What Is a Gap Year and Who Takes One?

A gap year is a structured break of typically 6-12 months between high school graduation and college enrollment, used intentionally for work experience, travel, skill development, volunteer service, or personal growth rather than traditional immediate college attendance.

Gap years differ from simply "not going to college" they're deliberate, planned experiences with defined goals and timelines.

Gap Year Participation Patterns

Gap years remain relatively uncommon in the United States compared to countries like the United Kingdom, Australia, or Israel where they're culturally normalized. Approximately 3-5% of American high school graduates take structured gap years, though this number has grown gradually over the past decade.

Common gap year demographics:

- Students admitted to colleges who request one-year deferrals

- High-achieving students experiencing burnout who need mental health breaks

- Students lacking a clear major or career direction are seeking clarity

- Students need to earn money before college expenses begin

- International travel enthusiasts wanting cultural immersion experiences

- Students pursuing specific opportunities (professional sports, arts, entrepreneurship)

Gap years span a spectrum from highly structured programs (organized volunteer service, language immersion, work exchanges) to independently designed experiences (working full-time, internships, apprenticeships, travel). The structure level significantly impacts outcomes organized programs typically produce more positive results than unstructured "figuring it out" approaches.

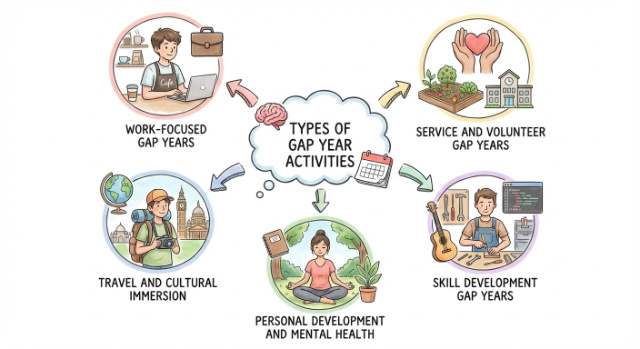

Types of Gap Year Activities

Work-focused gap years: Full-time employment earning money for college, gaining professional experience, or exploring potential career fields. Students may work in retail, hospitality, office jobs, internships, or skilled trades.

Service and volunteer gap years: Organized programs like AmeriCorps, Peace Corps (requires a college degree, but some pre-college programs exist), Habitat for Humanity, or teaching abroad programs. These often provide stipends and college scholarships.

Travel and cultural immersion: International travel combined with language learning, cultural experiences, work exchanges (WWOOF, WorkAway), or volunteer opportunities abroad. Costs vary from budget backpacking to expensive organized programs.

Skill development gap years: Learning specific skills through trade schools, coding bootcamps, art intensives, music programs, or entrepreneurship ventures. These may generate income or require investment.

Personal development and mental health: Taking time to address burnout, mental health challenges, or develop maturity and independence before college's demands. May include therapy, part-time work, and gradual responsibility building.

Most successful gap years combine elements of working part-time while learning skills, volunteering while traveling, or earning money, then pursuing development opportunities.

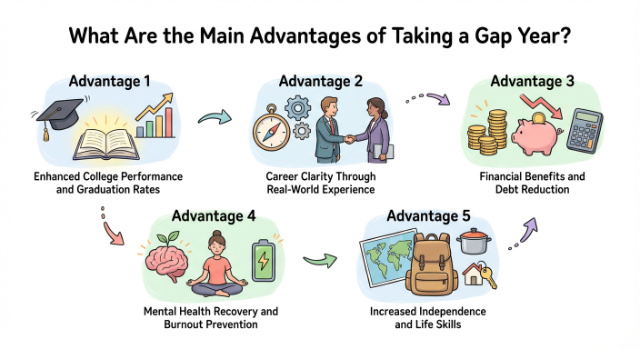

What Are the Main Advantages of Taking a Gap Year?

Gap years offer five primary advantages: increased self-awareness and maturity that improve college performance, practical work experience clarifying career interests, earning money to reduce college debt, avoiding costly major changes by gaining clarity before enrollment, and preventing burnout that leads to dropping out.

These benefits materialize when gap years involve genuine productivity and growth rather than passive unemployment.

Advantage 1: Enhanced College Performance and Graduation Rates

Students returning from structured gap years often demonstrate stronger academic performance and higher completion rates. The maturity gained from real-world experience, combined with renewed motivation from time away from academic pressure, creates more focused students who maximize educational opportunities.

