Effective essay examples demonstrate key characteristics including authentic voice that sounds like an actual teenager wrote them, specific concrete details that prove claims rather than stating them abstractly, meaningful reflection that goes beyond obvious lessons like "this taught me perseverance," tight focus exploring one story or theme deeply rather than covering many topics superficially, and distinctive personality that makes the applicant memorable among thousands of applications.

According to admissions officers surveyed across 50 selective institutions, memorable essays make readers feel like they know the applicant as a person rather than just understanding their qualifications, with 89% reporting they can recall specific essays weeks after reading them when those essays demonstrate genuine personality and a unique perspective.

Use College Essay Examples Effectively

Before diving into the examples, understand how to learn from these examples to maximize the essay's value.

Do This | Don’t Do This |

Notice how each essay uses specific details | Copy sentences or phrases (that’s plagiarism) |

Pay attention to authentic voice and personality | Try to imitate someone else’s voice |

Study how writers balance storytelling with reflection | Use their topics if they don’t genuinely fit you |

Observe different structural approaches | Think you need a dramatic story like theirs |

Identify what makes each essay memorable | Get discouraged if yours feels different |

Always choose your topic carefully because your whole essay and story will rely on that particular zone. To choose what suits you the most, browse our college application essay topics and make your essay unique.

Topic Selected? Don't know how to proceed?

Tell us what you need, our experts will handle the research, writing, and formatting.

- Original work with zero plagiarism

- Fast turnaround

- Expert writers across all subjects

- Free AI and plagiarism reports

No AI shortcuts. Just expert-level quality.

Order NowExamples of College Application Essays

The following examples cover different prompts of the Common App. If you want to learn more about it, visit our Common App essay guide.

Example 1: Common App Prompt #5 (Personal Growth)

Essay Type: Narrative structure focusing on one experience

Word Count: 649 words

Breaking the Mold

The ceramic bowl exploded in the kiln at 2,247 degrees Fahrenheit.

I'd spent three weeks on that piece, wedging the clay, throwing it on the wheel, trimming the foot, bisque firing, glazing, and finally loading it into the high-fire kiln. I'd checked the temperature curves obsessively. I'd vented properly. I'd done everything right.

And it still exploded, taking my neighbor's vase with it in a spectacular shower of ceramic shrapnel.

Mrs. Chen, my ceramics teacher, found me sitting on the floor of the studio staring at the kiln. "Sometimes," she said, sitting down beside me, "the clay tells you what it wants to be. And sometimes what it wants to be is a lesson."

I wanted to argue. The clay didn't "want" anything; it was clay. But Mrs. Chen had been throwing pots for forty years, so I kept my mouth shut and listened.

"You're a good student," she continued. "You follow the rules. You do the steps in order. You trust the process." She picked up a shard of my bowl. "But ceramics isn't about following rules. It's about listening."

That sounded like the kind of fortune cookie wisdom that adults love and teenagers find meaningless. But over the next few months, I started noticing what she meant.

I'd always approached everything, school, music, sports, like a recipe. Follow the steps. Do it correctly. Get the expected result. When I studied for tests, I memorized exactly what the teacher emphasized. When I practiced piano, I played exactly what the sheet music indicated. When I ran cross country, I followed exactly the training plan Coach gave us.

It worked. I got good grades. I played difficult pieces. I won races.

But my ceramics kept exploding.

Mrs. Chen suggested I try throwing without measuring anything. No ruler, no template, no specific end goal. Just clay and hands and whatever wanted to happen.

My first attempt looked like a drunk octopus had tried pottery. My second wasn't much better. But somewhere around the fifth or sixth piece, something shifted. I stopped asking "what am I supposed to make?" and started asking "what wants to happen here?"

A lump of clay became an asymmetrical vase because the clay was pulling in that direction. A bowl stayed thick-walled because thinning it felt wrong. A sculpture emerged that I hadn't planned, just a response to how the clay moved under my hands.

None of them exploded.

