOMO interfering with academic focus, with social media amplifying awareness of events you're missing.

Social comparison through social media shows everyone else apparently attending parties, hanging out with friends, and having great experiences while you study alone. These curated highlights create false impressions that others balance everything perfectly.

Studies reveal that 70 to 75% of students believe their peers have better social lives, while 65 to 70% believe peers handle academics more easily, meaning most students feel they're failing at balance while actually experiencing normal struggles.

The first-year pressure to establish friend groups adds urgency to social engagement. Missing events early on feels like missing chances to form crucial relationships. Research indicates that 60 to 70% of first-year students feel pressure to attend social events even when academically overwhelmed, with 40 to 50% making choices they later regret, prioritizing socializing over studying or vice versa.

4. Absence of External Structure

High school provided structure through mandatory attendance, parental oversight, and limited scheduling autonomy. College eliminates these guardrails, requiring you to create your own systems.

The freedom feels overwhelming when you're simultaneously learning how to manage harder coursework, navigate social dynamics, and handle adult responsibilities. Research shows that students with high parental structure in high school struggle 40 to 50% more with self-directed time management during their first college year compared to peers who had more independence.

Nobody checks if you attend class, complete assignments on time, or maintain healthy habits. Consequences for poor choices take weeks or months to materialize, unlike high school's immediate feedback. Studies indicate that 50 to 60% of first-year students struggle with procrastination that they didn't experience in high school, due to reduced external accountability.

5. Individual Capacity Differences

Time management advice often ignores that people have genuinely different capacities for work and social demands. Some students thrive on 6 hours of sleep, while others need 9. Some process information quickly while others require more study time for the same mastery.

Extroverts recharge through socializing, while introverts need solitude. Research reveals that individual differences in processing speed, working memory, and emotional regulation create 30 to 50% variance in the time required for equivalent academic outcomes.

Comparing yourself to others creates unrealistic expectations. The person who appears to balance everything perfectly might have fewer work hours, easier courses, higher baseline abilities, or might be struggling privately despite appearances. Studies show that 65 to 70% of students who appear highly successful to peers report feeling like impostors, barely maintaining the illusion of balance.

What Does Realistic Balance Actually Look Like?

Realistic balance means strategic uneven prioritization where academics receive 60 to 70% of discretionary time during regular weeks with social life getting 20 to 30% rather than perfect 50 to 50 splits, recognizing that balance varies by semester with midterms and finals requiring temporary social sacrifice while lighter weeks allow increased socializing, accepting that some activities get dropped as maintaining everything simultaneously exceeds sustainable capacity, focusing on quality over quantity in both academics and relationships rather than attempting to attend every event or achieve perfection in every class, and understanding that "balance" means long-term equilibrium across months rather than daily equal distribution.

Research on successful balanced students shows they average 40 to 45 hours weekly on academics, 8 to 12 hours on social activities, and 10 to 15 hours on sleep and self-care, with flexibility to adjust these ratios temporarily during high and low-pressure periods while maintaining semester-wide balance, resulting in 70 to 75% reporting high satisfaction in both academic and social domains.

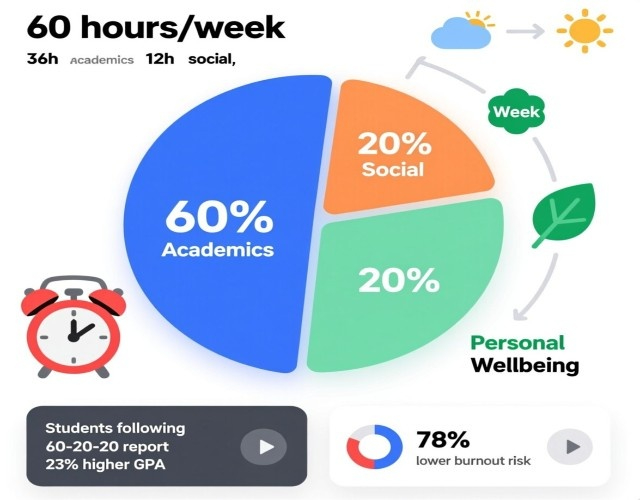

1. The 60-20-20 Framework

A sustainable weekly framework allocates approximately 60% of time beyond basic needs to academics, 20% to social connection, and 20% to personal wellbeing, including exercise, hobbies, and solitude. For a student with 60 hours weekly beyond sleep, meals, and basic care, this means 36 hours for academics, 12 hours for socializing, and 12 hours for self-care.