Research tracking gap year students suggests they typically earn GPAs approximately 0.1-0.4 points higher than their pre-gap-year academic predictions would suggest. The improvement appears strongest for students who were academically capable but lacked motivation or direction during high school.

Why gap years improve college performance:

- Real-world perspective increases appreciation for educational opportunities

- Time away from academic pressure reduces burnout and restores motivation

- Work experience clarifies career goals, making coursework more purposeful

- Increased maturity improves time management and self-regulation

- Life skills from independent living transfer to college success

Students who take gap years also show moderately higher four-year graduation rates compared to peers with similar high school profiles. The clarity and motivation gained during gap years help students persist through challenges that cause less-focused students to withdraw.

Advantage 2: Career Clarity Through Real-World Experience

Many students enter college uncertain about their major, leading to costly changes that extend graduation timelines. Gap year work experience provides practical exposure to careers, helping students make informed decisions before investing tuition dollars.

Working full-time reveals preferences you can't discover through academics alone. You might love studying psychology, but realize you hate clinical work after shadowing therapists. You might discover unexpected passion for trades, business, or technology through jobs you'd never considered.

Career exploration benefits:

- Test interest areas before committing to expensive degree programs

- Discover unexpected talents or interests through diverse work

- Build professional networks in potential career fields

- Understand workplace realities versus academic theoretical study

- Make informed major selections based on actual experience

This clarity prevents the expensive pattern where students change majors multiple times, adding semesters or years to graduation. One gap year, discovering that engineering isn't for you, saves three years and $100,000+ compared to changing majors junior year.

Advantage 3: Financial Benefits and Debt Reduction

Gap years spent working full-time can significantly reduce college debt. Earning $25,000-$40,000 during a gap year allows students to start college with savings rather than immediately borrowing, potentially reducing total debt by $20,000-$50,000 over four years.

Financial advantages:

- Earn $20,000-$40,000 working full-time for 12 months

- Reduce dependency on student loans for living expenses

- Build an emergency fund to prevent crisis-driven borrowing

- Gain financial management skills before handling college budgets

- Some gap year programs (AmeriCorps) provide education awards

Students entering college with $15,000-$30,000 saved can cover books, supplies, and living expenses without loans, keeping total borrowing focused on tuition. This financial cushion also reduces the need for excessive part-time work during college that interferes with academics.

Advantage 4: Mental Health Recovery and Burnout Prevention

High-achieving students often reach college emotionally exhausted from years of intense academic pressure, excessive extracurriculars, and college application stress. Starting college burned out creates risk for academic struggles, mental health crises, or dropping out entirely.

Gap years provide essential recovery time when used appropriately for mental health. Students can engage in therapy, develop coping strategies, build healthy habits, and restore energy before facing college's demands.

Mental health benefits:

- Recovery from academic burnout and chronic stress

- Time to address anxiety, depression, or other challenges before college

- Development of healthy coping mechanisms and self-care practices

- Reduced pressure allows rediscovering interests and motivation

- Prevention of more serious crises during college when support is limited

Importantly, gap years address burnout prevention, not treatment alone. Students with serious mental health conditions should consult professionals about whether gap year timing serves treatment goals or whether immediate college with appropriate support might work better.

Advantage 5: Increased Independence and Life Skills

Living independently, managing finances, handling full-time work responsibilities, and navigating adult challenges during gap years develops maturity that improves college success. Students returning from gap years often report feeling "ahead" of peers in practical life management.

Life skills developed:

- Financial management and budgeting

- Time management and self-direction

- Professional communication and workplace navigation

- Problem-solving in real-world contexts

- Independence from parental support structures

These skills transfer directly to college success. Students who've managed apartments, paid bills, and balanced work responsibilities handle college's independence requirements more effectively than those transitioning directly from structured home environments to dorm life.

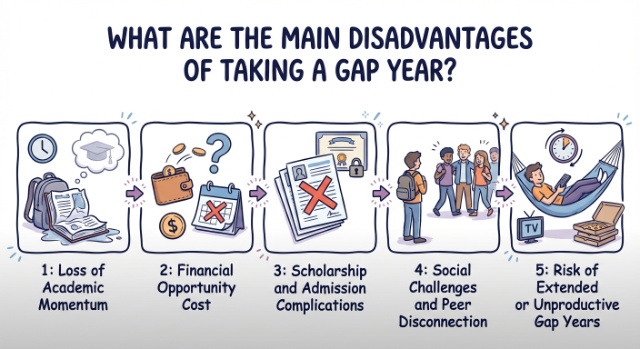

What Are the Main Disadvantages of Taking a Gap Year?