I started applying this to other parts of my life. When I studied chemistry, instead of memorizing procedures, I played with why reactions happened. When I practiced piano, I experimented with phrasing instead of robotically following dynamic markings. When I trained, I listened to my body instead of blindly following the plan.

Sometimes this worked beautifully. Sometimes it didn't. But I stopped exploding that feeling of working so hard on something that suddenly falls apart because I was forcing it into a shape it didn't want to hold.

Last month, I threw a new bowl. I checked temperature curves and vented properly. I'm not an anarchist; the rules still matter. But I also checked how the clay felt, adjusted my timeline when it told me it needed more time, and altered my glazing approach when the standard method felt wrong.

It came out of the kiln perfect. Not Instagram-perfect with mathematical symmetry, but perfect in the way that ceramics can be balanced and whole, and exactly what it was supposed to become.

Mrs. Chen put it on the display shelf in the studio. "That," she said, "is what happens when you stop trying to control everything and start collaborating."

I still follow rules. I still value discipline and process. But now I also know when to listen for what wants to happen instead of forcing what I think should happen. And I know that sometimes the most valuable lessons come from pieces that explode.

| Why This Works Specific details: The exact temperature (2,247°F), the technical ceramics vocabulary, the "drunk octopus" description Clear growth arc: Shows specific transformation from rule-follower to someone who balances structure with flexibility Authentic voice: Sounds like a real teenager, not an adult trying to sound impressive Meaningful reflection: Connects ceramics lesson to broader life application without being heavy-handed Memorable imagery: The exploding bowl becomes a perfect metaphor |

Example 2: Common App Prompt #1 (Identity)

Essay Type: Montage structure connecting multiple experiences

Word Count: 642 words

The Art of Translation

I translate between worlds.

At home, my mother asks me to explain why my younger brother got detention for "talking back" when, from our Korean perspective, he was just being honest and direct. At school, I translate my grandmother's handwritten recipes, no measurements, just "a handful" and "until it looks right," into precise cups and teaspoons for my Foods class. On Saturdays, I translate my best friend's rapid-fire English explanations about why everyone's mad at someone on social media into slower, simpler Korean for my parents, who want to understand American teenage drama.

Translation isn't just Korean to English or English to Korean. It's context to context. Culture to culture. Generation to generation.

Some things translate easily. But most things don't work that way.

There's no single English word that means jeong, that deep emotional bond that develops over time through shared experiences. English speakers might say "affection" or "connection," but those feel too simple, too surface-level. Jeong is what you feel for the friend who brings you soup when you're sick, the teacher who stays after school to help you understand calculus, the grandmother who slips cash into your pocket when your parents aren't looking.

In tenth grade, I realized that I couldn't translate jeong because English-speaking Americans don't have the same concept. They have words for love, friendship, loyalty, and gratitude, but jeong is all of those and something more, something that develops slowly and sits quietly underneath everything else.

That's when I stopped thinking of translation as word-swapping and started thinking of it as bridge-building.

When my mom asks why Americans think it's rude to ask someone's age but perfectly fine to ask what they do for a living, I don't just translate the question. I built a bridge between two different ways of understanding social hierarchy. In Korea, age determines respect and relationship dynamics. In America, profession does. The same human needs to understand where you fit in a social structure different organizing principle.

When my economics teacher asks why my parents are so focused on saving money even though our family is financially stable, I build a bridge between the American value of "enjoying life now" and the Korean memory of poverty, war, and unstable times. My parents grew up in Korea during the IMF crisis. My teacher grew up in suburban Connecticut during the dot-com boom. The same human desire for security in different historical contexts.

Building bridges is harder than swapping words. It requires understanding not just two languages, but two complete systems of logic, values, and assumptions. It means standing in the middle, holding both sides in my head simultaneously, finding the commonalities that let people understand each other even when they're starting from different places.

Sometimes people ask if living between two cultures feels lonely, like I don't fully belong in either world. That's probably true in some ways. I'm too American for my cousins in Seoul and too Korean for some of my classmates here.