Research shows students following similar proportional frameworks maintain 0.3-0.5 point higher GPAs while reporting 40 to 50% better mental health compared to those attempting a perfect balance or sacrificing one area completely. These percentages shift temporarily during high-pressure periods. Midterms and finals might require 75 to 80% academic focus with reduced social time, while semester breaks allow inverted priorities.

The key is semester-wide balance rather than rigid weekly adherence. Studies indicate that students who adjust ratios seasonally rather than maintain inflexible structures achieve 25 to 35% better outcomes in both academics and relationships.

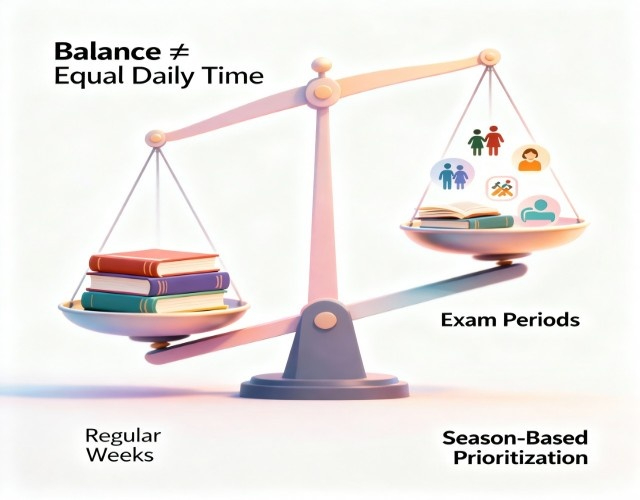

2. Season-Based Prioritization

Balance doesn't mean equal daily time distribution. Academic calendars create natural high and low-pressure periods. Regular weeks allow balanced engagement while exam periods require temporary academic focus. Research shows that students who intensively prioritize academics during 3-4 week high-stakes periods and then relax standards during lower-stakes weeks, achieve similar or better GPAs than those maintaining constant high effort while experiencing 30 to 40% less burnout.

Communicate seasonal shifts to friends, explaining that you'll be less available for two weeks during midterms but want to reconnect afterward. Most people understand temporary absence better than gradual disappearance. Studies reveal that friendships where partners communicate about availability fluctuations maintain 50 to 60% higher satisfaction than those where one person unpredictably ghosts during busy periods.

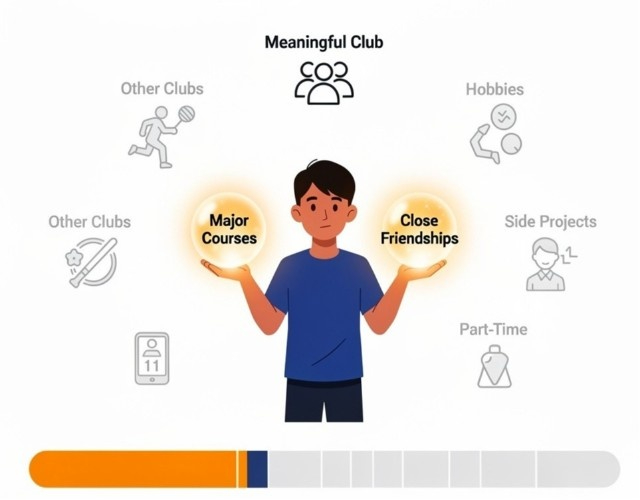

3. Selective Investment Strategy

You cannot excel at everything simultaneously. Choose 2 to 3 high-priority commitments, perhaps your major courses, one meaningful club, and close friendships, investing deeply in those while maintaining minimal engagement elsewhere.

Research shows students with focused priorities achieve 40 to 50% higher satisfaction than those spreading effort thinly across many commitments. Let some classes be B's if others require A's for your goals. Attend club leadership meetings but skip some social events. See close friends regularly but decline peripheral social invitations.

The "good enough" approach acknowledges limited capacity. Perfectionism across all domains creates unsustainable stress. Studies indicate that students who accept "good enough" in 60 to 70% of commitments while excelling in 30 to 40% report 45 to 55% lower stress levels and equal or better outcomes than perfectionists attempting excellence everywhere.

