Detailed Analytical Essay Examples with Expert Analysis

Example 1: The Hidden Algorithm

The Hidden Algorithm: How Social Media Amplifies Teen Anxiety

When Instagram influencer Essena O'Neill quit social media in 2015, she revealed that her "perfect" photos required hundreds of takes and caused severe anxiety. Her confession highlighted what researchers now confirm: social media platforms don't just reflect teen mental health issues they actively amplify them through algorithmic design that rewards comparison and punishes authenticity.

While critics argue that social media simply makes existing teen anxiety more visible, the evidence suggests something more troubling. The specific design features of these platforms infinite scroll, like counts, and algorithmically curated feeds create psychological pressures that didn't exist before smartphones. Social media doesn't just document teen mental health decline; it accelerates it through features deliberately engineered to maximize engagement at the cost of well-being.

The infinite scroll feature creates a compulsion loop that makes it neurologically difficult for teens to stop using these platforms. Unlike magazines or television shows with natural endpoints, social media feeds refresh endlessly, each swipe triggering dopamine release that reinforces continued use. A 2019 study in the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology found that limiting social media to 30 minutes per day significantly reduced depression and loneliness in college students. The reduction wasn't from avoiding negative content it was from breaking the scroll pattern itself. This suggests the delivery mechanism, not just the content, damages mental health. When teens report feeling "trapped" on social media despite wanting to stop, they're describing the neurological reality of variable reward schedules that gambling addictions also exploit.

The visibility of "likes" and follower counts transforms social validation into quantifiable metrics, creating unprecedented anxiety about social standing. Previous generations experienced social comparison, but it remained subjective and limited to known peers. Today's teens watch their social worth calculated in real time through public metrics visible to everyone. Research from the University of Pennsylvania found that reducing social media use to 10 minutes per platform per day led to significant decreases in loneliness and depression. Participants reported that removing constant comparison reduced their anxiety about how their lives measured against others. The like counter doesn't just show approval it creates a measurable hierarchy where every post becomes a performance evaluated by an audience. When Instagram briefly tested hiding like counts, teens reported feeling "less judged," suggesting the metric itself, rather than the content, generates stress.

Algorithmic curation prioritizes emotionally provocative content, ensuring teens encounter disproportionate amounts of material that triggers negative comparison. Social media feeds don't show random posts they show what algorithms predict will maximize engagement, which research confirms means content that provokes strong emotion. A Facebook internal study leaked in 2021 revealed that their algorithm amplified divisive content because it generated more interaction. For teens, this means their feeds overrepresent peers' highlight reels while hiding mundane reality, creating distorted perception that everyone else lives better. The algorithm isn't neutral it's a magnifying glass held over whatever makes users feel inadequate, because inadequacy keeps them scrolling.

Social media's impact on teen mental health goes beyond making problems visible it creates new psychological pressures through specific design choices. The infinite scroll exploits neurological reward systems, public metrics quantify social worth in damaging ways, and algorithms curate feeds that maximize comparison. Critics who dismiss these concerns as "kids these days" complaints miss that these platforms represent genuinely new psychological territory. Previous generations didn't carry devices engineered by teams of behavioral psychologists to be maximally addictive. Until platforms prioritize teen well-being over engagement metrics, parents and teens must recognize that social media isn't a neutral tool it's a system designed to exploit vulnerabilities that adolescents are especially ill-equipped to resist.

What Makes This Analytical Paper Example Work

|

Stop Stressing. Start Submitting. Our professional writers craft essays that impress professors and earn top marks. Trusted by 50,000+ students worldwide

Example 2: Carbon Pricing

Carbon Pricing: When Market Solutions Meet Political Reality

British Columbia implemented North America's first comprehensive carbon tax in 2008. Economists predicted it would reduce emissions while maintaining economic growth. Politicians feared it would destroy jobs and spark voter backlash. Fifteen years later, the results reveal something both groups missed: carbon pricing works technically but fails politically, making it an effective policy tool that democracies struggle to sustain.

The evidence shows carbon pricing achieves its intended environmental goal, reducing emissions but creates political vulnerabilities that threaten its long-term viability. This isn't a failure of economics or policy design; it's the collision between policies that work gradually and political systems that demand immediate, visible results.