But mostly, I don't feel lonely. I feel useful.

The world needs people who can build bridges. Between cultures, yes, but also between perspectives, disciplines, and generations. We need people who can understand multiple systems simultaneously, who can translate not just words but entire ways of seeing the world.

I'm not sure yet exactly what I'll do with this skill. Maybe diplomacy, maybe education, maybe something that doesn't exist yet. But I know that whatever I do, translation will be part of it, finding the connections that help people understand each other, building bridges across gaps that feel uncrossable.

Because that's what translation really is: not replacing one word with another, but helping two worlds understand each other.

| Why This Works Unique perspective: Doesn't just describe being Korean-American; explores the intellectual work of cultural translation Concrete examples: Specific translations and situations make abstract concepts tangible Sophisticated thinking: Shows genuine intellectual curiosity and analysis Thematic cohesion: Every paragraph connects back to the central translation metaphor Forward-looking: Connects identity to future goals naturally |

Example 3: Common App Prompt #2 (Challenge)

Essay Type: Narrative structure with Rogerian approach

Word Count: 638 words

The Debate I Lost

I've won eleven debate tournaments. I have trophies and certificates and a shelf full of evidence that I'm good at arguing.

But the most important debate I ever had, I lost completely.

My grandmother lives with us. She's 83, speaks minimal English, and has strong opinions about everything from acceptable dinner times (6 PM, no later) to proper studying posture (back straight, both feet on the floor). When I started staying up past midnight working on applications and projects, she started leaving notes in Korean on my desk: "Sleep is also studying. Tired brain learns nothing."

I ignored the notes. I had too much to do. With college applications, AP classes, robotics team competitions, and volunteer commitments, I didn't have time to sleep eight hours. Successful people slept five hours and thrived. That's what I read in entrepreneur blogs and productivity Reddit threads.

One night around 2 AM, my grandmother came into my room. Not to scold me to stay with me. She pulled up a chair, wrapped herself in a blanket, and sat there.

"Halmoni, you don't need to stay up," I said in Korean. "I'm fine."

"If you stay awake, I stay awake."

I tried logic: "That doesn't make sense. You being tired doesn't help me finish my homework."

She didn't argue. She just sat there, looking increasingly exhausted, stubbornly matching my wakefulness hour for hour.

By 4 AM, I gave up. "Fine. I'll sleep. You win."

"Not winning," she said. "Just loving."

For weeks, I resented her interference. She didn't understand modern academic pressure. She grew up in Korea in the 1950s when life was different. She didn't get that my generation needed to work harder than hers did to succeed.

Then I got sick. Really sick, the kind where you miss a week of school and can barely think straight. When I went back, I'd missed two tests, fallen behind in three classes, and dropped in robotics team rankings.

But something strange happened. After I caught up on sleep and recovered, I learned the material I'd missed in about half the time it would have taken me before. My robotics code, which had been buggy and frustrating for weeks, suddenly made sense. I solved problems in minutes that had stumped me for hours.

Turns out, my grandmother was right. Tired brains learn nothing.

I started researching sleep deprivation. Actual scientific research, not entrepreneur blogs. Memory consolidation happens during sleep. Problem-solving improves with rest. Chronic sleep deprivation impairs cognitive function as much as being legally drunk.

Everything I thought I knew about productivity was backwards. I wasn't succeeding despite sleeping five hours; I was handicapping myself.

Now I sleep seven to eight hours most nights. Sometimes I still stay up late for legitimate deadlines, but I don't make it a lifestyle anymore. And here's the uncomfortable truth: I'm more productive now than when I was "hustling."

My grades improved. My robotics code works better. I actually remember what I study instead of memorizing it temporarily and forgetting it by the test.

But the bigger change is how I think about disagreement. Before, when someone challenged my approach, I built arguments to defend my position. I won debates by overwhelming opponents with evidence and logic.