Gap years carry five primary risks: losing academic momentum, making college return difficult, financial costs of delaying high-earning years, potential loss of scholarships or admission offers, social disconnection from peer cohorts, and the risk of gap year extending beyond the planned timeline.

These disadvantages materialize primarily in unstructured gap years without clear plans or accountability.

Disadvantage 1: Loss of Academic Momentum

Twelve months away from studying, test-taking, and academic thinking creates real skill rust. Math abilities decline, writing becomes less sharp, and study habits atrophy. Returning to rigorous college coursework requires readjustment that students entering directly from high school avoid.

Students taking gap years often report that their freshman year feels more difficult than it might have otherwise, particularly in quantitative courses. Calculus proves challenging after a year away from math. Foreign language skills decline without practice. The academic mindset requires rebuilding.

Momentum loss risks:

- Mathematical and analytical skills decline without practice

- Study habits and time management systems need reconstruction

- Academic confidence decreases after an extended non-academic period

- Difficulty adjusting to assignment deadlines and test pressures

- May require remedial courses or struggle initially

This disadvantage affects some students more than others. Highly motivated students regain momentum within weeks. Less disciplined students may struggle for full semesters. The impact also varies by intended major; engineering and science majors face steeper re-entry challenges than humanities students.

Disadvantage 2: Financial Opportunity Cost

While working during gap years earns money, it delays the higher lifetime earnings a college degree enables. Each year delaying college completion postpones professional salary earning by one year, creating opportunity costs potentially exceeding gap year earnings.

Opportunity cost calculation:

- Gap year earnings: $25,000-$35,000 typically

- Delayed professional salary: $50,000-$80,000+ (starting salaries post-degree)

- Net annual opportunity cost: $15,000-$45,000,+ depending on field

- Compounds over career as promotions delayed by one year

For students certain about career paths and academically ready, immediate college attendance maximizes lifetime earnings. Gap years make financial sense primarily when preventing expensive mistakes (wrong major, dropping out) or when mental health issues would sabotage college success anyway.

Disadvantage 3: Scholarship and Admission Complications

Many colleges allow admission deferrals, but scholarship offers sometimes don't transfer. Merit scholarships, particularly, may require enrollment within specific timeframes. Some competitive programs don't permit deferrals, requiring reapplication after a gap year.

Potential financial losses:

- Merit scholarships may not defer, requiring reapplication with no guarantee

- Housing deposits and priority registration benefits may be lost

- Need to reapply to some programs, risking rejection

- Financial aid packages may change between admission and delayed enrollment

Before committing to gap years, confirm your colleges' deferral policies and scholarship portability. Some schools enthusiastically support gap years with guaranteed admission and scholarship protection. Others view deferrals negatively or administratively prohibit them.

When requesting deferrals with compelling gap year plans that maintain admission and scholarship offers, a trusted essay writing service can help you articulate mature, well-reasoned plans that demonstrate intentional growth rather than avoidance, increasing approval likelihood and protecting your financial aid.

Disadvantage 4: Social Challenges and Peer Disconnection

Entering college a year behind friends creates social challenges. Your high school peers start college together, forming freshman year bonds while you're absent. Returning a year later means integrating into a new cohort without existing friendships.

Social complications:

- High school friends move forward without you socially

- Starting college means making friends with students who are a year younger

- FOMO (fear of missing out) while peers experience their freshman year together

- Potential feelings of being "behind" peers academically and socially

- Family and community question about your delayed start

For socially confident students, integrating into new cohorts poses minimal challenge. For students who struggle socially or rely heavily on high school friendships, the disconnection feels more significant. The impact varies dramatically by personality and social skills.

Disadvantage 5: Risk of Extended or Unproductive Gap Years

The most serious gap year risk is that planned single years extend indefinitely. Students enjoying work income or travel experiences repeatedly postpone college. "One year" becomes two, then three. Momentum loss compounds, and college may never materialize.