British Columbia's carbon tax reduced emissions while the economy grew, proving the policy works as designed. The tax started at $10 per ton of CO2 in 2008, rising by $5 annually to reach $50 by 2021. Research published in Environmental and Resource Economics found that BC's emissions dropped 5-15% compared to what they would have been without the tax, while economic growth matched the rest of Canada. The policy generated revenue returned to citizens through tax cuts, making it revenue-neutral as promised. This contradicted predictions that carbon pricing would cripple economic competitiveness. Industries adapted through efficiency improvements rather than fleeing to jurisdictions without carbon taxes. The policy achieved exactly what economic theory predicted: pricing carbon made it economically rational to reduce emissions, and businesses responded to that incentive.

However, the tax's political sustainability proved fragile despite its policy success. In 2013, the government froze the tax at $30 per ton, abandoning the planned increases, after opposition parties made it a campaign issue. Voters in carbon-intensive regions felt disproportionately burdened, even though overall provincial emissions fell. The problem wasn't that the policy failed it was that climate benefits appeared slowly and diffusely while costs showed up immediately and specifically in gas prices. Research from the Canadian Institute for Climate Choices found that public support for carbon pricing correlates inversely with visibility: people support the concept but oppose seeing the cost at the gas pump. This visibility problem explains why carbon pricing faces constant political threats even when working exactly as intended.

Australia's experience confirms that technical success doesn't guarantee political survival. The country implemented a carbon price in 2012 that successfully reduced emissions by 17 million tons in its first year, according to the government's own data. Industries covered by the price cut their emissions as economic theory predicted. Yet in 2014, a new government repealed the policy, making Australia the only country to ever eliminate an established carbon price. Emissions promptly increased. The repeal happened despite the policy working precisely as designed because opponents successfully framed it as a "tax" that hurt families, even though revenue recycling offset costs for most households. The lesson: policies that impose diffuse future benefits while creating concentrated immediate costs face democratic vulnerabilities regardless of effectiveness.

Carbon pricing represents a paradox of democratic policymaking: what works technically may not survive politically. BC and Australia proved the policy reduces emissions while maintaining economic growth, validating economic theory. But both cases show that gradual, diffuse benefits struggle against concentrated, immediate costs in political systems that demand visible, rapid results. This doesn't mean abandoning carbon pricing it means recognizing that effective policy design requires political sustainability, not just technical effectiveness. Future climate policies must either engineer political coalitions through direct beneficiaries or accept that technically optimal solutions may not be democratically durable.

What Makes This Analytical Paper Example Work

|

Example 3: Evaluating "Ban TikTok"

Evaluating "Ban TikTok": When National Security Arguments Hide Protectionism

In a 2023 Wall Street Journal opinion piece, Senator Josh Hawley argues that national security concerns justify banning TikTok in the United States. While Hawley frames his argument around data privacy and Chinese surveillance, his evidence selection and omissions suggest the piece serves protectionist goals more than security concerns, using national security as politically palatable cover for economic nationalism.

Hawley's central claim that TikTok enables Chinese government surveillance relies on theoretical possibility rather than demonstrated occurrence. He writes, "TikTok's parent company ByteDance is subject to Chinese law requiring cooperation with intelligence services, meaning American user data could be accessed by Beijing." The phrase "could be accessed" does the argumentative work here it's hypothetically true but provides no evidence of actual access. Hawley cites no instances of Chinese government obtaining TikTok user data, no leaked documents showing surveillance, no whistleblowers reporting data transfers. The argument constructs a threat from possibility rather than evidence, which is rhetorically effective but logically weak. By contrast, documented cases of American tech companies providing user data to U.S. intelligence agencies receive no mention, suggesting Hawley's concern is less about surveillance generally and more about Chinese surveillance specifically.

The piece strategically omits that TikTok offered to store all U.S. user data on American servers operated by Oracle, addressing the stated concern while Hawley continued demanding a ban. This proposed "Project Texas" would have placed U.S. data under American control with oversight measures preventing Chinese access. Hawley dismisses this solution in a single sentence ("mere assurances aren't sufficient") without explaining why hosting data domestically wouldn't solve the surveillance problem he identifies. This omission matters because it reveals that data location doesn't actually resolve his objections, suggesting the article's stated rationale (data security) differs from its actual motivation. If preventing Chinese access to data were the genuine goal, American data storage would accomplish that. The quick dismissal implies the goal is eliminating the Chinese company itself, not securing American data.