My grandmother never tried to win a debate. She just demonstrated love through stubborn presence, letting her exhaustion next to my exhaustion prove her point more effectively than any argument could.

I still love debate. I still believe in logic and evidence. But I've learned that sometimes the wisest response to being challenged isn't building a counterargument, it's genuinely reconsidering whether I might be wrong.

The debate I lost changed me more than all the debates I won.

| Why This Works Unexpected angle: Most challenge essays focus on overcoming external obstacles; this explores internal stubbornness Authentic vulnerability: Admits being wrong and resisting good advice Cultural specificity: The grandmother's Korean approach adds uniqueness Real growth: Shows concrete behavior change, not just abstract "learning." Honest voice: Acknowledges discomfort and resentment, making the transformation credible |

Example 4: Common App Prompt #6 (Intellectual Engagement)

Essay Type: Montage structure focused on intellectual curiosity

Word Count: 645 words

Why I Love Broken Things

My phone has been to the emergency room twice. Not for falling in the toilet or cracking the screen during voluntary disassembly.

The first time, I was thirteen and wanted to see if I could replace the battery myself. YouTube made it look easy: heat gun, plastic separator tool, gentle prying, swap battery, done. Two hours later, I'd separated the screen from the housing but couldn't get it back together. Three tiny screws had rolled under the refrigerator. Something that looked important was now detached, and I couldn't remember where it came from.

My dad drove me to the repair shop. The technician looked at my phone spread across the counter like an electronic organ during surgery and asked, "What happened here?"

"Learning," I said.

He charged me $80 to put it back together. My dad was not amused.

The second time, I'd learned about processors and wanted to see Apple's A-series chip. I'd practiced on old phones I bought broken off eBay. I had the right tools, proper technique, and steady hands. This time, I successfully disassembled and reassembled my phone without losing a single component.

My dad found me at the kitchen table, phone in pieces. "Again?"

"I got better at it."

He stood there for a moment, probably calculating the risk-reward ratio of having a daughter who voluntarily breaks her expensive phone for educational purposes. Then he said, "Show me how it works."

I love taking things apart. Not just phones, everything. Broken laptops, dead hard drives, and discarded printers I find at e-waste recycling centers. My closet contains seventeen boxes of salvaged components: logic boards, ribbon cables, tiny screws sorted by size, broken screens that still interest me even though they'll never display anything again.

My friends think it's weird. My mom thinks it's a mess. My physics teacher thinks it's fantastic and gave me permission to use the science lab workbench for disassembly projects.

But here's what they don't understand: broken things are the best teachers.

Working electronics are black boxes. You press buttons, things happen, and you never wonder about the complex systems making it possible. But when something breaks, you have permission to look inside. You get to see how dozens of components work together, how electrical signals become information, how abstract code becomes physical reality.

I learned more about electrical engineering from broken electronics than from any textbook. Textbooks show you clean diagrams with clearly labeled parts. Real circuit boards show you a messy reality: components layered densely, pathways winding around each other, emergency fixes where designers obviously realized mid-production that they'd made a mistake.

Broken things also teach you humility. That first phone disassembly taught me that watching YouTube videos doesn't make you skilled. The second attempt taught me that sometimes you need to fail at something multiple times before you succeed. The third through seventeenth attempts taught me that electronics are both more robust and more fragile than you'd think, able to survive my clumsy early attempts but also capable of dying from one misplaced screwdriver slip.

Last month, my school's robotics team's controller died two days before the competition. Our mentors said we'd need to order a replacement and withdraw from the event. I asked if I could try fixing it first.

They were skeptical. I'd broken my own phone repeatedly. Did they really want me touching crucial competition equipment?

But broken things are my specialty. I disassembled the controller, found the damaged component (a tiny capacitor knocked loose during transport), soldered in a replacement from my parts boxes, and had it working within three hours.

We took second place at that competition. I didn't score the winning points or make the crucial plays. But I got us there by understanding something most people never think about: broken things aren't useless. They're transparent. They show you their insides and teach you how the world actually works.