4. Quality Over Quantity in Both Domains

Academic balance means strategic studying rather than maximum hours. Three focused hours with breaks produce better learning than six distracted hours. Research shows that students studying 40 to 45 quality hours weekly outperform those studying 55 to 60 hours with poor focus by 15 to 25% on exams. Protect study time from interruptions, but work efficiently during those hours, creating space for other life aspects.

Social quality matters more than quantity. Two hours of meaningful one-on-one conversation with close friends provides more fulfillment than four hours of surface-level group socializing. Studies reveal that students with 3 to 5 close friends they see regularly report 40 to 50% higher social satisfaction than those with 10 to 15 casual acquaintances, despite the latter having larger social networks and more total social time.

6. Accepting Strategic Sacrifice

Balance requires dropping some opportunities even when they seem valuable. You cannot join five clubs, maintain a 4.0, work part-time, and have a robust social life simultaneously. Research shows that students involved in 1-2 activities deeply achieve 30 to 40% better outcomes than those involved in 4-5 superficially. Choose what matters most and accept that other valuable options must be declined.

This means experiencing FOMO regularly. Your friends will do things without you. You'll miss parties and events. Some opportunities disappear because timing didn't work. Studies indicate that students who accept FOMO as normal rather than emergency report 35 to 45% less social anxiety and make better priority decisions than those attempting to attend everything.

What Are the Most Effective Time Management Strategies?

The most effective time management strategies include time-blocking where specific hours are designated for studying, socializing, and personal time preventing any single demand from consuming everything, implementing the 2-hour rule where socializing happens after completing 2 to 3 hours of daily academic work creating guilt-free social time, front-loading work completing assignments several days before deadlines creating buffer time for unexpected social opportunities or academic challenges, using transition times for small tasks like reviewing flashcards between classes maximizing productivity in scattered 15 to 30 minute windows, and establishing protected time for both priorities through non-negotiable study blocks and scheduled social commitments rather than treating either as optional.

Research on high-performing balanced students shows they average 85 to 90% adherence to planned schedules with structured time management, complete assignments 3 to 4 days before deadlines creating flexibility, and maintain 8 to 12 hours weekly of scheduled social time treated as seriously as academic commitments, resulting in 0.3 to 0.4 point higher GPAs while reporting 40 to 50% more frequent social engagement compared to peers using reactive rather than proactive scheduling.

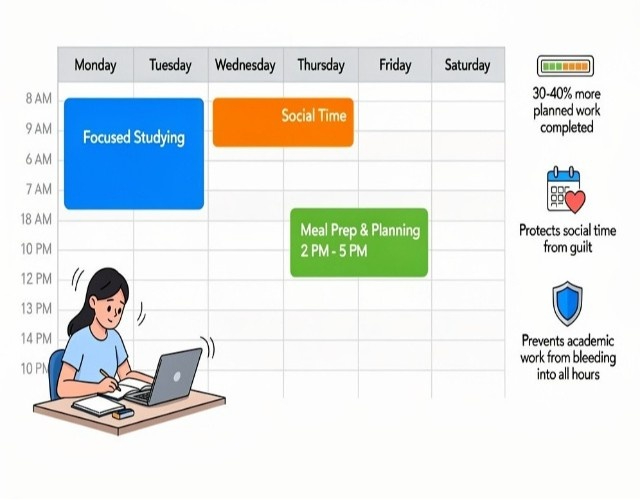

1. Time-Blocking for Structure and Protection

Time-blocking involves assigning specific hours to specific activities, creating a visual structure for your week. Block 9 AM to 12 PM Monday, Wednesday, Friday for focused studying. Block Tuesday and Thursday evenings for social time. Block Sunday afternoons for meal prep and planning. Research shows that students using time-blocking complete 30 to 40% more planned work compared to those using to-do lists without scheduled times. The visual structure prevents academic work from bleeding into all available hours while protecting social time from guilt.

Digital calendars work better than paper for time-blocking as they're always accessible and can send reminders. Color-code different activity types: red for classes, blue for studying, green for social, and yellow for self-care. Studies indicate that visual differentiation increases schedule adherence by 25 to 35% compared to monochrome planning.