Hawley selectively highlights TikTok's recommendation algorithm spreading "content Beijing wants Americans to see" while ignoring that American platforms like Facebook and Twitter use similar algorithms prioritizing engagement over truth. His article expresses alarm that TikTok might influence American users through algorithmic curation, stating "the algorithm can prioritize content that serves Chinese interests." Yet Meta's Facebook algorithm demonstrably amplified misinformation during the 2016 and 2020 elections, and Twitter's algorithm promoted conspiracy theories that led to real-world violence. Hawley's piece doesn't call for banning these platforms despite their proven track record of harmful algorithmic curation. The inconsistency suggests his concern isn't algorithmic manipulation generally but specifically Chinese-controlled algorithms, which positions the piece as protectionism (keeping out foreign competition) rather than security policy (preventing all algorithmic harm).

Senator Hawley's article deploys national security language to advance what amounts to economic protectionism. By emphasizing theoretical rather than demonstrated risks, omitting proposed solutions that would address stated concerns, and applying standards inconsistently across American and Chinese platforms, the piece reveals motivations beyond those it explicitly claims. This doesn't necessarily mean Hawley's conclusion is wrong reasonable people can support banning TikTok but his argumentative strategy undermines his credibility by misrepresenting protectionist goals as security imperatives.

What Makes This Article Analysis Essay Example Work

|

Example 4: Martin Luther King Jr.'s 'Letter with Annotations

Establishing Ethos in Martin Luther King Jr.'s 'Letter from Birmingham Jail'

[ANNOTATION: Hook establishes rhetorical situation and stakes]

When Martin Luther King Jr. penned his "Letter from Birmingham Jail" in April 1963, he faced a credibility problem: eight white clergymen had publicly called his civil rights demonstrations "unwise and untimely," questioning his judgment and leadership. King's response had to establish his authority to speak on racial justice while maintaining the moral high ground necessary for his civil rights message.

[ANNOTATION: Context explains the rhetorical challenge]

The letter responds to "A Call for Unity," a statement by Alabama clergymen arguing that racial issues should be pursued through courts rather than protests. King wrote from his jail cell, addressing fellow religious leaders who should have been natural allies but instead criticized his methods.

[ANNOTATION: Thesis makes a specific claim about rhetorical strategy and its effectiveness]

Through strategic use of ethos, the rhetorical appeal establishing speaker credibility, King transforms his vulnerability as a jailed protester into moral authority, positioning himself as more faithful to Christian principles than the clergymen who criticize him. He accomplishes this through three interconnected strategies: establishing shared identity as "fellow clergymen," demonstrating superior religious and philosophical knowledge, and showing that his actions align with the highest moral principles these clergymen claim to value.

[ANNOTATION: First body paragraph examines opening strategy]

King's opening immediately establishes common ground with his audience, creating a foundation for credibility through shared professional identity.

[ANNOTATION: Evidence showing deliberate framing]

King begins by addressing "My Dear Fellow Clergymen," a salutation he repeats throughout the letter.

[ANNOTATION: Analysis explains the rhetorical effect of this choice]

By calling his critics "fellow clergymen" rather than opponents or critics, King frames the disagreement as an internal professional debate among colleagues rather than a conflict between opposing sides. The word "fellow" emphasizes equality and shared calling, refusing to cede moral high ground despite being the one sitting in jail. This opening prevents readers from dismissing him as an outside agitator, the very charge the clergymen leveled, and instead positions him as an insider with equal claim to religious authority.

[ANNOTATION: Second evidence showing pattern]

He continues this strategy throughout:

"I am here, along with several members of my staff, because I have organizational ties here," and "I have the honor of serving as president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference."

[ANNOTATION: Analysis of organizational credentials]

King establishes institutional credibility by referencing his role leading a Christian organization, not a secular protest group. The word "honor" attached to "serving" reminds readers that his position represents recognition by other Christian leaders, not self-appointment. By mentioning "organizational ties," he refutes the "outside agitator" claim while simultaneously showing he leads a structured movement, not a chaotic mob. These credentials matter because they demonstrate other Christians including clergy trust his judgment and leadership.