I'm not sure yet whether I want to do electrical engineering, computer science, or something else entirely. But I know whatever I do will involve taking things apart, literally or figuratively, to understand how they work, how they break, and how to make them better.

| Why This Works Distinctive hook: The phone emergency room opening immediately intrigues Genuine passion: Obviously authentic, no one fake-writes about loving broken electronics Intellectual curiosity: Shows learning for its own sake, not just for grades Specific examples: From a failed first attempt to competition success shows growth Personality shines through: Quirky, determined, intellectually hungry |

Inspired by These College Application Essay Examples?

Turn inspiration into a standout personal statement with expert guidance:

- Apply proven essay strategies effectively

- Adapt strong examples to your own story

- Maintain an authentic, student-first voice

- Meet even the tightest deadlines

Examples show the way experts help you execute.

Get Started NowExample 5: Common App Prompt #4 (Gratitude)

Essay Type: Narrative structure focusing on one person

Word Count: 641 words

Mrs. Rodriguez's Question

"Why do you think that?" Mrs. Rodriguez asked.

I'd just answered her question about the American Dream in The Great Gatsby. Something about opportunity and hard work leading to success is the standard AP Lit answer.

"Because..." I hesitated. "Because that's what the American Dream is?"

"That's what people say it is," she corrected. "I'm asking what you think it is."

I stared at her, confused. What did it matter what I thought? We were analyzing Fitzgerald's novel, not conducting personal philosophy surveys.

"I don't know," I admitted.

"Then figure it out," she said, moving to the next student.

This was my first class with Mrs. Rodriguez, eleventh grade AP English. I'd heard she was tough but good. What I hadn't expected was that her toughness came from refusing to accept answers I hadn't actually thought through.

Over the next few months, I realized I'd been coasting through school with borrowed thinking. I could identify themes, cite evidence, and construct arguments, but I'd never stopped to ask whether I actually believed what I was writing.

In Mrs. Rodriguez's class, you couldn't coast. When you answered a question, she asked, "Why?" When you explained why, she asked, "But do you actually think that's true?" When you said yes, she asked, "Why?" again.

It was infuriating.

It was also exactly what I needed.

I'd learned to be a good student by figuring out what teachers wanted to hear and saying it. I'd developed sophisticated radar for detecting the "right" answer, the interpretation the teacher hinted at, the argument that matched our class discussions, the safe response that earned easy points.

Mrs. Rodriguez obliterated that strategy. She didn't want to hear her own ideas reflected back at her. She wanted to hear mine. And I didn't have an,y I'd been too busy parroting other people's thoughts to develop my own.

My first essay for her class came back covered in blue ink. Not corrections questions. Next to every paragraph: "Do you believe this?" "What's your evidence for this claim?" "Is this what scholars say, or what you think?"

I rewrote it three times before she accepted it. By the final version, I'd cut half my original argument because I realized I didn't actually believe it and kept the half that reflected my genuine thinking.

That process was brutal, frustrating, and time-consuming changed how I approached everything.

In Physics, instead of memorizing formulas, I started asking whether they made intuitive sense. In History, instead of accepting textbook narratives, I questioned whose perspective was missing. In my own life, instead of automatically agreeing with friends or family, I started examining whether their conclusions matched my actual values.

Mrs. Rodriguez didn't teach me what to think. She taught me that I'm allowed to think at all.

This sounds obvious. But seventeen years of schooling had trained me to believe that learning meant absorbing correct answers, not developing my own ideas. Good students were the ones who best replicated expert thinking, not the ones who questioned whether experts were right.

Mrs. Rodriguez showed me that real intelligence isn't about memorizing what smart people have said. It's about engaging with ideas critically, testing them against reality, and developing your own informed perspectives.

Last week, I went back to visit her. "I've been thinking about your question," I said. "About the American Dream."

"And?"

"I think Fitzgerald was showing how the Dream becomes corrupted when you chase status instead of purpose. It's not about whether hard work leads to success, it's about what you're working toward and why."