Build in 10 to 15 minute buffers between blocks, accommodating transitions, bathroom breaks, and unexpected delays. Schedules without buffers collapse when anything runs over. Research shows that schedules with 15 to 20% buffer time maintain 60 to 70% accuracy compared to 30 to 40% for packed schedules with no flexibility.

2. The 2-Hour Daily Work Minimum

Implement a personal rule requiring 2 to 3 hours of productive academic work before engaging in extended social activities each day. This ensures consistent academic progress even on social days while making socializing feel earned and guilt-free. Research shows students following similar minimum work requirements maintain 0.2 to 0.3 points higher GPAs than those with completely flexible scheduling while reporting equal social satisfaction.

The specific hour threshold matters less than consistency. Some students need 3 hours daily, while others function well with 2 hours. Calculate your weekly academic hour needs, then divide by seven, establishing your daily minimum. Studies indicate that daily minimums work better than weekly targets, as consistent daily effort prevents procrastination and last-minute cramming.

Weekend mornings often provide an ideal time for minimum requirements. Working 9 AM to 12 PM Saturday and Sunday provides your daily minimums, leaving afternoons and evenings completely free for socializing without academic anxiety. Research reveals that students who work weekend mornings report 50-60% less guilt about weekend social activities compared to those who defer all weekend work to Sunday night.

3. Front-Loading Assignments

Complete assignments 3-4 days before deadlines rather than the day before. This creates buffer time for unexpected social opportunities, last-minute complications, or realizing work requires more time than estimated. Research shows that students submitting work with 2+ day buffers score 10-15% higher on average due to time for editing and reduced stress. The buffer also allows spontaneous socializing when friends suggest activities on what would have been frantic last-minute work nights.

Break large assignments into smaller tasks scheduled across multiple days. A 10-page paper becomes 2 pages daily for five days rather than 10 pages in one desperate session. Studies indicate that distributed practice improves both learning and grades by 20-30% compared to massed practice while reducing stress by 40-50%.

4. Strategic Procrastination on Low-Stakes Work

Not all assignments deserve equal effort. Identify low-stakes assignments worth 5 to 10% of grades where "good enough" suffices while perfect performance provides minimal grade benefit. Do these assignments competently but quickly, reserving perfectionist effort for high-stakes work. Research shows that students who strategically differentiate effort by assignment stakes achieve 0.2 to 0.3 point higher GPAs than those who treat everything equally by avoiding wasted effort on minimal-impact work.

When facing a genuinely overwhelming workload where even strategic effort allocation can't create adequate time for both academic success and essential social connection, an essay writing service can handle assignments in less critical courses during peak-demand weeks, preserving time for high-priority exams and projects while maintaining the social connections, protecting your mental health, and overall college experience.

5. Using Transition and Dead Time

Scattered 10 to 30 minute gaps between classes, during commutes, or while waiting for appointments add up to 8 to 12 hours weekly. Use these for quick study tasks like reviewing flashcards, reading one article, or organizing notes. Research shows that students maximizing transition times gain 6 to 10 additional productive hours weekly without sacrificing scheduled social or study blocks. This captured time often makes the difference between sustainable and unsustainable schedules.

Keep study materials accessible on your phone or in your bag, enabling quick, productive use of unexpected free time. Studies reveal that students with mobile study resources complete 25 to 35% more micro-study sessions compared to those requiring specific locations or physical materials for all studying.

6. Saying No Strategically

Balance requires declining invitations even when you want to attend. Say yes to 60-70% of social invitations, no to 30 to 40%. Prioritize events with close friends, special occasions, or activities you genuinely enjoy over generic social gatherings. Research shows that students who decline 30 to 40% of social invitations maintain stronger close friendships and higher GPAs compared to those attempting to attend everything, resulting in superficial engagement everywhere.

Offer alternatives when declining, showing continued interest. "I can't do dinner tonight, but I want to grab coffee tomorrow morning?" maintains connection while protecting necessary study time. Studies indicate that declined invitations with specific alternative suggestions maintain relationship satisfaction 60 to 70% as well as acceptances compared to 30 to 40% for simple declines without alternatives.

How Do You Prevent One Area from Consuming Everything?