[ANNOTATION: Second body paragraph shifts to intellectual authority]

Beyond professional credentials, King demonstrates a superior command of philosophical and religious tradition, establishing an intellectual ethos that surpasses his critics.

[ANNOTATION: Evidence showing range of references]

King cites Socrates, St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, Martin Buber, and Paul Tillich within a few paragraphs, weaving their ideas into his argument about just versus unjust laws.

[ANNOTATION: Analysis explaining the strategic purpose of scholarly references]

This intellectual breadth serves multiple rhetorical purposes. First, it demonstrates King's education and sophisticated thinking; he's not a simple protester but a learned scholar. Second, it shows his positions derive from established philosophical tradition, not improvised emotion. Third, it subtly shames his critics: King, sitting in jail, displays deeper engagement with moral philosophy than the comfortable clergymen who criticize him. The range itself matters he moves from ancient Athens (Socrates) through medieval Christianity (Augustine, Aquinas) to modern existentialism (Buber, Tillich), showing comprehensive rather than selective knowledge.

[ANNOTATION: Evidence showing biblical authority]

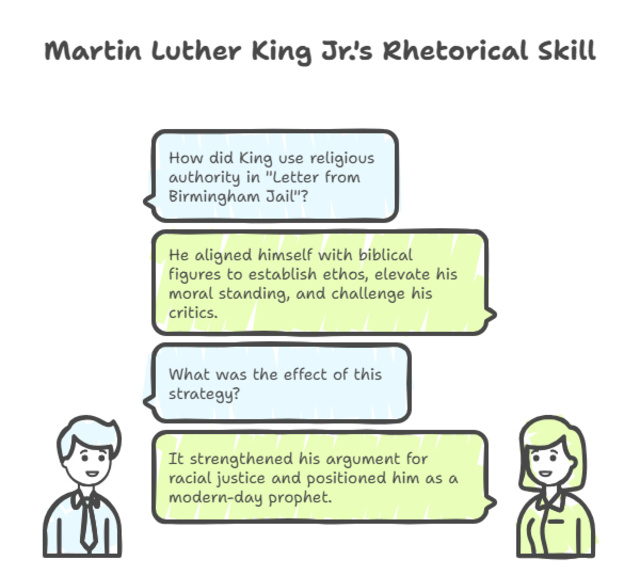

King references biblical figures extensively: "Just as the prophets of the eighth century B.C. left their villages and carried their 'thus saith the Lord' far beyond the boundaries of their home towns," and "I am in Birmingham because injustice is here. Just as the Apostle Paul left his village of Tarsus."

[ANNOTATION: Analysis of religious authority establishment]

By comparing himself to Old Testament prophets and Paul the Apostle, King claims the highest possible religious authority. These aren't controversial figures; they're central to Christian tradition that the clergymen must respect. The comparison argues: if prophets and Paul traveled beyond their homes to confront injustice, how can you criticize me for doing likewise? This moves King from questioned activist to prophet-in-the-tradition-of-Paul, dramatically elevating his moral authority while implicitly lowering his critics to the position of those who questioned biblical prophets.

[ANNOTATION: Third body paragraph examines moral authority through action]

Most powerfully, King establishes ethos by demonstrating his willingness to suffer for his principles, an authority his critics cannot match.

[ANNOTATION: Evidence highlighting physical sacrifice]

King writes from jail, a fact he emphasizes: "I am in Birmingham because injustice is here," and later, "I submit that an individual who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust, and who willingly accepts the penalty of imprisonment in order to arouse the conscience of the community over its injustice, is in reality expressing the highest respect for law."

[ANNOTATION: Analysis of embodied credibility]

His imprisonment becomes a rhetorical asset rather than a liability. By accepting jail time for his convictions, King demonstrates he practices what he preaches, unlike critics who advocate patience from positions of comfort.

The phrase "willingly accepts the penalty" is crucial: he's not dodging consequences but embracing them, showing his commitment exceeds what mere words require. This creates a powerful ethos: anyone can criticize safely; King risks his freedom.