Gap year extension risks:

- Enjoying work income makes returning to student poverty unappealing

- Travel or experiences feel more rewarding than academic demands

- Lost momentum makes starting college feel increasingly daunting

- Life circumstances change (relationships, employment, family needs)

- A gap year becomes a permanent abandonment of college plans

This risk heightens significantly with unstructured gap years lacking concrete plans, timelines, and accountability. Students with accepted college offers and defined return dates usually matriculate. Students "taking a year off" without formal plans or admission often don't return.

How Do You Decide If a Gap Year Is Right for You?

Decide if a gap year fits your situation by honestly assessing four factors: whether you have concrete productive plans beyond vague "time off," whether you're motivated by avoidance or positive goals, whether your target colleges allow deferrals, and whether delaying college aligns with your financial and career timeline.

Students answering yes to productive plans and positive motivation while having deferral approval typically benefit; those seeking escape without plans often regret delays.

The Gap Year Decision Framework

Question 1: Do you have specific, concrete gap year plans?

Productive gap years require defined activities occupying your time productively. "Figuring things out" or "taking a break" without structure often devolves into extended unemployment, achieving little.

Strong gap year plans include:

- Full-time employment with specific jobs identified

- Organized programs (AmeriCorps, conservation corps, volunteer programs)

- Structured travel with work exchange or volunteer components

- Skill development through formal programs or apprenticeships

- Concrete goals with timelines and accountability

Weak gap year plans:

- Vague "travel" without routes, funding, or activities

- "Working somewhere" without specific job prospects

- "Finding myself" without concrete development activities

- General "break" without a defined purpose or structure

If you can't articulate exactly what you'll do during each month of your gap year, you're not ready to take one successfully.

Question 2: Are you running toward opportunities or away from problems?

Motivation matters enormously. Students taking gap years to pursue exciting opportunities generally succeed. Students fleeing college because they're afraid, unmotivated, or avoiding challenge often struggle.

Positive gap year motivations:

- Accepted into competitive programs (Peace Corps, Americorps)

- Specific career exploration opportunities through internships or jobs

- Passion projects requiring focused time (starting a business, creative work)

- Intentional skill development with clear learning goals

- Addressing mental health proactively with treatment plans

Concerning gap year motivations:

- "I'm just not ready for college," without specific readiness-building plans

- Avoiding challenge or effort without addressing underlying issues

- Hoping problems resolve passively without active work

- Delaying difficult decisions without gaining clarity

- Following friends or romantic partners rather than personal goals

Be honest about motivation. If you're primarily avoiding college rather than pursuing meaningful alternatives, gap years likely won't address underlying issues.

Question 3: Do your target colleges support deferrals?

Research deferral policies before requesting gap years. Some schools enthusiastically approve structured gap year plans. Others rarely or never grant deferrals, requiring reapplication that risks losing admission and scholarships.

Deferral-friendly indicators:

- Formal gap year policy statements on admissions websites

- Simple deferral request processes without excessive requirements

- Scholarship protection during approved deferrals

- Encouragement of gap years in admissions materials

Deferral-resistant indicators:

- No mention of deferrals in policies (often means rarely approved)

- Requires reapplication rather than simple deferral

- Scholarships explicitly non-deferrable

- Competitive programs stating they don't allow delays

If top-choice schools don't support deferrals, gap years become riskier propositions requiring reapplication with no guarantee of readmission or scholarship renewal.

Question 4: How does timing affect your trajectory?

Consider whether delaying college by one year aligns with overall life goals and financial situations. For some students, immediate college makes sense despite potential gap year benefits.

Immediate college may be better if:

- You're academically ready and motivated now

- Significant scholarships don't defer

- You're pursuing time-sensitive opportunities (athletics, prestigious programs)

- Your intended career requires long education (medicine, law), making delays costly

- You lack gap year funding and can't earn enough to justify a delay

Gap year may be better if:

- Burnout threatens college performance and completion

- You're completely uncertain about your major and need exploration

- Mental health issues need addressing before college demands

- Specific, valuable opportunities exist (jobs, programs, experiences)

- Clarity about direction would prevent expensive mistakes

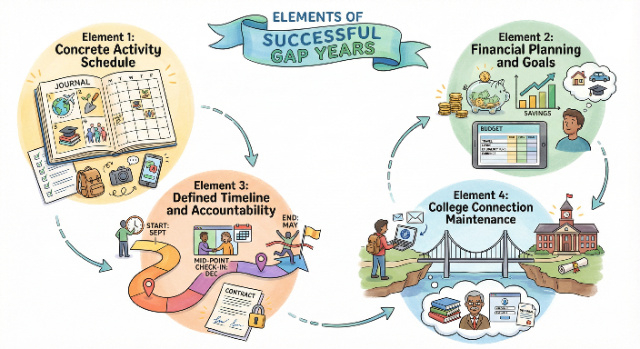

What Makes a Gap Year Successful vs. Unsuccessful?