She smiled. "Why do you think that?"

I spent twenty minutes explaining my reasoning, not because she disagreed, but because she genuinely wanted to understand my thinking process.

That's the gift she gave me: treating my thoughts as worth exploring, my questions as worth answering, and my intellectual development as more important than teaching me correct interpretations.

I'm grateful I ended up in her class. But I'm more grateful she refused to let me stay comfortable.

| Why This Works Unexpected gratitude focus: Not about someone who helped during hardship, but someone who made things harder in valuable ways Specific teaching philosophy: Shows exactly HOW Mrs. Rodriguez taught differently Intellectual transformation: Concrete examples of changed thinking across multiple subjects Authentic relationship: The visit callback feels genuine, not manufactured Mature reflection: Shows understanding that challenge can be a gift |

College Application Essay Examples PDF

Example 6: "The Quiet Revolution" (Common App Prompt 5)

| Background: This college essay was written by a student admitted to Northwestern University. The writer chose Prompt 5 (accomplishment or event sparking personal growth) to explore how finding her voice transformed her relationship with herself and others. To understand more, you can review our college application essay outlines. |

Example 7: "The Playlist of Home" (Common App Prompt 7)

| Background: Application essay written by a student admitted to Yale University. The writer chose Prompt 7 (any topic) to explore how music shaped their understanding of identity and belonging. |

Example 8: "Sunday Dinner, Three Languages, Zero Personal Space" (Common App Prompt 1)

| Background: This college essay was written by a student admitted to Duke University. The writer chose Prompt 1 (background, identity, or talent) to explore how her chaotic multilingual family dinners shaped her communication style. |

Example 9: "The Unfinished Puzzle" (Common App Prompt 2)

| Background: This college application essay was written by a student admitted to MIT. The writer chose Prompt 2 (learning from obstacles) to explore perfectionism and learning to value process over completion. |

Example 10: "The Bus Stop" (Common App Prompt 5)

| Background: This college essay was written by a student admitted to Vanderbilt University. The writer chose Prompt 5 (personal growth) to explore a mundane daily experience that changed their perspective on community. |

College Application Examples 11-15: Quick Excerpts

Due to space constraints, here are the opening paragraphs from five more successful application essay examples:

Example 11: Robotics Competition Failure (Northwestern)

The robot drove straight into the wall. Not metaphorically. Literally drove into the cinder block wall of the competition arena at full speed, accompanied by a grinding noise that made everyone within twenty feet wince. I was the programmer. The wall-crashing was entirely my fault... |

Example 12: Family Grocery Store (UC Berkeley)

| Every Saturday morning at 6 AM, I stock shelves at my family's Korean grocery store. Not because my parents make me they'd prefer I sleep in and study. But because shelving is when I learn the most about our community... |

Example 13: Mathematics Beauty (MIT)

| Most people think mathematics is about finding the right answers. I think it's about discovering elegant questions... |

Example 14: Immigration Journey (Yale)

| My mother keeps our green cards in a fireproof safe between her passport and my birth certificate. "These papers," she says, "are worth more than everything else we own..." |

Example 15: Theater Tech Crew (Northwestern)

| No one notices the light board operator unless something goes wrong. Which is perfect, because I prefer making other people shine... |

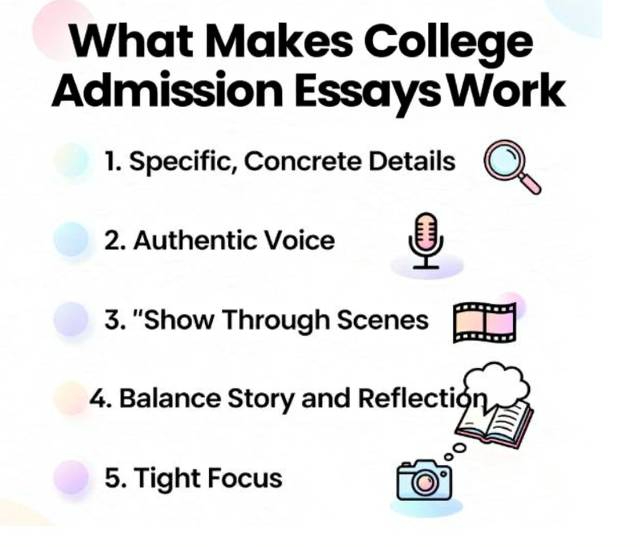

What Makes These College Admission Essay Examples Work: Key Patterns

After reading these college application essay samples, you've probably noticed patterns. Here's what they all share:

1. Specific, Concrete Details

All college essay samples used precise details that couldn't describe anyone else:

- The ceramic bowl exploding at exactly 2,247°F

- The grandmother was sitting stubbornly beside the desk at 4 AM

- The seventeen boxes of salvaged electronic components

- Mrs. Rodriguez's specific question: "Why do you think that?"

Generic details feel forgettable. Specific details feel real.

2. Authentic Voice

These essays sound like real teenagers, not adults trying to sound impressive:

- "That's our job" (not "That is our responsibility")

- "I had too much to do" (not "My schedule was excessively demanding")

- "It was infuriating" (not "This proved quite frustrating")

Write like you talk. Your voice should sound natural, not artificially formal.

3. "Show" Through Scenes

Instead of saying "My grandmother cared about me," the essay shows her sitting stubbornly at 4 AM. Instead of saying "I love learning," the essay shows phone disassembly adventures.

Don't tell readers what to think. Show them scenes that prove your point.

4. Balance Story and Reflection

These essays don't just describe what happened, they explore what it meant:

- The ceramics essay connects to learning when to follow vs. question rules

- The translation essay explores the intellectual work of cultural bridging

- The debate essay examines how stubbornness prevents growth

Events matter less than insights. Always ask: "So what? What does this reveal about me?"

5. Tight Focus

Notice how each essay explores ONE main experience or theme deeply, rather than superficially covering many topics. The MIT phone essay doesn't mention other interests. The Yale translation essay doesn't list other identity aspects.

Depth beats breadth. Always.

Learning from College Essay Examples that worked: Next Steps in Your Writing Process

These college essay examples for students demonstrate different effective approaches to college application essays, but they're meant to inspire your thinking, not constrain your creativity. Your essay should reflect your unique experiences, voice, and perspective, not mimic what worked for someone else.

The key lesson from successful examples is that principles matter more than specific topics or structures. Focus on authenticity, specific details, meaningful reflection, tight focus, and distinctive voice. Apply these principles to your own unique story.

You've seen what successful essays look like. Now what?

For comprehensive guidance on developing your own unique essay that demonstrates these same principles, see our complete college application essay guide covering every phase of the writing process.

Notice how every strong essay uses specific details, authentic voice, and genuine reflection? That's not an accident, that's craft. Our essay writing service specializes in helping students develop these exact skills, working with your real experiences to create essays that admissions officers remember.

If you've already drafted your essay:

- Compare yours to these examples for authenticity and specificity

- Identify where you're "telling" instead of "showing."

- Check whether your voice sounds natural or artificially formal

- Get feedback from trusted readers

- Revise based on what you learned

| Remember: These examples represent final products after weeks of work. Your rough draft won't look like this, and that's completely normal. Follow the process, revise thoroughly, seek feedback, and trust your authentic story. |

Still Unsure How to Write Your Own Essay?

Our professional writers help you move from examples to a polished final draft:

- Personalized topic development

- Clear structure and strong storytelling

- Reflection that admissions officers value

- 100% original, human-written essays

Get support that turns examples into success.

Order NowBottom Line

You've seen 10+ examples of college application essays that worked, from ceramics failures to cultural translation to grandmother wisdom. Now you understand what makes essays compelling: specific details, authentic voice, and genuine reflection. Don't try to copy these stories. Use them to understand effective techniques, then tell YOUR story with the same level of depth and honesty.