[ANNOTATION: Comparison to critics establishing moral superiority]

The implicit comparison devastates his critics:

They write from comfort, safety, and freedom. He writes from jail. They advise patience. He suffers immediate consequences. They preserve order. He sacrifices for justice.

[ANNOTATION: Evidence showing this contrast made explicit]

King makes this comparison directly:

"I guess it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, 'Wait.'" The word "easy" contrasts comfort with suffering, making the clergymen's position seem cowardly by comparison.

[ANNOTATION: Conclusion synthesizes the three strategies]

King's masterful establishment of ethos transforms his vulnerable position into commanding moral authority. By claiming shared clerical identity, he prevents dismissal as an outside agitator. By demonstrating superior philosophical and biblical knowledge, he establishes intellectual authority exceeding his critics. By suffering for his principles, he creates embodied credibility that they cannot match.

[ANNOTATION: Addresses the effectiveness of combined strategies]

These three strategies work together powerfully. Shared identity provides a foundation, intellectual authority adds respect, and willing suffering creates moral credibility that overwhelms opposition. His critics cannot dismiss him as an uneducated troublemaker, cannot out-quote him on moral philosophy, and cannot claim greater Christian commitment when he sits in jail for his beliefs while they write from safety.

[ANNOTATION: Broader significance about rhetoric and social change]

King's letter demonstrates that effective rhetoric requires establishing multiple forms of credibility simultaneously. Logical arguments fail without ethos, establishing why audiences should trust the speaker. King doesn't just argue for civil rights; he proves he's qualified to lead that argument through professional credentials, intellectual sophistication, and moral courage exceeding his critics.

[ANNOTATION: Strong final thought connecting to historical impact]

The letter's enduring power stems from this credibility. King doesn't merely defend his Birmingham campaign; he establishes himself as a moral authority on racial justice, a position his critics can never reclaim once he's defined the terms.

Your Essay. Done Right. Delivered on Time. Tell us what you need — our experts handle the research, writing, and formatting. No AI shortcuts. Just expert-level quality.

Short Analytical Essay Example

Example 5: The Comfort of Ignorance

The Comfort of Ignorance: Plato's Cave and Modern Media Consumption

Plato's Allegory of the Cave describes prisoners chained since childhood to face a wall, watching shadows cast by a fire behind them. They believe these shadows are reality. When one prisoner escapes and sees the actual world, he returns to share this knowledge but finds his fellow prisoners prefer the shadows, attacking him for challenging their comfortable illusions. This ancient allegory perfectly captures modern media consumption: we voluntarily chain ourselves to algorithmically curated shadows, preferring comfortable illusions to challenging truths.

The cave prisoners couldn't turn their heads to see the fire creating the shadows physical chains prevented them. Modern media consumers face no such constraint. We can seek diverse sources, read opposing viewpoints, or investigate claims before sharing them. Yet algorithmic curation creates invisible chains more effective than Plato's literal ones. Netflix suggests shows based on viewing history. YouTube recommends videos similar to those previously watched. Facebook's News Feed prioritizes content that matches demonstrated preferences. Each click trains the algorithm to show more of the same, creating an echo chamber as confining as Plato's cave but disguised as choice. The prisoners couldn't escape their perspective; we refuse to escape ours, preferring the comfort of confirmation to the discomfort of challenge.

When confronted with information contradicting established beliefs, modern media consumers react like Plato's prisoners confronting the escaped prisoner with hostility rather than curiosity. Research on "backfire effect" shows that people presented with evidence contradicting firmly held beliefs don't change their minds; they double down on existing positions. Social media amplifies this response. Comments sections on political posts demonstrate Plato's insight: people reject information challenging their worldview not through reasoned disagreement but through attacks on the messenger. The escaped prisoner brought enlightenment and received hostility; modern fact-checkers bring evidence and receive accusations of bias. In both cases, the threat isn't to incorrect information but to the psychological comfort of certainty.