Successful gap years combine concrete activities addressing specific goals, financial planning covering costs and college savings targets, defined timelines with accountability structures, and maintained college connections ensuring smooth re-entry.

Students who achieve these four elements typically describe gap years as transformative. Those lacking structure often regret the experience.

Elements of Successful Gap Years

Element 1: Concrete Activity Schedule

Successful gap years fill time with purposeful activities rather than vague "exploration." Map out your 12 months week by week.

Sample structured gap year timeline:

- Months 1-6: Full-time employment, saving money, buildinga resume

- Month 7-9: Planned travel with specific destinations and volunteer work

- Months 10-12: Return home, work part-time, take an online course preparing for college coursework, finalize college logistics

This structure balances earning money, gaining experiences, and preparing for college return. Unstructured "see what happens" approaches often disappoint.

Element 2: Financial Planning and Goals

Establish clear financial objectives and track progress. How much will you earn? How much will you save? What expenses will you cover?

Financial planning components:

- Income sources and expected monthly earnings

- Expense budget (housing, food, transportation, activities)

- College savings target ($10,000-$25,000 realistic for full-time work)

- Emergency fund for unexpected costs ($2,000-$5,000)

- Travel or activity budgets, if applicable

Students who work gap years often return with $15,000-$30,000 saved when living frugally at home, substantially reducing college borrowing needs.

Element 3: Defined Timeline and Accountability

Set firm college start dates and maintain accountability, preventing indefinite gap year extensions.

Accountability structures:

- Accepted admission offers with confirmed enrollment dates

- Regular communication with the college admissions office about deferral status

- Family or mentor check-ins about progress and goals

- Written gap year plan reviewed quarterly

- Prepaid college deposits motivating attendance

Without accountability, gap years risk becoming permanent. Formal structures keep you on track toward college return.

Element 4: College Connection Maintenance

Stay connected to college during gap years to ease re-entry. Join social media groups for your class year. Attend admitted student events if possible. Complete housing applications and course registration on schedule.

Students who maintain connections transition into college more smoothly than those who mentally disengage completely during gap years.

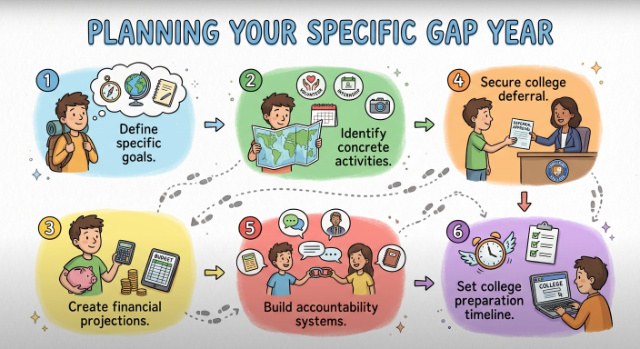

Planning Your Specific Gap Year

If a gap year fits your situation, develop a detailed plan:

Step 1: Define specific goals. What exactly do you want to accomplish? Career clarity? Money saved? Life experiences? Be specific and measurable.

Step 2: Identify concrete activities. What jobs, programs, or experiences will you pursue? Research requirements and application deadlines now.

Step 3: Create financial projections. Calculate expected income, budget expenses, and determine realistic savings targets.

Step 4: Secure college deferral. Contact admissions, understand requirements, and submit compelling deferral requests highlighting structured plans.

Step 5: Build accountability systems. Identify mentors, family members, or programs providing structure and regular check-ins.

Step 6: Set college preparation timeline. Schedule when you'll complete housing applications, financial aid, course registration, and other logistics.

When articulating these detailed plans in deferral requests that determine whether schools approve your gap year and protect your financial aid offers, a reliable essay writing service can help you present mature, well-structured proposals demonstrating the intentional planning that distinguishes approved deferrals from rejected requests.

Gap Year Pros vs. Cons by Student Type

This comparison table outlines how gap year advantages and disadvantages vary based on student profiles, helping you assess whether a gap year aligns with your specific situation.