Prevent academics or social life from consuming everything by establishing firm boundaries including designated no-study times like Friday evenings or Sunday afternoons creating protected social space, implementing hard stop times for studying like "no work after 10 PM" preventing endless all-nighters, scheduling social commitments in advance treating them as seriously as academic deadlines, using accountability systems where friends or study partners help maintain boundaries, recognizing when perfectionism drives unnecessary extra work yielding diminishing returns, and identifying when workload genuinely exceeds sustainable capacity requiring course load reduction or strategic support rather than continued sacrifice of wellbeing.

Research shows that students with clear boundaries around study and social time achieve 25 to 30% better balance satisfaction while maintaining equivalent GPAs to boundary less peers who work more total hours, with boundary students reporting 40 to 50% lower burnout rates and 30 to 40% better sleep quality.

1. Establishing Protected Social Time

Designate specific times as completely off-limits for academics, even when work remains incomplete. Friday evenings, Saturday afternoons, or Sunday mornings might be your protected social time where you attend events, see friends, or enjoy hobbies guilt-free, regardless of academic status.

Research shows that students with 6 to 10 hours weekly of protected social time maintain 30 to 40% stronger friendships while achieving equal GPAs to those working during that time due to improved focus during designated study hours.

Communicate protected times to yourself and others. Tell friends, "Friday evenings are my social time, I'll always be available then." Tell yourself, "I don't study Sunday mornings regardless of deadlines." Studies indicate that explicitly stated boundaries receive 60 to 70% better adherence than implicit flexible guidelines.

Resist the temptation to study during protected time, even when anxious about upcoming deadlines. The occasional protected time spent relaxing creates sustainable long-term patterns. Research reveals that students who violate protected time boundaries more than 10 to 15% of the time gradually eliminate those boundaries entirely within 4 to 6 weeks, returning to unbalanced patterns.

2. Implementing Hard Stop Times for Work

Set firm endpoints for daily studying, like "no academic work after 10 PM" or "I stop studying three hours before bed." Honor these stops even when work remains incomplete. Research shows that late-night studying produces 40 to 50% worse learning efficiency due to fatigue, while disrupting sleep that's crucial for memory consolidation. Students with hard stops average 0.15 to 0.25 higher GPAs than night-owl studiers despite fewer total study hours due to better sleep and higher daytime productivity.

Working until exhaustion creates unsustainable patterns. When you regularly work until unable to continue, you train yourself that work never truly ends, damaging both productivity and well-being. Studies indicate that hard stops increase next-day productivity by 30 to 40% through better rest and reduced burnout.

2. Treating Social Commitments Like Academic Deadlines

Schedule social activities in your calendar, treating them as seriously as classes or exams. When friends suggest plans, add them to your calendar immediately. Avoid canceling social commitments for academic work unless in truly emergency situations.

Research shows that students who cancel social plans for academic reasons more than 20 to 25% of the time gradually lose friendships as friends stop inviting them, with 60 to 70% reporting feeling socially isolated by their junior or senior year.

The reciprocal rule: if you'd feel comfortable canceling an academic commitment for social reasons (you wouldn't), don't cancel social commitments for academic reasons. Except for genuine emergencies like unexpected exams or project deadlines, honor both equally. Studies reveal that equal treatment of social and academic commitments creates 45 to 55% better balance outcomes. |

3. Using Accountability Partners

Partner with friends or study buddies who help enforce boundaries. Tell your roommate, "Don't let me study past 11 PM," or tell friends, "Make me come out Friday even if I say I'm too busy." External accountability increases boundary adherence by 40 to 50% compared to self-imposed limits. Research shows that students with accountability partners maintain balanced behaviors 60 to 70% longer than those relying solely on willpower.

Study groups provide academic accountability, preventing procrastination, while the scheduled social component of working together maintains relationships. Meeting twice weekly for 2-3 hours creates 4-6 hours of combined productive and social time. Studies indicate that students in consistent study groups complete 30 to 40% more assignments on time while reporting 25 to 35% more social satisfaction than solo studiers.

4. Recognizing Diminishing Returns

Perfectionism drives unnecessary extra work, yielding minimal grade improvements. Going from 90% to 95% on an assignment might require tripling your time investment for a marginal grade increase.