Yet Plato's allegory offers hope through its ending. The escaped prisoner persists despite hostility because he's experienced something undeniably real: the sun, genuine knowledge that shadows can't refute. For modern consumers, this means actively seeking disconfirming evidence and direct experience. Reading primary sources rather than summaries. Consuming media from multiple political perspectives. Talking with actual humans holding different views rather than reading about them. These actions break algorithmic chains not through massive effort but through small, consistent choices to see beyond shadows.

Plato understood that humans naturally prefer comfortable illusions to challenging truths, but he also believed education could overcome this preference. Twenty-four centuries later, technology has made both the illusions more comfortable and the truth more accessible. Whether we remain prisoners or choose escape depends on recognizing that the chains are real even when we can't see them, and that algorithms, like Plato's fire, cast shadows we mistake for reality.

Need a detailed structure breakdown? Our Analytical Essay Outline provides percentage guides, blank templates, paragraph structure explanations, and format variations for different essay lengths.

Example 6-8: Analytical Writing Samples (Quick Excerpts)

Due to space constraints, here are analytical essay body paragraph example excerpts from three more successful essays:

Example #6: Visual Storytelling in Parasite

Topic: Visual Storytelling in Parasite

Thesis: Bong Joon-ho uses vertical framing and spatial composition to literalize class hierarchy, making physical elevation synonymous with social superiority throughout Parasite.

Body Paragraph Excerpt:

The film's obsession with stairs manifests in nearly every scene transition. The Kim family's semi-basement apartment requires descending several steps from street level; they quite literally exist below society. When they travel to the Parks' home, the camera tracks their ascent up multiple staircases, each climb representing the social elevation they haven't earned. Bong positions the camera at low angles when shooting the Parks' home, emphasizing its towering presence, while the Kims' apartment is shot from eye-level or above, creating a claustrophobic, sunken feeling.

The most striking spatial metaphor occurs during the rainstorm: water floods downward through the city, devastating those at lower elevations while the Parks remain dry in their hilltop home. The Kims wade through sewage-filled streets, eventually sleeping in a gymnasium with hundreds of other displaced poor, horizontal sprawl replacing their usual vertical containment. This temporary elimination of hierarchy (everyone on the same level) proves short-lived; the next morning, they return to their flooded apartment, even lower than before.

What Makes This Analytical Essay Sample Work

|

Example #7: The Declaration of Sentiments (1848)

Topic: The Declaration of Sentiments (1848)

Thesis: Elizabeth Cady Stanton's deliberate mimicry of the Declaration of Independence's structure exposes American hypocrisy by using the founding document's own logic to indict gender inequality.

Body Paragraph Excerpt:

Stanton's opening, "We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal, makes her rhetorical strategy immediately clear. By adding "and women" to Jefferson's famous line, she performs textual subversion: the original phrasing supposedly meant all humans, yet required her amendment, proving it never did. This insertion functions as both a correction and an accusation.

The parallel structure continues with a list of grievances mimicking Jefferson's complaints against King George III: "He has never permitted her to exercise her inalienable right to the elective franchise" echoes "He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly." The pronoun shift matters, Jefferson's "He" meant the King; Stanton's "He" means all men, making every American man complicit in tyranny the Revolution supposedly ended. This rhetorical move proves devastating: if denying votes justified revolution against Britain, how do American men justify denying them to women? Stanton traps her opposition in their own founding logic.

What Makes This Analytical Essay Sample Work

|

Example #8: Nike's "Dream Crazy" Campaign

Topic: Nike's "Dream Crazy" Campaign

Thesis: Nike's Colin Kaepernick advertisement weaponizes controversy itself as a branding strategy, calculating that alienating some consumers will intensify loyalty among its core demographic.

Body Paragraph Excerpt:

The ad's copy, "Believe in something. Even if it means sacrificing everything," overlaid on Kaepernick's face, crystallizes Nike's risk-taking brand identity. The phrase operates on multiple levels: it references Kaepernick's career sacrifice for protesting police brutality, aligns Nike with social justice movements, and positions the brand as principled rather than profit-driven (despite being exactly that).

Nike's calculation proved sophisticated: they predicted boycott outrage from conservative consumers but understood their primary market, young, urban, diverse, would perceive the stance as authentic. The campaign generated $6 billion in brand value according to Apex Marketing, not despite the controversy but because of it. Burned shoes and angry tweets provided free publicity while reinforcing Nike's "rebel" mythology. The company essentially crowdsourced its marketing through outrage, letting opponents amplify their message. Kaepernick's casting proves especially strategic; his activism predated this ad, providing legitimacy, while his unemployment made Nike appear brave for association.