1. The Burned-Out High Achiever

Students who excelled academically but feel emotionally and mentally exhausted.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Mental recovery and burnout prevention | Risk of losing academic momentum and study habits |

| Renewed motivation for college | May delay entry into competitive programs |

| Time to develop healthy coping strategies | Social disconnection from peers starting college |

| Opportunity to explore interests without pressure | Scholarships may not defer |

2. The Uncertain Explorer

Students are unsure about their major or career path.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Real-world experience clarifies career interests | Gap year may not provide clarity if unstructured |

| Prevents costly major changes later | May extend indefinitely without clear goals |

| Exposure to various industries before committing | Financial opportunity cost of a delayed degree |

| Builds a professional network early | Risk of feeling “behind” peers academically |

3. The Financially Motivated Student

Students need to save money before college.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Significant reduction in student loan debt | Delayed entry into a higher-earning career |

| Develops financial literacy and independence | Some scholarships may be forfeited |

| Gain work experience and references | May be tempted to continue working instead of returning to school |

| Less financial stress during college | Requires strict budgeting and discipline |

4. The Aspiring Professional / Career-Focused Student

Students with clear career goals who want relevant experience.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Builds a resume with relevant internships/work | May delay licensure or advanced degrees (e.g., pre-med, law) |

| Early networking in the chosen field | Competitive programs may not allow deferrals |

| Contextualizes classroom learning with real experience | Opportunity cost of one year of professional salary |

| Potentially secure return offers or references | Risk of industry exposure changing career interests |

5. The Personal Growth Seeker

Students wanting to develop life skills, travel, or gain independence.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Increased maturity and self-reliance | Unstructured travel/exploration can become unfocused |

| Cross-cultural competence and global perspective | Can be expensive without careful planning |

| Improved time management and problem-solving | May lack tangible outcomes for a resume |

| Builds confidence and adaptability | Social challenge of entering college a year later |

6. The Struggling or Unprepared Student

Students who are academically or emotionally unprepared for college.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Time to address academic gaps (e.g., remedial courses) | Risk of not returning to college without structure |

| Opportunity to build study skills and confidence | May reinforce avoidance rather than growth |

| Can work on mental health with professional support | Admission may be forfeited if a deferral is not allowed |

| Prevents potential college failure or dropout | Stigma or family/community pressure |

Key Takeaway

A gap year’s success depends heavily on structure, intention, and self-awareness. Students with clear plans, positive motivations, and supportive college policies tend to benefit most. Those using it as an escape without direction often face the downsides more acutely.

Conclusion

Gap years enhance college success when used intentionally for meaningful work, skill development, or personal growth, but they require concrete plans and accountability to avoid becoming extended unemployment that delays progress without achieving goals.

Key considerations for gap year decisions:

- Take gap years only with specific, concrete plans beyond vague "taking time off" successful gap years involve full-time work, structured programs, meaningful travel, or defined skill development

- Evaluate primary motivations honestly, running toward valuable opportunities typically succeeds, while fleeing college without addressing underlying issues often fails

- Confirm college deferral policies and scholarship portability before committing. Some schools enthusiastically support deferrals, while others require reapplication, risking admission and financial aid loss

- Structured gap years combining work experience and personal development typically boost college performance through increased maturity, career clarity, and renewed motivation

- Main risks include lost academic momentum, scholarship complications, social disconnection, and the potential for one year becoming two or more without strong accountability

Gap years suit students with clear, productive plans, positive motivations toward specific opportunities, and colleges supporting deferrals. They particularly benefit students experiencing burnout, needing career clarity before selecting majors, or wanting work experience and maturity before college's demands. Gap years serve poorly students avoiding challenge without plans to build readiness, those lacking structure, or students attending colleges that don't support deferrals.

If a gap year fits your situation, develop detailed plans including month-by-month activity schedules, financial budgets and savings goals, defined college start dates with accountability, and maintain connections to your college throughout the year.

Students treating gap years as intentional development periods rather than passive "breaks" typically describe the experience as transformative. When you're writing compelling deferral requests articulating mature gap year rationales that maintain admission and scholarship offers, professional essay writing can help you craft strategic narratives demonstrating the intentional planning and clear goals that distinguish approved deferrals from rejected requests.

Download our free Gap Year Planning Template with month-by-month activity planners, financial budgeting worksheets, and college deferral request guidance.