Research shows that effort has diminishing returns beyond 80 to 85% quality thresholds, with additional time producing 60 to 70% less grade improvement per hour invested. Learn to recognize "good enough" stopping points, freeing time for other priorities.

| The 80-20 rule applies to academic work: 80% of the grade benefit comes from 20% of effort, while the final 20% of the grade benefit requires 80% of effort. Studies reveal that students who focus their effort on high-impact activities rather than perfectionist polishing achieve similar GPAs in 30 to 40% fewer hours, creating substantial time for social life. |

5. Knowing When Workload Is Genuinely Unsustainable

Sometimes, struggling balance doesn't reflect poor time management but genuinely excessive demands. If you're consistently working 60+ hours weekly on academics with minimal social life and adequate sleep, the problem is workload, not your management.

Research shows that course loads exceeding 16 to 17 credits, particularly in difficult majors, create unsustainable demands for 70 to 80% of students regardless of time management quality.

When workload consistently prevents basic needs like adequate sleep, regular meals, or any social connection, make structural changes. Drop a class, reduce work hours, or seek support through a reliable essay writing service for lower-priority courses during temporarily overwhelming periods.

Studies indicate that students who adjust workload when unsustainable achieve 0.2 to 0.3 point higher GPAs and report 50 to 60% better mental health compared to those who continue pushing through impossible demands.

What If You've Already Lost Balance?

Recover lost balance by conducting honest assessment identifying which domain you've been neglecting and specific consequences you're experiencing, making one small change immediately rather than attempting complete overnight transformation such as scheduling one social event weekly or implementing one 2-hour study block daily, communicating with affected people explaining your situation and commitment to change whether that's friends you've been neglecting or professors about struggling coursework, addressing underlying issues like depression, anxiety, or perfectionism that may be driving imbalanced patterns beyond just time management, and giving yourself 3-4 weeks to reestablish sustainable patterns recognizing that recovery takes time and setbacks are normal.

Research on students recovering from severe imbalance shows that 70 to 75% successfully reestablish sustainable patterns within 4 to 6 weeks when implementing gradual changes with support, compared to just 20 to 30% success rates for those attempting sudden, dramatic overhauls.

Studies reveal that students who recover from imbalance report long-term better outcomes than peers who never struggled, developing stronger self-awareness and boundary-setting skills through the recovery process.

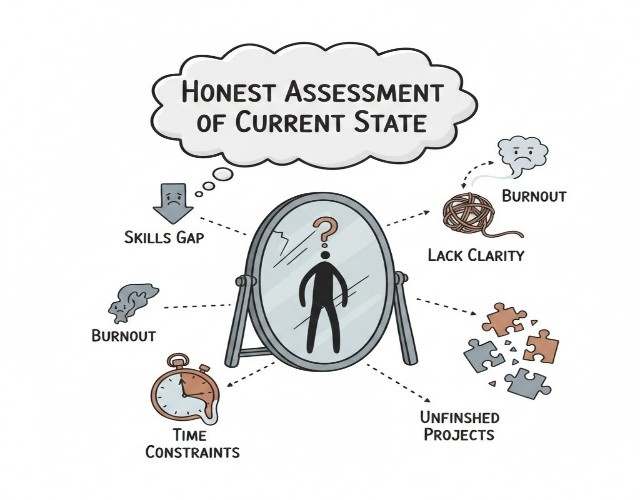

1. Honest Assessment of Current State

Start by tracking one typical week, documenting hours spent on classes, studying, socializing, sleeping, working, and other activities. Calculate actual time distribution rather than estimated or ideal patterns.

Research shows that students' perceptions of time use differ from reality by 30 to 50% with most underestimating study time while overestimating social time or vice versa. Accurate data reveals where the imbalance exists and how severe.

Assess consequences in neglected areas. If academics suffered, what's your current GPA, and how far below your goals? If social life vanished, how many close friends do you regularly see, and how does this compare to six months ago? Quantifying impact creates urgency for change. Studies indicate that students who specify measurable consequences show 40 to 50% higher motivation for behavior change compared to those with vague dissatisfaction.

2. Starting With One Small Change

Complete transformation overwhelms. Choose one specific small change you'll implement this week. If you've neglected social life, schedule one coffee date or attend one club meeting. If academics slip, implement one 2-hour morning study block.

Research shows that single-focused changes succeed 65 to 75% of the time, while multiple simultaneous changes succeed just 15 to 25% of the time due to willpower depletion.

Build momentum through small wins. Successfully maintaining one change for 2-3 weeks creates confidence and patterns enabling additional changes. Studies reveal that students who use gradual progressive change average 3-4 sustained new habits after three months, compared to 0-1 for those attempting sudden comprehensive overhauls.