What Makes This Analytical Essay Sample Work

|

Analytical Essay Introduction Examples

Struggling with your intro? Here are 3 strong openings with annotations showing what makes them work.

EXAMPLE 9: Hook with a Striking Fact

In 2019, teenage depression rates reached the highest level ever recorded, with 1 in 5 adolescents experiencing a major depressive episode. [HOOK: Surprising statistic captures attention] Mental health professionals initially attributed this to increased awareness and better diagnosis, suggesting rates hadn't actually risen but were simply better measured. [CONTEXT: Introduces competing explanation] However, the timing of the increase which accelerates sharply after 2010 coincides precisely with smartphone adoption and social media penetration among teens, suggesting these technologies don't just reveal existing depression but actively contribute to it. [THESIS: States specific argument with causal claim]

| Key Takeaway: Hook, Context, Thesis. The statistic grabs attention, context introduces debate, thesis stakes a position. |

EXAMPLE 10: Hook with a Provocative Question

Why do American schools still require students to read "The Great Gatsby" a novel about wealthy white people in the 1920s when student demographics have fundamentally changed? [HOOK: Question challenges assumption] Defenders argue the novel explores timeless themes of aspiration and disillusionment that remain relevant across eras and identities. [CONTEXT: Presents standard justification] Yet this defense misses how the novel's perspective, embedded in class and racial privilege, treats its themes as universal when they're actually specific to a narrow demographic, making continued canonical status less about literary merit and more about institutional inertia. [THESIS: Challenges the defense with specific claim]

| Key Takeaway: Questions work when they challenge something readers accept without thinking. The thesis directly addresses the question raised. |

EXAMPLE 11: Hook with Contrasting Scenarios

A student using AI to generate an essay draft, then revising it heavily, submits work that's technically their own writing. Another student uses AI to check grammar and strengthen vocabulary in an essay they wrote entirely themselves. [HOOK: Sets up parallel scenarios] Most universities would consider the first example plagiarism and the second acceptable use, yet the distinction reveals unclear and inconsistent standards for AI use in academic writing. [CONTEXT: Points out the contradiction] Rather than blanket bans or unregulated use, universities need clear policies that distinguish between AI as a generative tool (creating content) versus an editorial tool (improving existing content), because the current vague prohibitions punish students unevenly while failing to prevent actual academic dishonesty. [THESIS: Proposes specific distinction with practical implications]

| Key Takeaway: Contrasting scenarios highlight contradictions that the thesis then resolves with a clear position. |

DEADLINE TOMORROW?

Our professional essay writing service delivers custom analysis in 6-24 hours. Real writers. Real analysis. Real results.

Struggling to find a topic? Browse our Analytical Essay Topics organized by subject, grade level, and difficulty, each with sample thesis statements.

Downloadable Collection for Analytical Essay

Get more analysis examples plus bonus materials.

Example Analysis Guide: How to study examples for maximum learning.

Annotation Key: What each annotation type means and why.

Seeking expert guidance? Our critical analysis essay guide provides in-depth explanations, examples, and writing techniques.

Ready to Submit Your Best Work?

Our analytical essay experts deliver A-grade analysis with proper citations and zero plagiarism.

- Get your custom essay ASAP

- Original work with zero plagiarism

- Unlimited Revisions

- 24/7 Support

No AI shortcuts. Just expert-level quality.

Get Expert Help NowBottom Line

Strong analysis essay examples share common traits:

- Specific evidence

- Clear interpretation

- Logical organization

- Insightful connections between details

- Larger meanings.

Study these patterns, adapt them to your topic, and focus on developing original insights rather than imitating content. Analysis improves with practice; each essay you write sharpens your ability to see deeper significance in texts, images, and ideas. Whether you're tackling a critical analytical essay or a standard literary analysis, these examples provide the roadmap for success.

Want step-by-step instructions? Return to our complete analytical essay guide for writing process breakdown, technique tutorials, and revision strategies.

-19758.jpg)