3. Communicating and Rebuilding

Explain your situation to the affected people. Tell neglected friends, "I've been completely consumed by academics, and I miss you. Can we schedule regular hangouts?" or tell professors, "I've been overwhelmed and struggling, what support is available?" Research shows that 70 to 80% of people respond positively to honest vulnerability and explanation compared to confusion and hurt when you simply disappear, then reappear without context.

Rebuilding friendships requires consistent presence over weeks. Don't expect instant restoration of closeness after months of absence. Show up regularly, follow through on plans, and gradually trust. Studies indicate that damaged friendships require 4-6 weeks of consistent positive interaction before reaching previous closeness levels.

4. Addressing Underlying Issues

Sometimes imbalance stems from mental health conditions rather than just poor planning. Depression reduces motivation for social engagement, while anxiety drives perfectionist academic overwork. If an imbalance accompanies persistent low mood, excessive worry, panic symptoms, or difficulty functioning, seek professional evaluation.

Research shows that 45 to 55% of students with severe persistent imbalance have underlying treatable conditions contributing to the pattern.

Campus counseling provides assessment and treatment for conditions affecting balance. Cognitive behavioral therapy helps with anxiety-driven perfectionism, while treatment for depression restores energy and motivation for neglected life areas. Studies reveal that students addressing underlying mental health conditions alongside implementing practical strategies achieve 60 to 70% better balance outcomes than those using time management alone.

5. Giving Recovery Adequate Time

Reestablishing balance takes 4-6 weeks minimum. Don't expect perfect equilibrium after one good week. Patterns built over months require a similar timeframe to change.

Research shows that behavior change follows J-curves with initial difficulty before improvement, typically requiring 21 to 28 days for new habits to feel automatic. Students who abandon changes after 1 to 2 weeks miss the approaching success point.

Expect setbacks and imperfect weeks. One week slipping back to old patterns doesn't erase progress. Studies indicate that successful long-term behavior change includes 2-4 temporary relapses on average before sustained maintenance. What matters is returning to new patterns after setbacks rather than viewing single failures as complete defeats.

Key Takeaways

Successfully balancing social life and academic success requires strategic prioritization, realistic expectations, and recognition that perfect equilibrium is impossible:

- Balance means uneven prioritization with 60 to 70% of time focused on academics and 20 to 30% on social connection, rather than 50 to 50 splits, with flexibility to adjust during high and low-pressure periods.

- Students maintaining 8 to 12 hours weekly of social engagement achieve 0.2 to 0.3 point higher GPAs than socially isolated peers while reporting 40 to 50% better mental health.

- Most effective strategies include time-blocking, 2 hour daily work minimums, front-loading assignments 3 to 4 days before deadlines, and establishing protected time for both priorities.

- Prevent one area from consuming everything through firm boundaries like designated no-study times, hard stop times for work, treating social commitments seriously as academic deadlines, and recognizing diminishing returns of perfectionism.

- Severe persistent imbalance despite genuine effort signals underlying issues like depression, anxiety, unsustainable workload, or poor major fit requiring professional support or structural changes

The cultural promise of "having it all" in college sets unrealistic expectations, creating unnecessary guilt and stress. The mathematics simply don't support perfect balance, as college genuinely presents more demands than hours available, requiring conscious prioritization and strategic sacrifice. Students who accept this reality and make intentional choices about what matters most achieve better outcomes than those attempting to excel equally everywhere.

What matters most is identifying your priorities and allocating time accordingly, rather than defaulting to reactive patterns where whoever yells loudest gets your attention.

Academic success without social connection creates miserable, isolated experiences, while social focus without academic progress jeopardizes future opportunities. The sweet spot involves consistent academic investment, creating sustainable performance while protecting essential social time, maintaining mental health, and meaningful relationships, enriching your college experience beyond just grades.

When workload genuinely exceeds sustainable capacity despite strategic time management making balance temporarily impossible during peak-demand periods, seeking appropriate support maintains both your academic standing and essential social connections rather than forcing a complete sacrifice of one domain.

The goal isn't perfect equal distribution but sustainable long-term patterns where both academics and relationships receive adequate attention across your college years, creating a foundation for a fulfilling, successful life beyond graduation.